1960 European Nations' Cup | When politics defeated football

Event

Length

Winner-Podium

Other protagonists

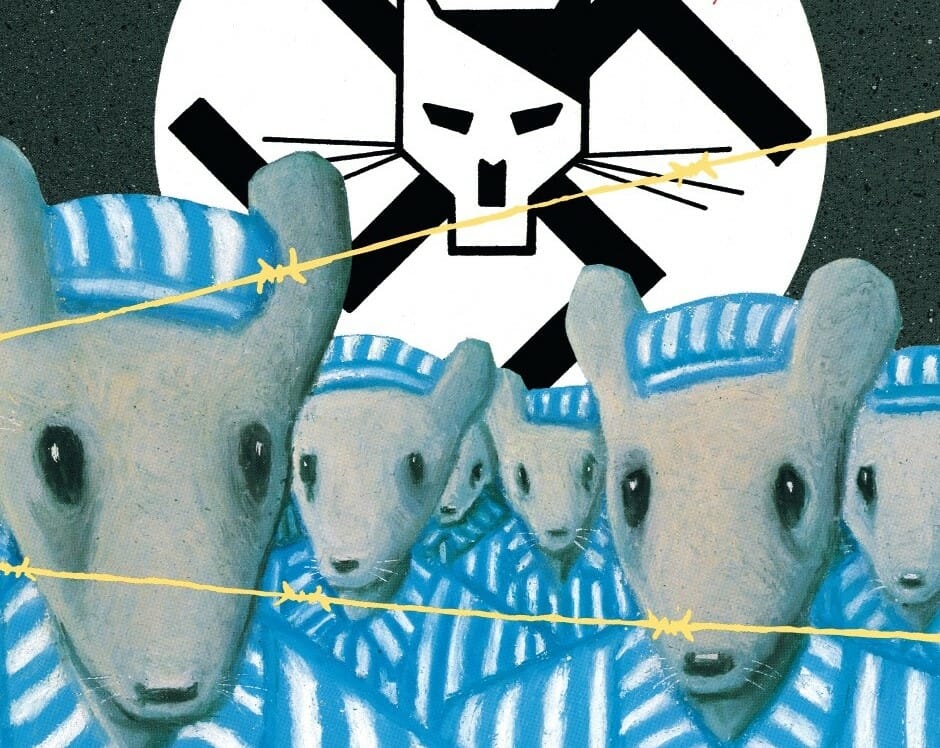

The European Nations’ Cup as we know it today traces its roots back to 1960, while the European International Cup of Nations, its main ancestor, was still underway. More than for being the first edition of the competition, the Cup went down in history for its political implications.

In a period when Eastern Europe was undergoing a certain rapprochement with the West, and Spain was still suffering under Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, UEFA, in the person of Henry Delaunay, put forward the idea of a new and more inclusive competition. The European Nations’ Cup was born, and the Cold War was in the starting lineup and was there to win.

European, but not so much

Even though the competition was intended for more than 30 nations, only 17 teams entered the Cup. England, Scotland, The Netherlands, and West Germany did not want to add new matches to their tight scheduled program in view of the 1962 World Cup. Italy, still smarting from the untimely elimination from the 1958 World Cup and too aware of the inadequacy of its team, wanted to avoid a disaster.

Spain, for its part, decided to participate. Its team worked its way until the quarter-finals and became one of the tournament’s protagonists.

As a result, the first European Nations’ Cup had very little of Europe in it. Moreover, the absence of English, Italian, German and Dutch football did not help hype the event, which was underestimated.

The political round of 16

After a brief preliminary round that led Czechoslovakia to the round of six, the 1960 European Nations’ Cup began. The second round took place between September 1958 and October 1959, when the eight two-legged matches happened.

For the first match of the competition, the USSR and Hungary were to face each other again after the Second World War and the recent Hungarian Uprising of 1956. The Soviet Union got everything: the War, Hungary, and the quarter-finals. Not that Hungary had any chances considering that the referees of the matches were Grill and Kowal, the former Austrian and the latter Polish.

Politics also found room in the goalscorers’ rank, where Francisco Franco‘s favorite Alfredo di Stéfano stood in the first place.

The cold quarter-finals

The eight teams that qualified for the quarter-finals were Austria, Czechoslovakia, France, Yugoslavia, Portugal, Romania, the Soviet Union, and Spain. The absence of many teams had paid off, and Spain was now the favorite for both the qualification and the victory of the Cup. Or, at least, it would have been if politics had not interfered again.

On the eve of the match that would have seen the Soviet Union and Spain on the pitch, Francisco Franco brought the Cold War onto the pitch. The dictator did not want his players to touch Soviet soil and forbade Spain from traveling to the communist URSS. Whatever the Federation did to oppose Franco’s decision was useless. Franco’s measure cost Spain an untimely disqualification and prevented a promising match from happening. Franco had just given the USSR the qualification and the title.

Along with the Soviet Union, France, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia gained access to the next round of the tournament. Three teams out of four got to Paris and Marseille, taking off from Eastern Europe.

The eastern semifinals and final

When Yugoslavia won against France in the first semifinal match, the whole tournament passed into the hands of the Eastern Bloc. Czechoslovakia lost the second semifinal against the Soviet Union but then won the third-place play-off against France. The hosting Nation had to join all the other Western Countries in watching the Eastern podium from below.

The USSR and Yugoslavia were the first-ever finalists of the 1960 European Nations Cup. The match took place on the 10th of July 1960 in Paris, before a not-so-crowded Parc de Princes. Yugoslav strategy and technique seemed to be the winning card when Milan Galić scored the first goal just before the end of the first half, but the USSR’s experience is what made the difference in the end. Right after Galić’s goal, Slava Metreveli balanced the match.

The 1960 Cup ended 113 minutes after the final’s kick-off when Viktor Ponedelnik scored the winning goal and made the Soviet Union the first European Nations Cup winner ever.

The Cup goes to politics

Even though the Soviet Union got the trophy, the actual winner of the 1960 European Nations’ Cup was politics.

Franco, like many other dictators, took advantage of football’s potential and made it an integral part of his doing. The decision to keep the team from traveling to Moscow was a strong message to his most powerful ally, The United States of America, and to the whole Western Bloc. Franco wanted to demonstrate his loyalty, but he also wanted to avoid losing even a football match against the enemy.

Franco changed the destiny of the competition, making it a means to control the world’s political balance. The first European Nations’ Cup was then totally deprived of its original goal: to unite Europe with football.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic