DAHMER | Systemic Failures and the Complexity of Our Zeitgeist

Year

Country

Seasons

Runtime

Original language

Genre

A significant part of contemporary television seriality provides a glimpse of how the forms and contents of television narratives today operate in a very specific trend that has to do precisely with what can be identified as the staging of the obscene (in this case, the term is traced back to one of the origins of the word “obscene” proposed by etymological science. That is, as that which is “offstage”).

Art and its fictional universes have always been shown to have an interdependent relationship with reality. From a more sociological perspective, the content of TV series can be observed as a reflective mirror of the Zeitgeist (“the spirit of the time”).

Building on this basic premise, Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story (or just DAHMER) – the first season of Monster, Netflix’s true crime anthology series created by the tight-knit artistic duo of Ryan Murphy and Ian Brennan – can tell us much more than just the real-life events behind one of America’s most heinous serial killers. DAHMER, with the massive wave of debate it has generated, polarizing critics and viewers alike, and with its shocking viewership numbers, provides further evidence not only of how reality and fiction contaminate each other but also of how the true crime genre has become one of the most appreciated and popular today, despite the ethical concerns inherent in such a genre. Finally, the series offers an anthropological perspective on how the psychological processes true crime dramas trigger in viewers are evolving to better reflect the modern world.

- The Milwaukee Cannibal

- Monster and Human: Beyond Binarism

- An Immersive Experience: Silenced

- Whale Cries

- Projection and Exorcism

- There Are No Answers, Only Questions

- More Monsters to Come

The Milwaukee Cannibal

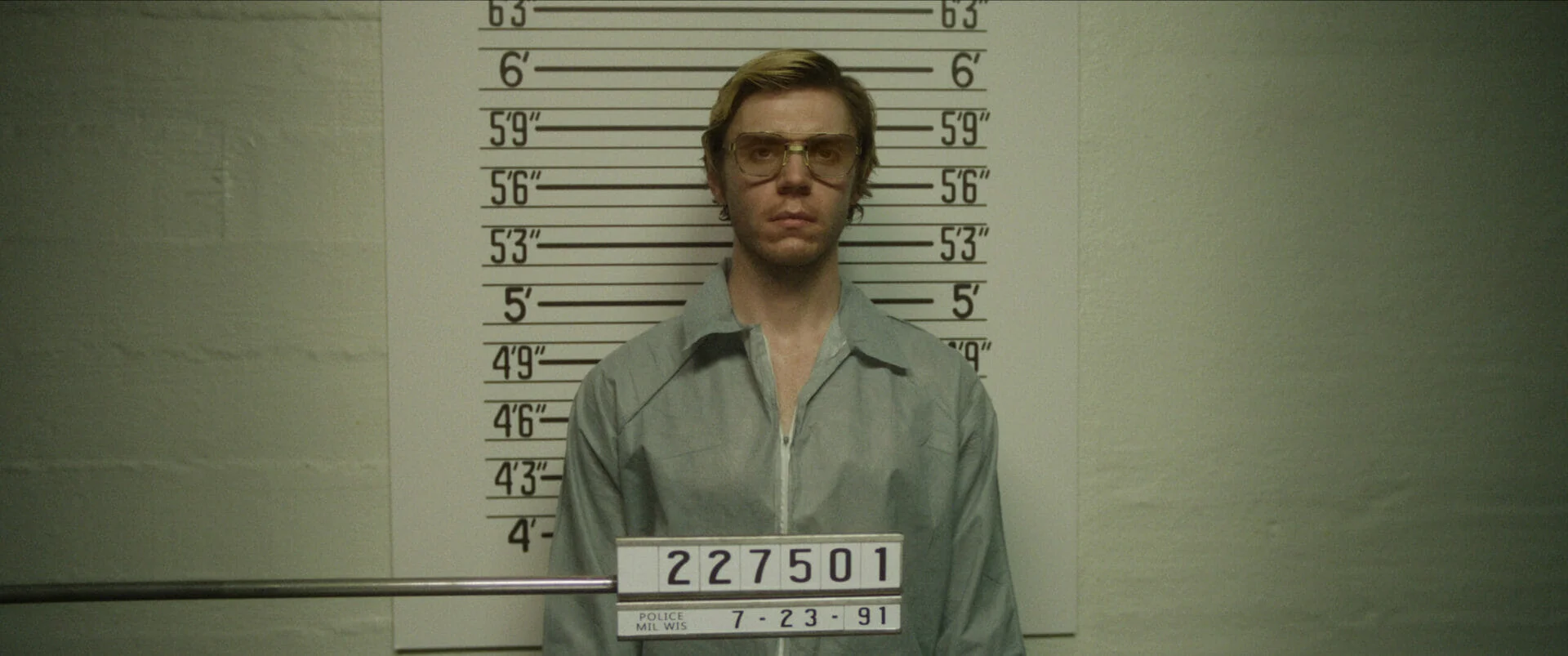

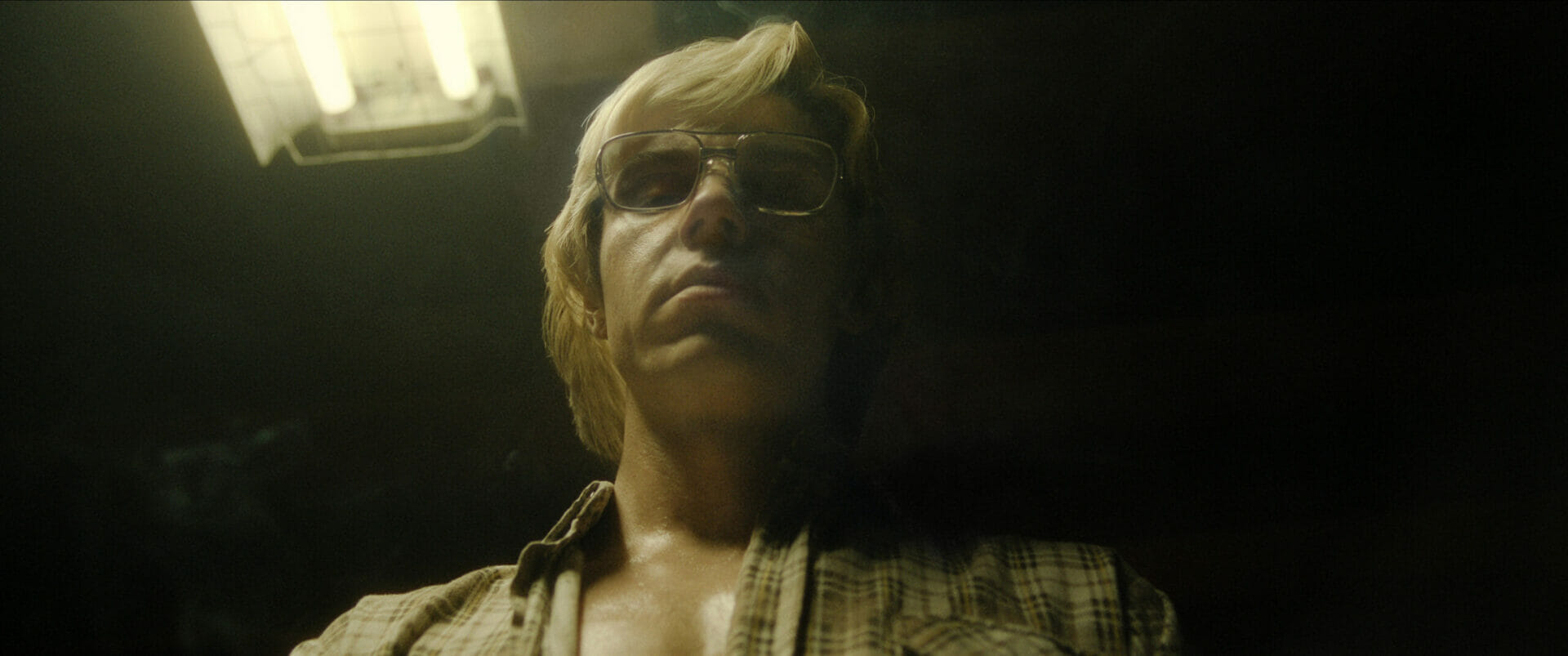

Milwaukee, Wisconsin. DAHMER tells the story of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer (Evan Peters), the Milwaukee Cannibal or the Milwaukee Monster. From his childhood and teenage years with his parents Lionel (Richard Jenkins) and Joyce (Penelope Ann Miller) to his life with his paternal grandmother Catherine (Michael Learned), through the height of his murderous activity while living alone in his apartment with the unanswered pleas of his neighbor Glenda Cleveland (Niecy Nash) for police assistance, to his capture, trial, and death in prison. Between 1978 and 1991, Dahmer brutally murdered seventeen young men. Most of them were black, from various ethnic minority backgrounds, and part of the LGBTQ+ community. His murders included necrophilia, cannibalism, and the concealment and permanent preservation of body parts. He was later sentenced to sixteen life terms and was finally beaten to death by a fellow inmate in 1994.

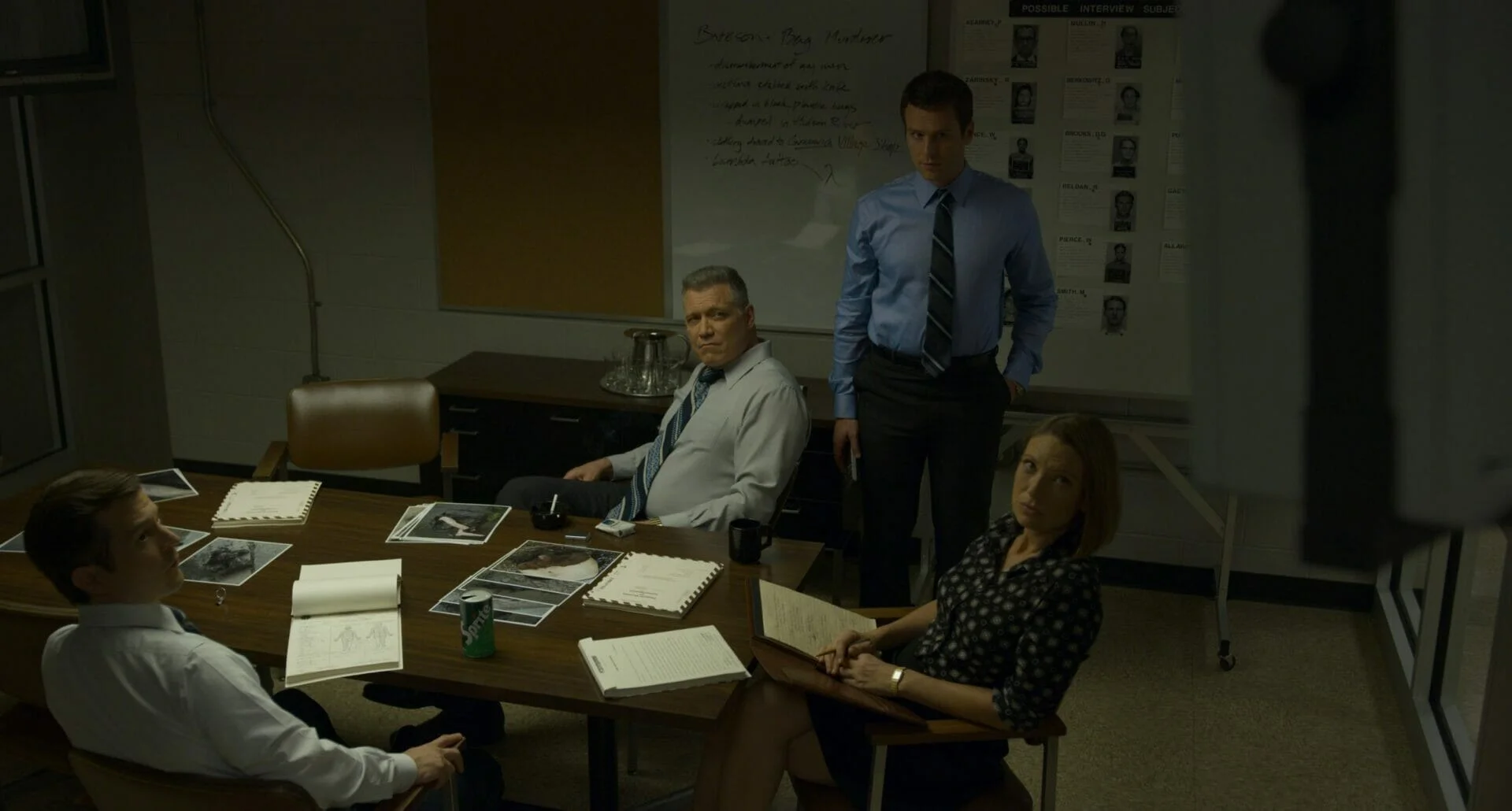

Siding with the victims throughout the narrative and always centering their stories, the show seeks to shed light on institutional police failure, homophobia, and systemic racism as the root causes of Dahmer’s nonchalant and unpunished conduct, which remained in plain sight for more than a decade. But it does not stop there. DAHMER aims to elevate itself and provide a bird’s eye view of what actually happened, taking the time to dig into the harsh reality to reflect and ask analytically and methodically whether it all could have ended differently.

Monster and Human: Beyond Binarism

Babe, I love you so

KC & The Sunshine Band – Please Don’t Go

I want you to know

That I’m gonna miss your love

The minute you walk out that door

So goes the iconic 1979 love ballad by KC and the Sunshine Band. A plea for love and second chances that the show uses in the trailer and in one episode alongside images of Dahmer’s apartment door closing with the victims inside, giving the lyrics new meaning. This is one of many examples of how DAHMER works on multiple levels. It exemplifies how the show strives to reach a deeper level in its storytelling and analysis. Indeed, upon closer examination, one of the most fascinating aspects of the series is its multi-layered structure, precisely because it exploits and plays with the “human/monster” binary system, and then attempts to transcend that same binarism. And it does so right from the choice of title: Monster.

In this sense, DAHMER shows the viewer a portrayal of Jeffrey Dahmer that on the one hand corroborates the term “monster” by distorting and emphasizing actual facts. This happens repeatedly throughout the narrative arc, such as in the scene where a shirtless Dahmer tastes human blood in front of a mirror. Here, the narration seems to want to reassure the viewer by telling them: “You are on the other side: this is a monster. You are not.”

On the other hand, the way the show feeds the viewer Dahmer’s psyche through the dissection of his childhood and relationships seems to push the portrayal toward the term “human”. In this case, by contrast, the narration seems to confess to the viewer: “You are witnessing the story of a man suffering from many ignored diseases – a child with a non-affectionate mother struggling with mental illness. A teenager with an absent father whose only time he was present was when he taught his spongy-minded son to dissect dead animals. An alcoholic adult who has never mastered the codes of relating to others and is always surrounded by a persistent fear of abandonment.”

But there is more. By focusing on exposing systemic racism and homophobia, Jeffrey Dahmer also appears in his other incarnation. A white man, part of a normalized and privileged category, and a gay man, part of an oppressed and marginalized community.

In the end, DAHMER presents an authentic and multifaceted portrait of its main character. But one thing is certain. The series always stays at arm’s length and never succumbs to the glorification or mythologization of Dahmer. If it ever takes the time to examine the wave of fame that washed over him at the time.

It was a challenge to try to have this person who seemingly was so normal but underneath all of it had this entire world that he was keeping secret from everybody. So, you know, we had one rule going into this from Ryan [Murphy] that it would never be told from Dahmer’s point of view. As an audience, you’re not really sympathizing with him. You’re not really getting into his plight. You’re more sort of watching it, you know, from the outside. […] The Jeffrey Dahmer story is so much bigger than just him.

Evan Peters discusses his character with Netflix

An Immersive Experience: Silenced

In the overall series, episode six, “Silenced,” undoubtedly stands out above the others. Written by David McMillan and Janet Mock (Pose, Hollywood) and directed by Paris Barclay, it is an outstanding example of Black storytelling and a vivid demonstration of the use of cinematic language. The episode focuses entirely on the character of Tony Hughes (played by actor Rodney Burford, who is partially deaf and a cochlear implant user), a deaf black man who was murdered by Dahmer in 1991. Not only does this episode strikingly demonstrate DAHMER‘s efforts to keep the victim at the center of the story, but it also cleverly uses the medium to keep Tony and his gaze in the spotlight.

“Silenced” runs largely with no sound or only faint, indistinct background noise. Tony and his family and friends speak in sign language. In addition, in many scenes, the pace slows down to allow Tony to write his thoughts in the tiny notebook he carries to communicate with the other characters (and the public). This allows the viewers to have an immersive and up-close view of the character. They get even closer to his daily life, put themselves in his shoes, and enter his inner world through his lens.

We tried to elevate and we tried to embrace Tony. We tried to give him a voice. We tried as best we could to make him resonate with viewers. And that seemed to have happened. I’m really proud of what we did, not just for Tony, but also for the Deaf community. That was my mantra. We want to make these victims not disappear.

Director Paris Barclay discusses Episode 6 of Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story with Variety.

Whale Cries

The silence gives room to the dark, hellish, sorrowful, and haunting atmosphere provided by the soundtrack composed and performed by Australians Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. Beginning with the eerie “whale cries,” which the show even incorporates into the narrative (Dahmer listens to them in his cell to help him sleep). These peculiar sounds become a veritable leitmotif, guiding Dahmer’s slow walk and almost phlegmatic way of speaking. But also a kind of ritual that musically expresses the attempt to want to descend into the unexplored and dark depths of the human.

Everything seems to take on a labyrinthine, ghostly atmosphere (Oily Tadpoles) filled with anxiety. From the vocals to the piano (New Job, No More Free Rides), to the violin (Death And Baptism), to the synth and flute, everything seems to want to stretch and narrow the hallway leading to the exit of the monster’s apartment. And if the squeezed, claustrophobic, almost breath-choking rhythms of Tourniquet Knot intensify the escape, the slow progress of the End Credits closes the circle and hides the demon underground forever.

Nick and I just sit in a room and start playing. That’s how we’ve always worked historically, whether on film scores or Bad Seeds albums. We create a kind of meditative space where the sound directs the choices made. We improvise a lot – seeking the accidents that happen serendipitously when you place the results with the image. We listen closely to the notes given to us and are happy to take advice on board. The whole team was amazing and professional. Trusting the creatives makes a big difference in the process.

Warren Ellis in an interview with Variety

Projection and Exorcism

“Even in movies, like Star Wars, you know, I always like the bad guys more, you know?”

“Well, so did I. Those characters are written better.”

From the dialog between Jeffrey Dahmer (Evan Peters) and Chaplain Adams (Chris Greene), Episode 10: “God of Forgiveness, God of Vengeance”

The French philosopher and sociologist Edgar Morin, in his seminal 1962 sociological-anthropological essay on the collective imaginary and popular culture, L’esprit du temps. Essai sur la culture de masse (Paris, Grasset-Fasquelle), introduced the concepts of “projection” and “identification”: two psychic transferences that ensure aesthetic participation in imaginary universes.

According to Morin, the imaginary universe comes to life for the viewer, who in turn projects themselves into the characters and/or situations and identifies with them. Through projection, the viewer projects out of themselves, liberating themselves, and exorcising all that lurks in the depths of the self. In this respect, projection can take on the nature of exorcism. To exorcise the evil, the terror, what is harmful and dark in oneself, one’s fears, anxieties, unfulfilled needs, and so on.

Following this thread, and attempting to unravel the tangle that is DAHMER, there is arguably a broader reason for the show’s success. Indeed, when analyzed in this light, DAHMER can be observed as a veritable sounding board for the shadows of contemporary viewers: their inner fears, terrors, and anxieties. Through the series, viewers can exorcise malaise, fear, danger, and anxiety about themselves, their neighbors, and the world we inhabit.

In conclusion, to return to the introduction, the public that DAHMER has attracted in such a short time can be understood as a demonstration of the emergence of a more complex, multifaceted, and even conscious storytelling that allows us to reflect on the present of the Western world and the spirit of our time – and to trigger new processes of identification and projection.

Perhaps, as Jarryd Bartle, researcher, consultant, and associate professor of criminal justice at RMIT University, suggests in an article by Hugh Montgomery for the BBC:

There’s an instinctive morbid curiosity driving people to watch such a show that is timeless. It has been a well-documented feature of humans throughout history. And I do think some of the criticisms that I’ve seen of the Dahmer series are very quick to view that as necessarily a corruptive or bad impulse, but I view it as a natural [one]… I would be more disturbed if there was some kind of moral regime to say ‘people don’t need to know about these things, people don’t need to hear about graphic crimes’. That to me is a more counterproductive social impulse.

Equally, a viewer may condemn a piece of work as unethical, but that may not necessarily stop them watching it all the same – such is the fickle nature of human behaviour.

“Monster: Jeffrey Dahmer: Did TV go too far in 2022?” by Hugh Montgomery – BBC

There Are No Answers, Only Questions

Without a shadow of a doubt, when it comes to true crime dramas, a large segment of the public always prefers to avoid dramatizations of such criminals, leaving their deeds in the past as a sign of dutiful respect. Indeed, since its release, DAHMER has been at the center of many heated debates (including within the crew). Even the families of Dahmer’s victims have reacted, blaming and criticizing Netflix for resurrecting a figure who should have been put aside, capitalizing on the trauma that impacted their lives, and continuing to shine a spotlight on a serial killer who still haunts popular culture today.

I didn’t watch the whole show. I don’t need to watch it. I lived it. I know exactly what happened.

Rita Isbell, sister of Errol Lindsey, one of Jeffrey Dahmer’s victims, discusses the show in an essay published by Insider

Of course, no one is in a position to answer all this pain. And that makes it all the more difficult to discuss and explore an equally controversial series. One thing is certain: DAHMER raises many questions about what we watch and who we are. And for the most part, they are uncomfortable questions. After all, the task of art has always been to raise questions rather than provide answers.

More Monsters to Come

Originally conceived as a limited series, Netflix announced that it has expanded the Monster franchise with two more seasons, making it an anthology series.

At the 80th Golden Globe Awards, Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story received four nominations: Best Limited or Anthology Series, Best Actor for Evan Peters, Best Supporting Actress for Niecy Nash, and Best Supporting Actor for Richard Jenkins.

Evan Peters won the award for Best Actor. During his acceptance speech, he stated: “Last and most importantly, I want to thank everyone out there who watched this show. It was a difficult one to make, a difficult one to watch. But I sincerely hope some good came out of it.”

Tag