Nero a Metà | A blues roar from the guts of Naples

Artist

Year

Country

Tracks

Runtime

Written by

Produced by

Label

It was September 1945 in Naples. Under the beating southern sun, piles of rubble enveloped the crumbling city center. The war was about to end, and the American troops were soon to leave when a Native American soldier met the eye of a young local girl, Mrs. Musella. Nine months later, she gave birth to a child, Mario.

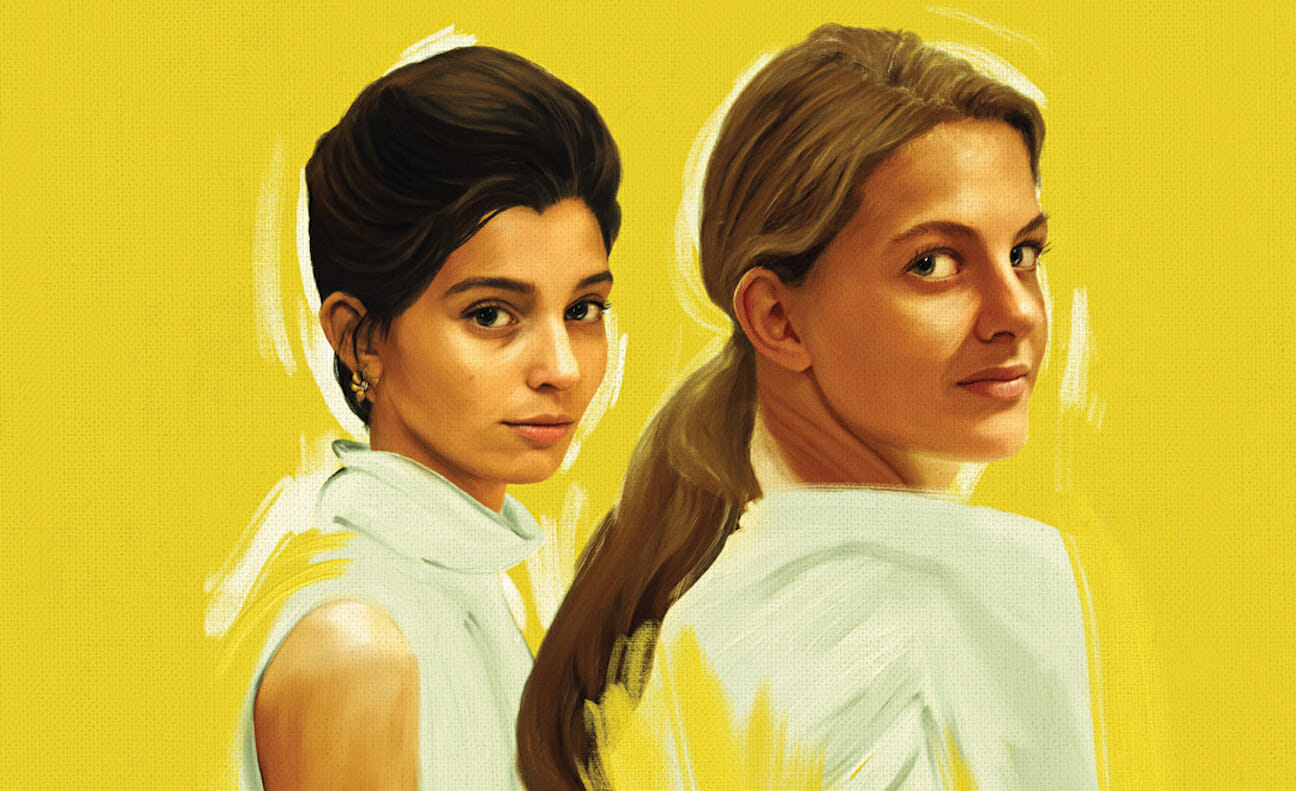

Thirty-four years later, Mario Musella was struck down by liver cirrhosis. He left behind his family, friends, and fans. For the Neapolitan music scene, it was a terrible loss. Yet, Mario was not gone. When young guitarist Pino Daniele heard about his death, he soon realized he had to pay him a tribute, and he ended up making it big. Back in those days, Daniele was working on his third studio album. A guitar virtuoso and blues enthusiast, he was attempting to mesh new rhythmic and harmonic insights with traditional Neapolitan melodies. In part because of Musella’s descent, in part because of his motown-ish sound, Daniele used to call his friend and colleague Nero a metà — half black.

The album came out a year later, and, quite unexpectedly, it became a success. It consecrated Pino Daniele as one of the greatest talents in the country, and established his fame as a Neapolitan bluesman. But Nero a metà is not just an example of musical syncretism. An interpretation of its time, it is the voice of a whole generation.

Neapolitan Power

The seventies were a particularly fertile period for the global musical landscape, and Italy was no exception. Every city had its scene, and every scene became a movement. In Naples, those were the years of the Neapolitan Power. Children of the occupation, like Musella and James Senese, but even younger artists, like Daniele himself, were eager to give a new face to local musical expressions. They listened to Herbie Hancock, Earth Wind and Fire, Chick Corea, but also very traditional artists like Roberto Murolo and Nuova Compagnia di Canto Popolare.

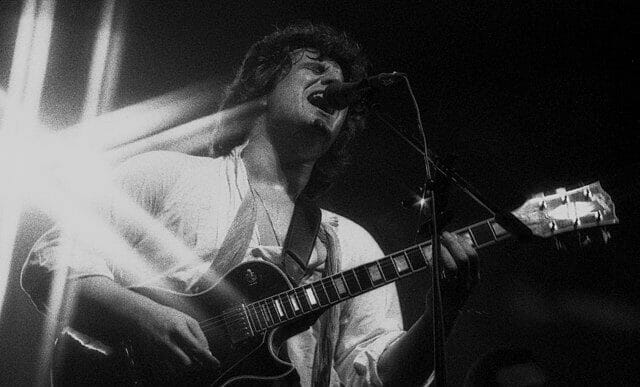

At the age of 25, after two years militating in Senese’s band Napoli Centrale, Daniele was already deeply involved in the scene. Not only did he know all the best musicians in the city: he had their respect, and to produce Nero a Metà, he managed to put together the best of them. Senese played the sax, Agostino Marangolo — a member of The Goblin, who composed Dario Argento’s latest soundtracks — worked on the drums, and Gigi De Rienzo was on bass. It was a super-group, that had a vision. “We had one foot in rock music and one foot in tradition”, Daniele explained. The point was to make their feet dance to a common rhythm.

Shaken by two forces

Nero a Metà features a variety of sounds and styles. The release was promoted by two singles, Nun me scoccià and Quanno chiove. These songs could be described as Daniele’s two musical archetypes. Nun me scoccià is a classic twelve-bar blues with a modern touch: inspired by Peter Frampton, Daniele used a talk box on his guitar for the solos. Yet, the lyrics are deeply rooted in his city’s culture. “Don’t bother me”, he sings in Neapolitan to moralists and intellectuals, “eventually you’ll be dead too”.

The second single, Quanno chiove, strikes a different note. A delicately arpeggiated ballad, it was one of Daniele’s first love songs, and one of the most intimate tracks of the album. The influence of the Neapolitan classical guitar school is evident, and yet Senese’s sax gives the track an unfading ‘70s feel. The choice to release these two songs as singles were not only commercially sensed, it was artistically unavoidable. They perfectly represent Daniele’s two souls, and, ultimately, the whole Neapolitan scene.

September 1945 seemed far away, but something remained the same. Just as thirty years before, Naples was shaken by two forces: the irrepressible veracious-ness of the local character and the relentless advance of a brave new world. And, just as thirty years earlier, it was a beautifully troubled place. In the middle of this all, artists were discovering that the Neapolitan language sounded great on blues and jazz rhythms. And they found out, eventually, that they had something deeper in common with their colleagues from the US.

Music that unchains

“Blues music is, at the end of the day, a rebellion…” Daniele once explained. There was something more to it than a good sound.

“…We can say that there is a relationship between this and us. There is still unfortunately this rivalry, this racism towards southern Italians. It’s there. I know it because I experienced it, and I know that it exists. And this is exactly what needs to be destroyed. The barriers towards these Neapolitans, these «terroni», these louts who continue to be a bit uncivilised, right?”.

Daniele knew what he talked about: the barriers did exist, and he sang so that they might disintegrate. Despite an apparently oceanic distance, it turned out that Neapolitan music and black American music responded to very similar expressive needs.

“A me me piace ′o blues e tutt’e juorne aggio canta′/Pecché so’ stato zitto e mo è ‘o mumento ′e me sfuca′” (I love the blues and I have to sing all day/ because I’ve been quiet and now it’s time to let it out) Daniele roars in A me me piace ‘o blues. This manifesto song is not blues, but funky. A groovy, danceable track, it opens with one of Daniele’s most recognizable riffs. But despite this apparent inconsistency between music and lyrics, Daniele’s message is as strong as his sound. Music is not just a form of art. It is a tool of liberation, and, for Daniele, a means of denouncing the city’s problems.

A whole city’s voice

During the recordings of Nero a metà, no one in the band was aware of the magnitude of what they were doing. As Agostino Marangolo declared years later, “Our principle was to play good music and do something different. We made this album completely unaware that it would become art, that it would make history”. And yet, Nero a metà was destined to become a milestone. Soon after its release, Daniele became a superstar in Italy, and he eventually achieved international recognition. In his long career, he played his songs with artists like Pat Metheny, Chick Corea and Eric Clapton.

But even when he went international, Daniele’s connection to his city never faded, and the mark he left there remains indelible. When he died, in January 2015, 100.000 people gathered in Plebiscito Square to say goodbye to the man who gave them a voice. Pino’s sound was born from the city’s gut, and thanks to his talent it got heard despite all barriers. As he once declared, “The important thing is to be able to maintain one’s own identity and merge it with the language that seems right to us, which in this case stems from the suffering of a people.”

This is, ultimately, the album’s greatest quality. Like his old friend Mario Musella, Pino’s musical soul was parted between two worlds. But in Nero a metà, he made the best of both.

You can stream Nero a metà on Spotify.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic