The Plague | Albert Camus and the Real Disease of the Century

Length

It remains uncertain whether Albert Camus, when he published The Plague with Gallimard in 1947, knew he was sending a message from a not-so-distant past to future readers. He likely did. Epidemics are part of cyclical patterns that have shaped humanity for centuries. The plague in Oran can be seen as seasonal: a disease that emerges, evolves, and returns, like leaves falling in autumn or swallows coming back to their coasts in spring. It is part of the broader history of living beings.

Camus tells the story in dry, unsentimental prose. The invasion of dying rats in the streets of the Algerian city is immediate, in medias res. Early reactions to the first deaths range from private unease to public denial, including institutional hesitation. What follows is crisis management, mistrust, empty streets, mourning, and brief flashes of hope. The Plague functions as a metaphysical allegory. Camus adopts the stance of a clinical observer, tracing how the town responds to the certainty of death.

- The Plague as Chronicle

- The Disease of the Twentieth Century

- Resistance as a Human Response

- Camus Among His Characters

- The Other Face of the The Plague and Camus’ Resilient Humanism

- A City Turned Away from the Sea

- The Sea as a Forbidden Space

- A Moment of Revolt

- When The Plague Came Back

- The Plague as a A Contemporary Allegory

- Separation and Memory

- After the Silence

The Plague as Chronicle

There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise. Dr. Rieux was caught off guard, as were our fellow citizens, and this explains his hesitations. It also explains why he was torn between worry and confidence. When a war breaks out, people say: ‘It’s too stupid, it won’t last.’ And perhaps a war is indeed too stupid, but that doesn’t prevent it from lasting. Stupidity has a knack of getting its way; as we should see if we were not always so much wrapped up in ourselves.

(Albert Camus, The Plague, trans. Stuart Gilbert, 1991, 36-37)

Oran, a French prefecture in Algeria, is a commercial city facing the Mediterranean, yet it also turns its back on it. In the early 1940s, daily life is shattered by a disturbing event: a sudden mass death of rats. This is the harbinger of a bubonic plague epidemic.

After an initial phase of denial by the authorities, the rising deaths and clear contagion force the prefect to act. The city is declared under siege, and its gates are hermetically sealed. Oran becomes a prison of the absurd, a place where “Absurd” means the sudden loss of control over life and the desperate search for meaning in the face of random death and the blind irrationality.

The Disease of the Twentieth Century

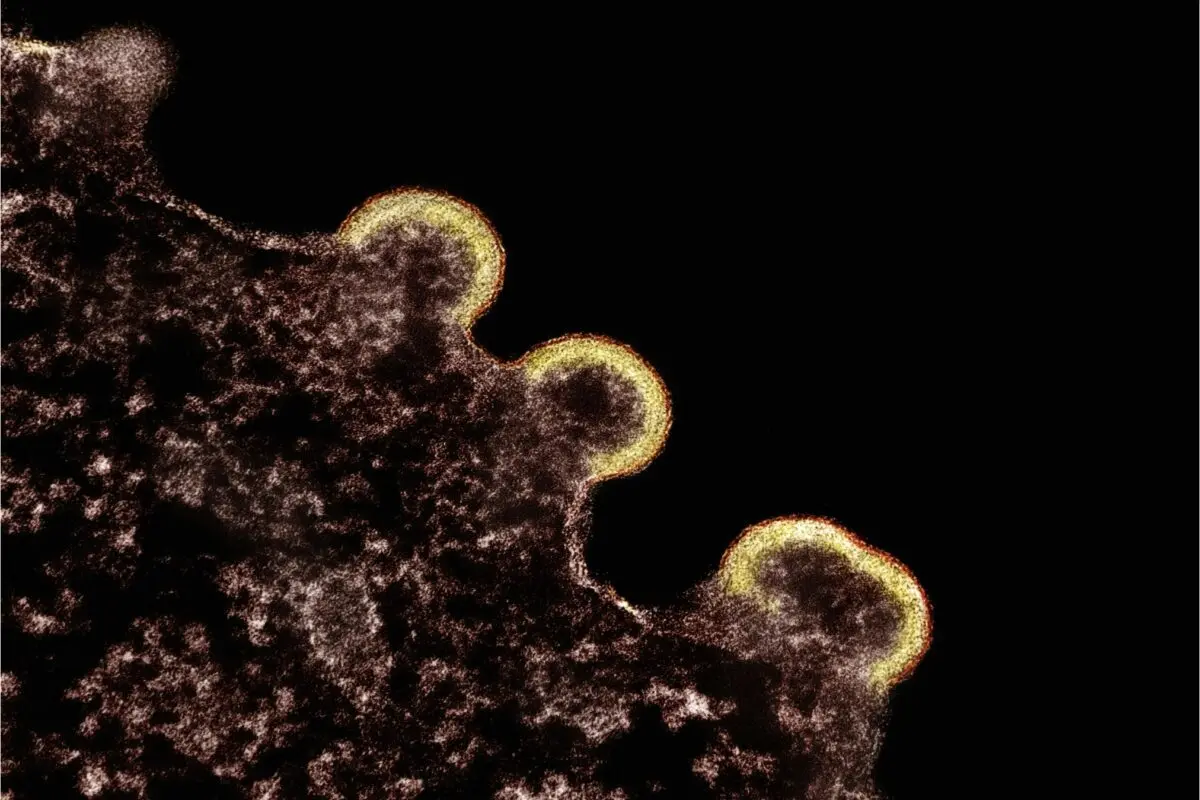

Camus’ The Plague belongs to a precise moment: the mid-20th century, near the end of the Second World War. Back then, the ‘virus’ that had devastated humanity for over twenty years was not biological. It did not originate from rat fleas or parasites – or at least, not in a strictly medical sense. This plague sat in the seats of power: it wore a uniform, spread unscientific ideas of racial purity, deported human beings to labor and extermination camps, and, backed by the bourgeoisie, treated war as a necessary path to progress.

For readers at the time, that virus had just been defeated, though amid rubble and mourning. This is a metaphor that Camus himself was keen to emphasize.

Resistance as a Human Response

It is human resistance in the face of terror that Camus seeks to recount. The Leopardian “social chain” – a deliberate poetic and philosophical reference – re-emerges in the novel through Rieux, Tarrou, and Rambert. They are fragile heroes, determined to confront the epidemic at any cost, as it devastates the community of Oran. Faced with this resistance, Camus moves beyond a purely contemplative stance, telling the story through the eyes of his protagonists.

Although he examines the causes and reactions of a society under a deadly epidemic – whether the indifference to the plague or Hitler’s early actions in Europe – he does not remain detached from the events, quite the opposite. Camus delves into the story, hiding himself among the protagonists, in their personal experiences and moral nuances. In doing so, he takes their side.

The author, after all, lived through the period that inspired the novel’s central metaphor. He spent several years in southern France while it was occupied by Nazi Germany. During that time, Camus, later awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957, came to grasp the ethical value of resistance and solidarity, both rooted in a refusal of violence and oppression.

“What I want is for humans to learn to live and to die, and to refuse death and murder in their hearts.”

(Albert Camus, Actuelles II, Gallimard, 1950, 71)

Camus Among His Characters

The narration, presented as an objective account of events, follows the experiences of a group of characters who embody different moral and philosophical responses to evil. Through their perspectives, readers can glimpse aspects of Camus’ personality, or even fragments of his own life.

The protagonist is Dr. Bernard Rieux, an atheist like Camus and a tireless doctor who fights the plague out of pure human decency:

It’s an idea that may make some people laugh, but the only way to fight the plague is with common decency. […] What that means generally, I don’t know; but in my case, I know that it consists in doing my job. (The Plague, 163)

In the landscape of post-war France, where the nihilist current seemed to express the anxieties of an entire generation, Rieux stood as an exception. As a hero, he opposed the emptiness of the present and the absurdity of history. His goal was only one: to commit himself, as much as possible, to the common good.

Supporting him is Jean Tarrou, an intellectual seeking a form of secular sainthood. He organizes the voluntary sanitary squads and embodies the values of pity, a culture of non-violence, and the refusal to dominate others. Particularly notable is his speech on the choice to be victims rather than scourges:

That is why I decided to take the side of the victims, in every occasion to limit the damage. Among them, I can at least try to discover how one arrives at the third category: in other words, peace.

(The Plague, 253)

Raymond Rambert, a journalist from Paris investigating the treatment of Arabs under French control, initially plans to escape to reunite with the woman he loves. In the end, he chooses to remain in Oran out of solidarity. Rambert is the anti-hero drawn into a moral epic, despite his reluctance.

His choice reflects the surrender of petty-bourgeois individualism in favor of a collective commitment with ethical, and even revolutionary, meaning. Rambert, moreover, is also an exiled journalist, a figure with shades of Albert Camus.

The Other Face of the The Plague and Camus’ Resilient Humanism

Joseph Grand, a municipal clerk, responds to the surrounding chaos by obsessively searching for the perfect opening sentence for his novel. Early in the narrative, he saves a man from a suicide attempt: Cottard. The latter is the only character who derives a concrete benefit from the plague, having avoided arrest for prior crimes because of the epidemic. Furthermore, Cottard sees in the chaos a further opportunity to profit from the shortage of necessities.

However, his trajectory is a clear allegory: Cottard represents the French collaborators of the Vichy government, who chose to prosper in the shadow of the German occupation forces during the Second World War.

Then there is Father Paneloux, the Jesuit who interprets that plague as a form of punitive atonement. The epidemic strengthens faith, calls individuals back to moral responsibilities, while simultaneously protecting them from despair. Paneloux refuses treatment even on his deathbed and never manages to become truly useful to the community. For Camus, the priest represents an unambiguous critique of a certain dogmatic and paralyzing Catholicism.

We cannot speak of a clear dichotomy among the characters. Even Rieux has his abysses, bound by the inconsolable suffering of a distant and ill wife. The same applies to Tarrou, the idealist par excellence, in search of a moral imperative that risks sliding into blind Titanism.

We might interpret these characters in this light, drawing on the words Camus used in Chapter V of The Rebel (L’Homme révolté):

We all carry within us our places of exile, our crimes and our ravages. But our task is not to unleash them on the world; it is to fight them in ourselves and in others. (The Rebel, 306)

A City Turned Away from the Sea

Oran is a city that rises on the coast, built by the sea but turning its back on it.

Our city, it must be confessed, is ugly. […] It is set in a landscape of matchless beauty, in the midst of a bare plateau, surrounded by luminous hills, before a bay of perfect outline. One can only regret that it is built turning its back to the bay and that, therefore, it is impossible to see the sea, which one must always go look for.

Albert Camus chooses a city that is, by definition, a Mediterranean paradox: a commercial community that is nevertheless closed in its habits – claustrophobic, in fact. Even before the epidemic, Oran had chosen to ignore the natural element that defines its geography and suggests its vocation.

In this sense, the plague does not impose imprisonment. Rather, it crystallizes a closure that already existed in the spirit of the city. Thus, when the gates are closed, the horizon vanishes, sinking into a sea of undefined and oppressive spaces. It is no longer a promise of life, the symbolic foundation of Camus’ libertarian humanism – one might think of the “meridian thought” conceptualized in The Rebel and expressed throughout his writings, The Plague included -, but instead it becomes an impassable wall that fuels obsession.

The Sea as a Forbidden Space

Thus, while the city is pervaded by the smell of death, behind it, the sea emanates scents of salt and algae that remind them of lost liberty. For Rambert, the harbor area becomes the border that prevents his escape from Oran. The access to the sea is strictly guarded, and its physical proximity, now that it is unreachable, exacerbates the claustrophobic sensation.

The plague sun extinguished all colors and put to flight all joy. This was one of the great revolutions of the disease. All our fellow citizens habitually welcomed summer with exultation. The city then opened up to the sea and poured its young people onto the beaches. That summer, however, the sea, though near, was inaccessible and the body no longer had the right to its joys.

(The Plague, 111)

This denial, therefore, perverts its meaning. From a symbol of life and connection with the world, the sea becomes an image of death. It is the absurdity that claims and punishes the value of forgotten freedom.

And all through the late summer, as in the midst of autumn rains, one could see passing along the coastal road, in the heart of every night, strange convoys of trams without passengers; swaying high above the sea.

(The Plague, 172)

Many, the narrator recounts, used to throw flowers onto the trams heading toward the sea, hypothesizing that those vehicles were reaching the coast to dump the corpses mowed down by the plague.

[…] groups often managed to slip among the rocks overlooking the sea, and to throw flowers into the cars as the trams passed.

(The Plague, 172)

A Moment of Revolt

Camus, however, cannot and does not fully yield to the absurd. This is why the sea of Oran offers one of the most moving scenes of the entire novel: Rieux and Tarrou’s night swim. It is both a truce and an act of resistance. By stripping off their clothes and plunging into the water, they reclaim the sea. It is the most symbolic expression of the “man in revolt” that Camus could offer.

They undressed. Rieux dived in first. The water, initially cold, seemed tepid when he surfaced. He dived again, swimming steadily. The sea heaved gently at the foot of the large blocks of the jetty, and when they had passed them, it appeared thick like velvet, flexible and smooth like a wild beast. […]

And we read further:

Before them the night was limitless. Rieux, feeling the pockmarked face of the rocks under his fingers, was filled with a strange joy. Turning toward Tarrou, he guessed on his friend’s calm and grave face the same joy, which forgot nothing, not even the murder. […] They dived and swam with more strength. […] For a few minutes they proceeded with the same cadence and the same vigor, solitary, far from the world, finally liberated from the city and the plague.

(The Plague, 256-257)

In this scene, Camus restores the sea to its highest ideals: a homeland between peoples, a place of sharing, migration, and friendship. It embodies the Mediterranean life, or meridian life, that the plague, and even Oran itself before it, had threatened to erase.

When The Plague Came Back

It is 2020, andThe Plague became one of the most purchased, read, and discussed books worldwide. According to Edistat, reported by Le Figaro, sales in France registered an exceptional surge in the first eight weeks of the year: between January and February alone, the Gallimard paperback edition sold 40% of the total volume it usually distributes in a full year.

In Great Britain, Penguin had to reprint the English edition after sales jumped during the last week of February 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.

A similar trend emerged in Italy, where La Repubblica reported that 2020 sales of The Plague, along with Blindness by José Saramago, another suddenly topical novel, tripled on online platforms. Meanwhile, in the United States, the book sparked renewed critical debate, with in-depth essays appearing in The New Yorker, Wall Street Journal, and America Magazine. Academic responses followed as well, including several studies published by Oxford University Press.

The Plague as a A Contemporary Allegory

The cause is easily intelligible, yet that alone would not be sufficient. Many chronicles, dystopias, and treatises on epidemics throughout history could have played a mediating role in that historical moment. Camus’ The Plague, however, offered – even in its immediacy – a more human and solidaristic understanding of the emotions experienced at that time.

Times of quarantine and curfew, daily medical bulletins, and comparisons between infected and deceased – “The only thing left to us is accounting,” Tarrou tells Rieux – were reported in every news edition. The restrictions of social and work places, as well as the militarization of cities, and the consequent warlike language used by politicians and media, were weaponized to face the spread of the virus.

From incredulity to terror, from anguish in the face of prohibition to the desire for a freedom to be reconquered collectively. Reading The Plague, we noticed that during COVID-19, the world was not dissimilar to the events in Oran. In those days, reading Camus meant receiving a plausible answer to that experience lived in real-time, which became, to all intents and purposes, a testimony. Thus, the distance created by the work rapidly collapsed into immediate identification with the narrated events. The Plague played a fully apotropaic role.

Separation and Memory

One of the most striking consequences of the closing of the gates was, in fact, the sudden separation in which people who were not prepared for this found themselves. Mothers and children, spouses, lovers who a few days before had believed they were facing a temporary separation, who had said goodbye on the platforms of our station with two or three recommendations, sure of seeing each other again after a few days or a few weeks, lulled by absurd human confidence, barely distracted by that departure from their habitual worries, saw themselves suddenly inexorably far apart, unable to reunite or communicate.

(The Plague, 68-69)

Reading a passage like this in 2020 was an epiphany. Who, after all, would not have thought during the lockdown about the last moment they had seen someone dear to them? How many were forced to confront the fragility of their own bodies? Fears often arose from even the simplest interactions with others. For some, the lack of respect for public health rules provoked a desperate, almost visceral anger. Most people can find a part of their own experience in these moments.

At the beginning of a pestilence and when it ends, there’s always a propensity for rhetoric. In the first case, habits have not yet been lost; in the second, they’re returning. It is in the thick of a calamity that one gets hardened to the truth – in other words, to silence. Let’s wait.

(The Plague, 36)

As the epidemic advances, silence descends upon Oran. A silence that certainly tastes of death and surrender, but which – in 2020 as in the novel – also expressed a response to a system that was, until that moment, overwhelmed by noise. Oran is a city that feeds exclusively on commerce and has made productivity its raison d’être. The lives of its citizens and their interpersonal relationships are largely driven by profit. In response to its collapse, the silent heroism of the volunteer squad directed by Rieux and Tarrou placed a renewed way of thinking about the human back at the center.

After the Silence

In 2020, too, we experienced once again the silence of which Camus spoke. And in those fragments of emptiness, we dismantled the metaphysics that govern our daily reality, leaving room for imagination. A consequence made possible only at the moment when everything had been denied: only then, as in Oran, did we notice the sea.

The Plague, like COVID-19, has cracked – at least for a moment – the rhythm of a voracious capitalism that allows for no halts, that refuses fear and denies reflection; a devouring force of everything human and nonhuman. By accepting anguish, the sense of being thrown into the world, we, like the citizens of Oran, recognized the foundations for a human revolt.

And if, six years later, the absurd still marches at our gates, just as the scourge of the plague lies dormant, we know that an alternative always exists. An existence to be redeemed day by day. Today, just like six years ago and as in 1947, the lesson of Albert Camus endures.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic