Celebrating 250 Years of the painter William Turner | From Vesuvius in Eruption to the Phlegraean Fields Today

Artist

Year

Material/Technique

Dimensions

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of William Turner, the masterful painter of Light. Born in London on April 23, 1775, Joseph Mallord William Turner was a leading figure of European Romanticism. A young man of precocious talent, he became a member of the Royal Academy of Arts at the age of 14 and exhibited his first work the following year. He began his career portraying evocative architectural views of his homeland, England, before deciding to explore the Old Continent and narrate it through his art. His brush captured dramatic and evocative landscapes, where nature is celebrated in all its wild power. His masterful use of colour made light the central element of his artistic expression.

Turner was able to take the stimuli of nature and translate them onto his canvases, exalting the four elements to the fullest. The power of nature transcends forms, which are increasingly less defined, effectively anticipating Impressionism. The dynamism of his brushstrokes evokes the feeling of wonder and awe that humans experience when confronted with the power of nature. In depicting extreme scenarios, Turner does not limit himself to landscape painting, but explores a more profound sense: that of a living and sometimes threatening nature that challenges our perception of the world and our understanding of safety. A dialogue that today, in light of contemporary environmental vulnerabilities, seems more relevant than ever.

Yale Center for British Art

The painter of the Sublime: between awe and fear

The concept of the sublime was born in ancient Greece as an experience that elevates the soul and generates wonder through the greatness of thought and style. In the 18th century, Neoclassical artists and philosophers redefined the concept of the sublime while renewing historical and artistic interest in classical antiquity.

For the philosopher Edmund Burke, it is that which provokes intense emotion through greatness, darkness, and terror. Kant interpreted it as the clash between the limits of imagination and the infinity conceived by reason. In Romanticism, this idea found expression in the works of Turner and other significant figures of the time, such as Caspar David Friedrich.

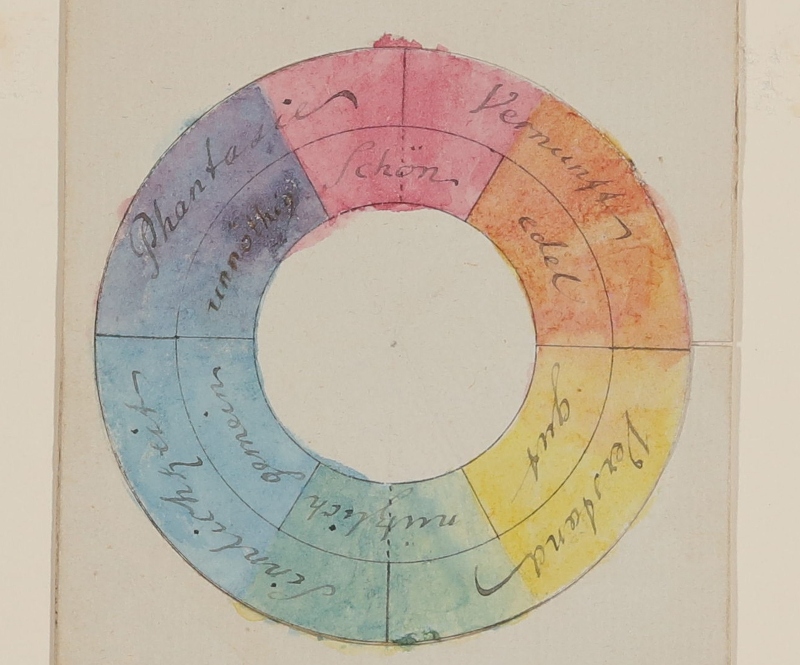

Goethe and color theory: influences on Turner’s palette

If Turner is the artistic emblem of the 19th century, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is his poetic and scientific counterpart. The German author, with his works, dominated and influenced his era and the one that followed, which together define Goethe’s age. What the two such significant personalities of the same historical period have in common is their interest in color. After several trips to Italy, Goethe began experimenting in science with color. In the Belpaese, he was enchanted by the sharpness of landscapes.

In 1810, he published The Theory of Colors, an essay in which he explains his subjectivist view of the color phenomenon. He argues that colors are not objective properties of light, but arise from the comparison of light and darkness. Let it be a smoky glass or a fine fog: when sunlight passes through it, it no longer appears white, but tends to take on a yellow or orange hue. In contrast, if we observe a light source through a bluish shadow, the light appears to us as tending toward blue.

Goethe observes colors as perceptual phenomena, related to human sensibility. For him, color is the product of experience, a dialogue between the eye and the environment. Turner reads Goethe and appropriates his theory through his paintings, becoming almost obsessed with it, and this is evident in the progression of his artistic production, in which light and color are the protagonists. He therefore dedicates one work in particular to Goethean theory, Light and Color – The Morning After the Flood. Moses Writes the Book of Genesis. The painting exhibited at the Tate Britain Museum in London identifies the positivity and warmth of light with the birth of a new world.

Vesuvius in Eruption: Turner’s apotheosis of light and nature

From 1819, Turner visited Italy, an experience that profoundly marked his artistic production. Rome, Venice, Naples, and Florence fascinate him. In Rome, he admires ancient ruins, the colors of Raphael and Titian. In Venice, water and sky become tools for rendering light. Vesuvius in Eruption, painted between 1818 and 1820, is one of the most transparent and palpable externalizations of the concept of the sublime, of Sturm und Drang —storm and rush —of wonder, helplessness, and fear before the power of nature. Turner would visit Naples and see Vesuvius only after composing this painting. He never witnessed an eruptive episode firsthand, although there was some volcanic activity between the 17th and 19th centuries. Therefore, the English painter would have relied on his imagination to convey his vision.

Admiring the watercolor, set in a beautiful, nocturnal Bay of Naples, one notices how the painter’s perspective is above sea level, as if he were admiring the spectacle from a vantage point. The eruption looks more like fireworks, as if celebrating, shedding light into the darkness around. The blue of the night is invaded by the yellow and orange of the fire. A sailing ship can be seen below, intent on returning. There are spectators on the beach, some running away while others stand still watching the scene, motionless, perhaps spellbound or petrified with fear. A spectacle is presented that is as marvelous as it is dangerous.

From Vesuvius to the Phlegraean Fields: perceptions of natural risk today

250 years after Turner’s birth, the evocative power of his works continues to offer food for thought, not only on an aesthetic level, but also on a cultural and social one. Vesuvius in Eruption illustrates how art conveys the sublime and reveals human fragility in the face of nature’s force. In the Neapolitan area, the Phlegraean Fields activity raises questions similar to those that animated the Romantic imagination. How widespread is a fundamental awareness of natural risk? The bradyseism phenomenon recorded in March 2025 has rekindled public attention to one of Europe’s most complex volcanic areas. However, there remains a widespread underestimation of the danger, clouded by a sense of familiarity with the landscape. An aesthetic narrative over time has made Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields almost mythological icons.

Turner depicted the eruption as a sublime event, one that is fascinating in its destructive force. Today, that same aesthetic can contribute to a distorted or attenuated perception of danger. The line between beauty and threat becomes thin, almost invisible. The aesthetics of disaster, so fascinating on canvas, invites us to rethink the landscape as a living, changing, real space. In this sense, Turner’s painting continues to speak with surprising lucidity to the present, reminding us that wonder should never obscure awareness.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic