Ambrogio Lorenzetti | Tradition Meets Modernity from Siena to the National Gallery

Ambrogio Lorenzetti | Tradition Meets Modernity from Siena to the National Gallery

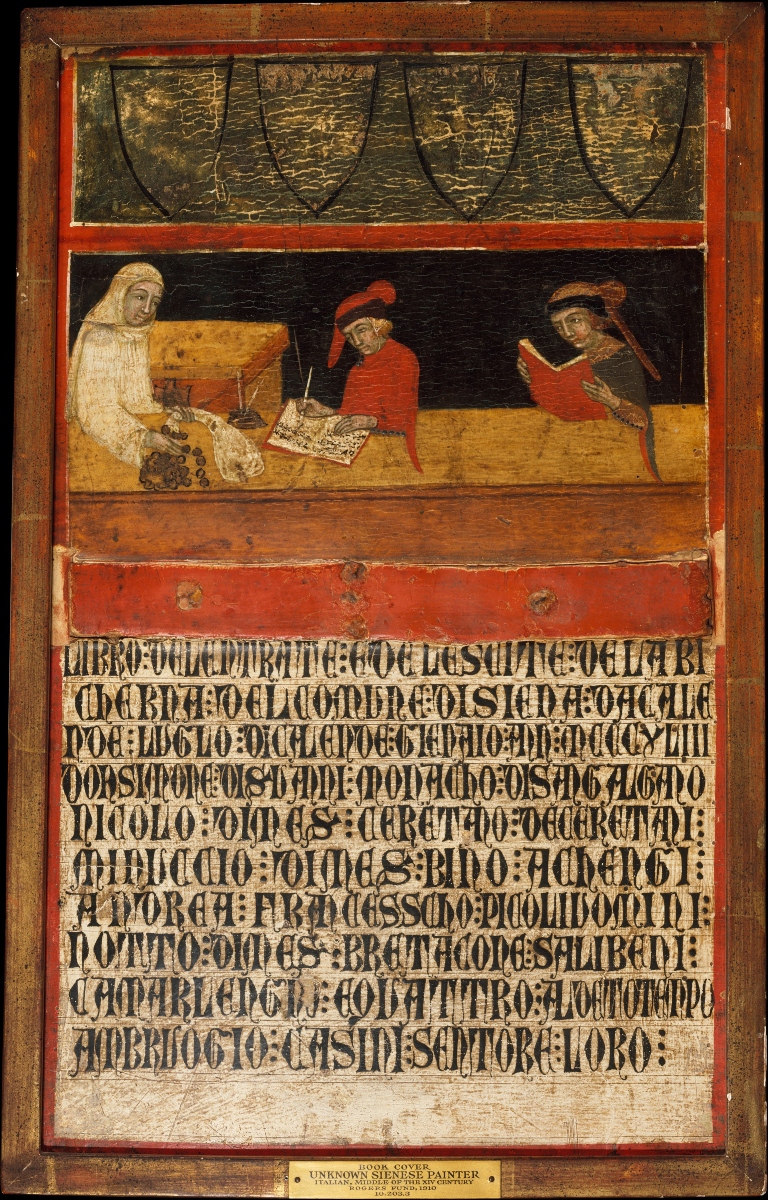

From the late 13th century to the mid-14th century, the city of Siena in Italy experienced its period of most extraordinary splendor. Its political and economic system, governed by the Nine (Governo dei Nove) and its strategic position on the Via Francigena, enabled an unprecedented development phase. From an artistic perspective, Duccio di Buoninsegna revolutionized the Sienese painting scene. With him began what is now known as the Sienese School. Ambrogio Lorenzetti would prove to be a worthy successor.

The exhibition Siena: The Rise of Painting (London, National Gallery, through 22 June 2025) celebrates this pivotal moment in art history. Beginning with Duccio, it examines the works of the key figures of the Sienese School. This golden age, however, was brought to an abrupt end by the fall of the Nine and the plague of 1348.

Before this rupture, the swan song of this extraordinary era was marked by the activity of the brothers Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. The latter, in particular, was the author of the fresco cycle Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government, a true masterpiece of medieval art.

The decline of Siena: the fall of the Government of Nine

By the mid-14th century, Siena’s political and social model entered a severe crisis, culminating in the end of the Government of the Nine and the beginning of a long phase of decline that would ultimately lead to the fall of the Republic. The causes of this downturn were manifold: internal instability, epidemics, most notably the Black Death of 1348, and mounting tensions with neighboring powers.

From the mid-1330s, the political system of the Nine began to show signs of distress. The exclusion of prominent noble families pushed them to engage in violent and destabilizing actions to regain power and assert themselves against rival states. At the same time, artisan guilds and the lower classes, also excluded from city governance, grew increasingly discontented, giving rise to frequent uprisings and revolts.

Epidemics and the Black Death of 1348

Pandemics further worsened the already precarious situation, culminating in the arrival of the Black Death in 1348. This epidemic, made famous by Boccaccio in his Decameron, decimated Siena’s population, losing more than half its inhabitants. As a result, the city was left without agricultural and artisanal labour, and its once-lucrative banking and commercial activities stopped. The expansion of the city’s Cathedral was halted precisely because of the epidemic, as completing the project was no longer necessary or sustainable.

Image generated with AI using OpenAI (DALL·E)

Economic Crisis and Banking Decline

Siena’s financial and banking hegemony also faced a systemic collapse. The outbreak of the Hundred Years’ War (1337) between France and England, Siena’s main banking clients, shook the loan system. Both nations defaulted on their debts, and the Sienese banks were unable to withstand the burden of unpaid loans and the domestic recession brought on by the plague. Furthermore, competition from Genoese, Venetian, and Florentine lenders, who were more adaptable to the shifting political and economic climate, accelerated Siena’s financial downfall.

Florence: Siena’s New Enemy

Florence began to emerge as Siena’s principal enemy. Taking advantage of its rival’s crisis, the Florentines expanded their influence across Tuscany, both territorially and commercially. Florence’s professional militias, more effective than Siena’s condottieri, who were costlier and less reliable, proved decisive. Long wars with the Maremma city-states and powerful Perugia trapped Siena in an expensive conflict with little tangible benefit. The loss of control over the countryside and the forfeiture of agricultural income and maritime trade routes greatly affected the Sienese state.

The End of the Government of the Nine and the Decline of Siena

The Nine’s inability to address these mounting challenges undermined central authority and created a power vacuum. In 1355, taking advantage of his visit to the city, Emperor Charles IV imposed a regime change, favoring the return of the nobility to the top of the state. This marked the beginning of two centuries of unstable governments, regime shifts, and political, economic, and social decay, ultimately leading to Siena’s annexation by Florence in 1555 and the birth of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

The Cycle of the Good and Bad Government: Frescoes with Civic Value

Ambrogio Lorenzetti ensured the everlasting memory of the Government of the Nine. Through his fresco cycle, Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government, the painter offers a unique and extraordinary vision of the spirit of civic rule in Siena, a kind of political manifesto for the city at the time.

Visualizza questo post su Instagram

The rulers commissioned the cycle directly for the very room where they gathered. At the Palazzo Pubblico, the Hall of the Nine was the heart of the city’s government. As a result, the civic value of the frescoes is clear: they were meant to inspire politicians to act rightly, in the interest of all.

Ambrogio completed this masterpiece in just one year: 1338. The cycle unfolds across three walls. On the north wall is the Allegory of Good Government. In it, the figure of the Comune di Siena, wise and regal, is flanked by Justice, Divine Wisdom, Concord, Peace, and the Cardinal Virtues. To govern well, one must be guided by all these virtues.

The east wall illustrates the Effects of Good Government. Here, we see a prosperous Siena, full of bustling shops. Citizens live in peace and dance together. Social life is joyful, and the countryside is fertile and busy. The entire scene is protected by the figure of Security.

Visualizza questo post su Instagram

The west wall depicts the opposite: the Allegory and Effects of Bad Government. Here, Justice is oppressed by a demonic tyrant. War replaces Peace. Siena is in ruins, violence spreads, and the countryside is desolate. Fear dominates, proclaiming the submission of justice to tyranny for self-interest.

In the Effects of Good Government, Lorenzetti captures an image of Siena at its height, thriving under the Government of the Nine, a snapshot of the city before the crisis it would face in the mid-14th century. At the same time, he leaves behind a universal warning: if peace and prosperity are to be achieved, the common good must come before private interest.

Questa santa virtù, là dove regge, induce ad unità li animi molti,

e questi, a cciò ricolti,

un Ben Comun per lor signor si fanno,

lo qual, per governar suo stato, elegge

di non tener giamma’ gli ochi rivolti

da lo splendor de’ volti

de le virtù che ’ntorno a llui si stanno.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti

[paraphrase: This sacred virtue, wherever it prevails, impels many souls to unite;

And these, gathered for this purpose, place themselves at the service of a Common Good as their guide.

This Common Good, to govern its own state, chooses never to look away

from the splendour of the faces of the virtues that surround it].

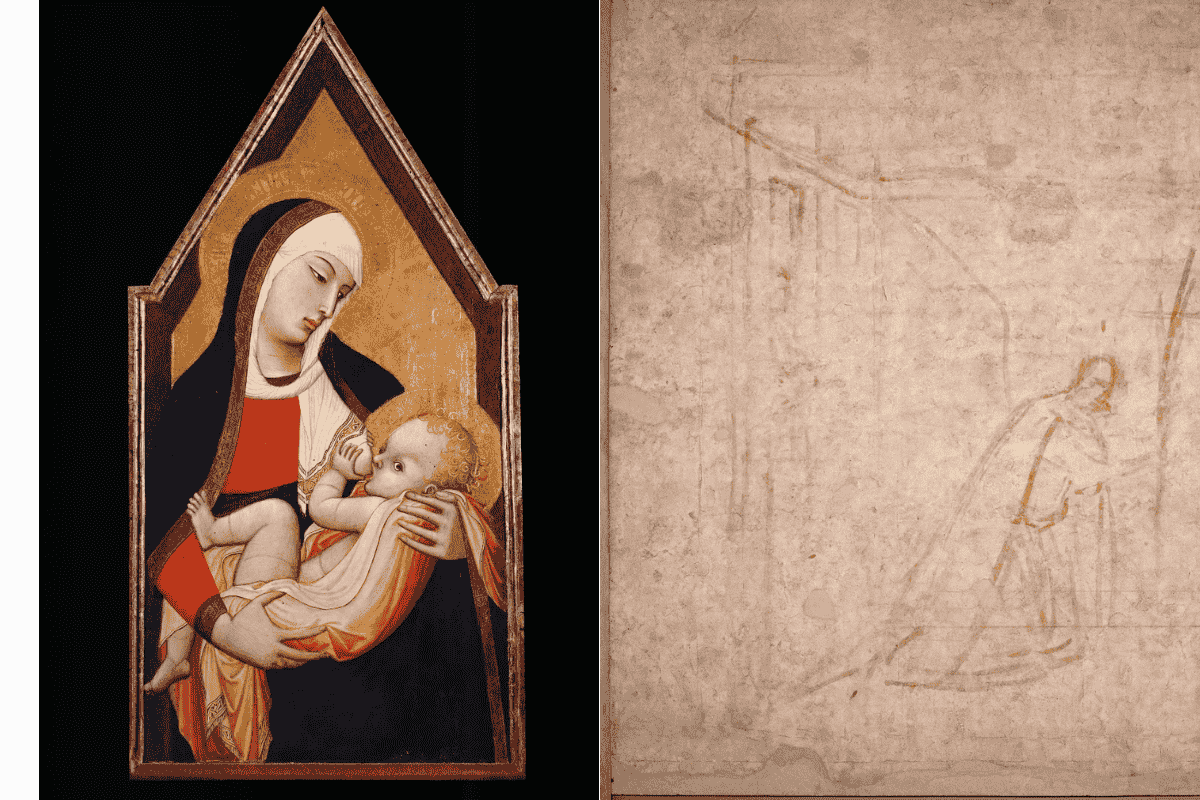

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Nursing Madonna: Humanizing the Sacred

Before the Good and Bad Government cycle, Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s career was already marked by several masterpieces. One of them is the Nursing Madonna. The work depicts Mary tenderly nursing the Christ Child. It belongs to the Diocesan Museum of Siena and is currently on display in London for the exhibition Siena: The Rise of Painting.

This panel is a faithful reworking of a Byzantine icon in a modern key, a traditional model reinterpreted through the visual language of early 14th-century painting. What stands out first is the compositional structure. Contrary to the medieval convention that placed the Madonna rigidly at the center of the image, Ambrogio Lorenzetti shifts her to the left, in a diagonal pose. This revolutionary yet straightforward gesture introduces a new way of conceiving pictorial space. The diagonal of the figure and the golden background that opens behind her create a sense of depth, a visual opening beyond the flatness typical of Byzantine iconography.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Nursing Madonna

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Nursing Madonna, ca. 1325, Siena, Oratory of San Bernardino and Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art.

Image courtesy of The National Gallery, London

Moreover, Mary’s tender gesture as she nurses the Child introduces a degree of humanization and intimacy absent in earlier depictions. The result is a work that, while respecting religious conventions, embraces a new sensitivity, one closer to daily life and emotional connection.

After all, Ambrogio had absorbed the lessons of Duccio di Buoninsegna, the founder of the Sienese School, who brought the innovations of Gothic painting from beyond the Alps into the city.

The Annunciation According to Ambrogio Lorenzetti: A Modern Vision Hidden Beneath the Paint

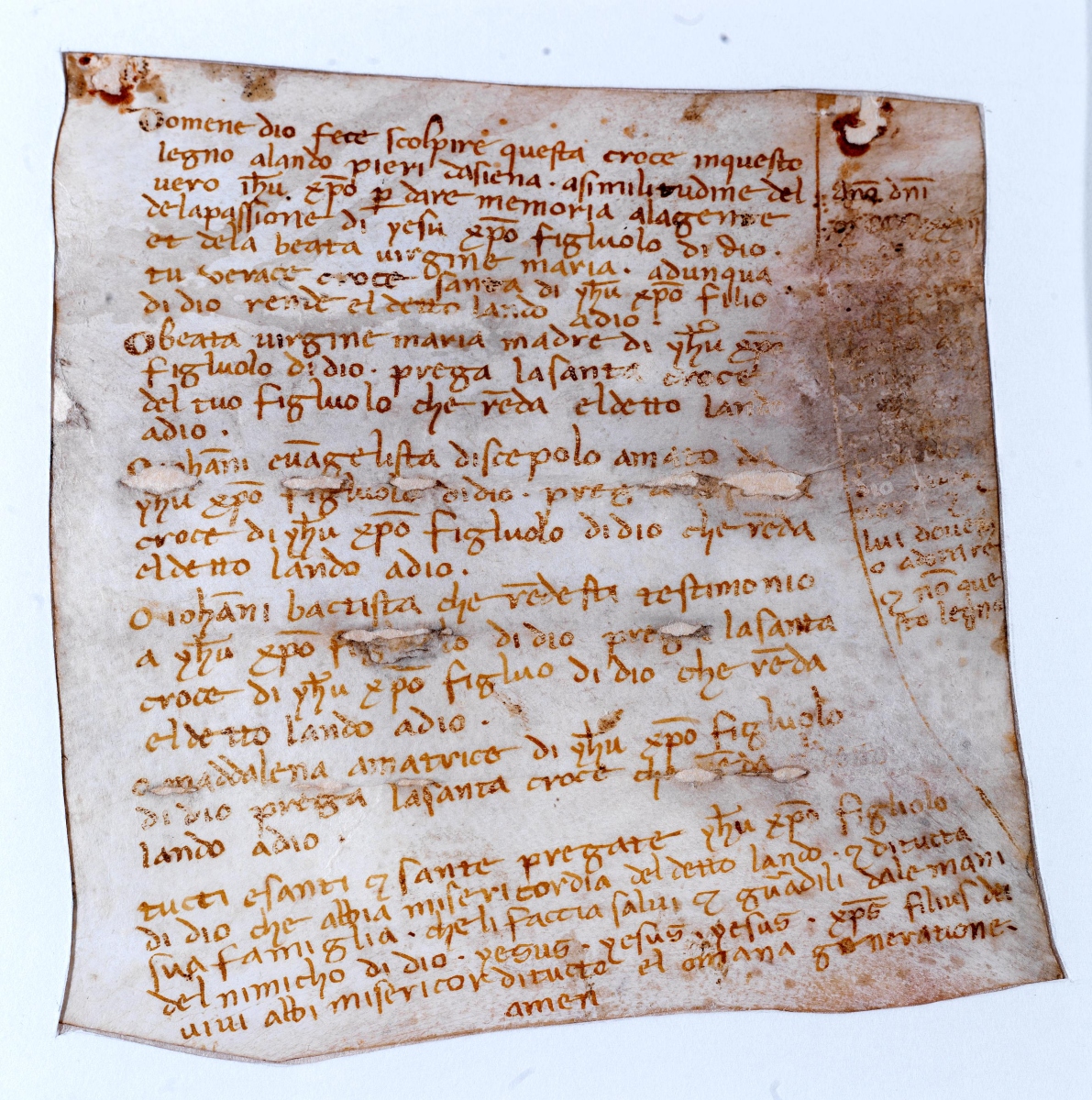

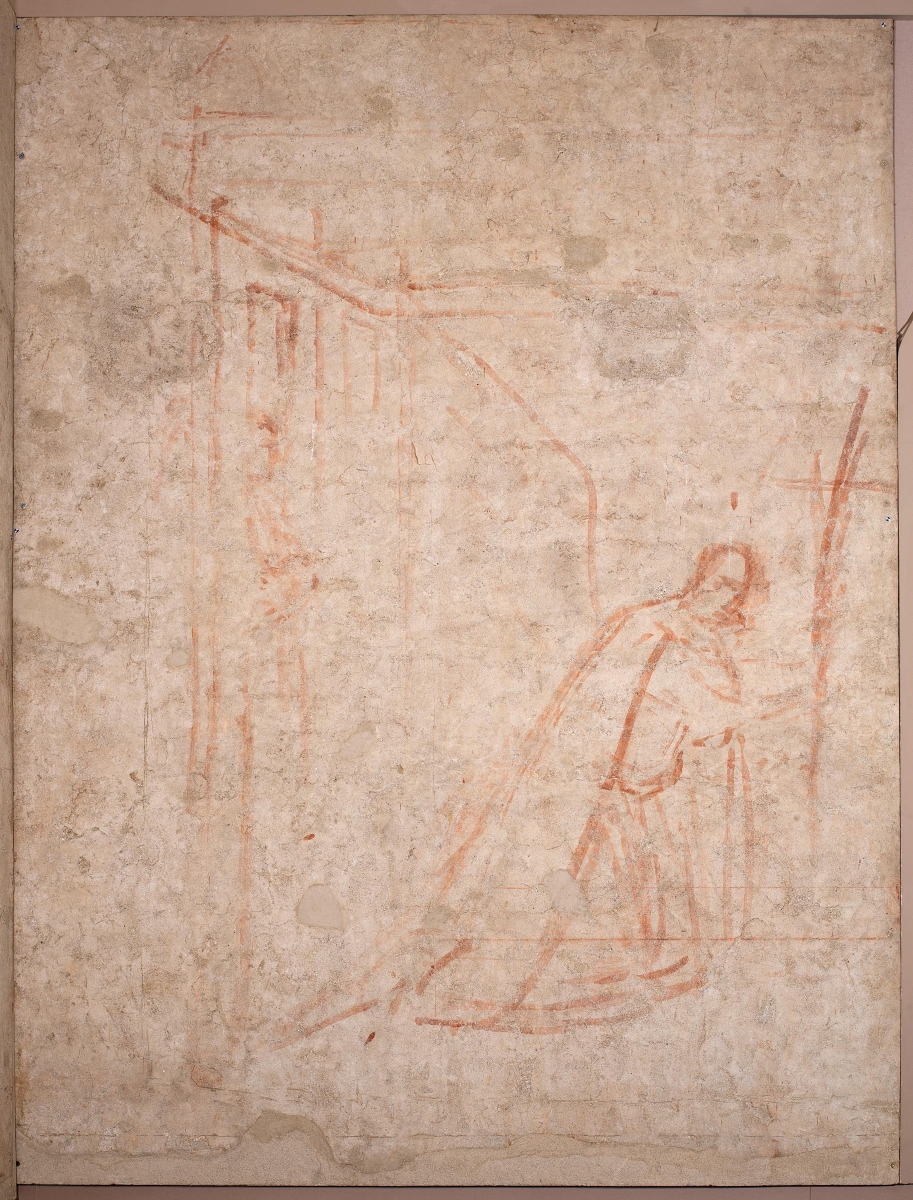

Another major commission Ambrogio Lorenzetti undertook was the fresco cycle for the Hermitage of San Galgano at Montesiepi, a site near Siena where the knight Galgano Guidotti is venerated. Among the scenes requested from the painter was an Annunciation.

As was common practice, Ambrogio Lorenzetti first created a kind of preparatory drawing directly on the wall before painting the final fresco. This underdrawing is known as a sinopia. Sometimes, when frescoes are removed from walls for conservation purposes, this sketch is revealed underneath.

The discovery of the sinopia for the Annunciation, currently on display in London, unveiled a surprise that again testifies to Ambrogio’s modernity. The scene we see is strikingly realistic: the angel glides into the room, and Mary, rather than appearing calm and composed, is visibly shocked. Anyone, in truth, would be frightened in such a situation. And Ambrogio captures precisely the humanity of a woman afraid in the face of the unknown. Mary recoils, throwing herself to the ground and clinging to a column. With just a few brushstrokes, Ambrogio Lorenzetti delivers a moment of unprecedented realism.

The modernity of this sinopia is so remarkable that, in the final version of the fresco, Ambrogio changes his concept entirely, offering a much more canonical Annunciation. Perhaps his contemporaries were not yet ready for such a radical departure.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno: Capturing Movement, Breaking Harmony

A work closer to the Good and Bad Government cycle is this imposing triptych, which remained in its Tuscan context and was not included in the Siena: The Rise of Painting exhibition. It depicts Saint Michael the Archangel defeating a dragon, symbolizing the devil. On the sides, we see the figures of Saint Benedict, in a white habit, and Saint Bartholomew. In the cimase (the upper parts of the polyptych), a tender Madonna holds the Christ Child. On the sides, there are Saint Louis of Toulouse, unfortunately very damaged, and Saint John the Evangelist.

It is not entirely clear who commissioned the work from Ambrogio Lorenzetti. The original location of the triptych is not definitively known, although the splendid Benedictine Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, near Asciano, seems to be a plausible hypothesis.

Triptych of Badia a Rofeno

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno, ca. 1337, Asciano, Museo Civico Archeologico e d'Arte Sacra Palazzo Corboli.

Image courtesy of Fondazione Musei Senesi

The triptych’s name comes from the fact that it was recorded in the Badia a Rofeno, an ancient church near Asciano, in the mid-19th century. Today, it is housed in the Civic Museum of Palazzo Corboli, a medieval palace still rich in 14th-century frescoes and holding some of the masterpieces of the Sienese School.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti once again proves to be a great innovator in this triptych. The central scene is so intense that it contrasts with the calmness of the figures on the sides. Saint Michael fiercely brandishes the sword as he is about to strike the dragon. His fluttering cloak amplifies his gesture, giving it emphasis. The wings frame the scene as if they were a theatrical backdrop.

In the end, Ambrogio Lorenzetti surpassed traditional models through innovative visual direction. The contrast between the central drama and the balance of the figures on the sides not only energizes the narrative but also reveals a conscious spatial and emotional construction that foreshadows fundamental developments in European painting.

Some details from the Triptych of Badia a Rofeno