Proust 100 | A Symphony of memory

One hundred years ago, in 1922, the 18th November was a Saturday. The First World War had ended, and then followed the Spanish flu epidemic that had decimated Europe: photographic evidence has resurfaced from time to time which makes us shudder: people wore masks, as we ourselves wore them during these pandemic years. The Fascist Party had recently taken power in Italy.

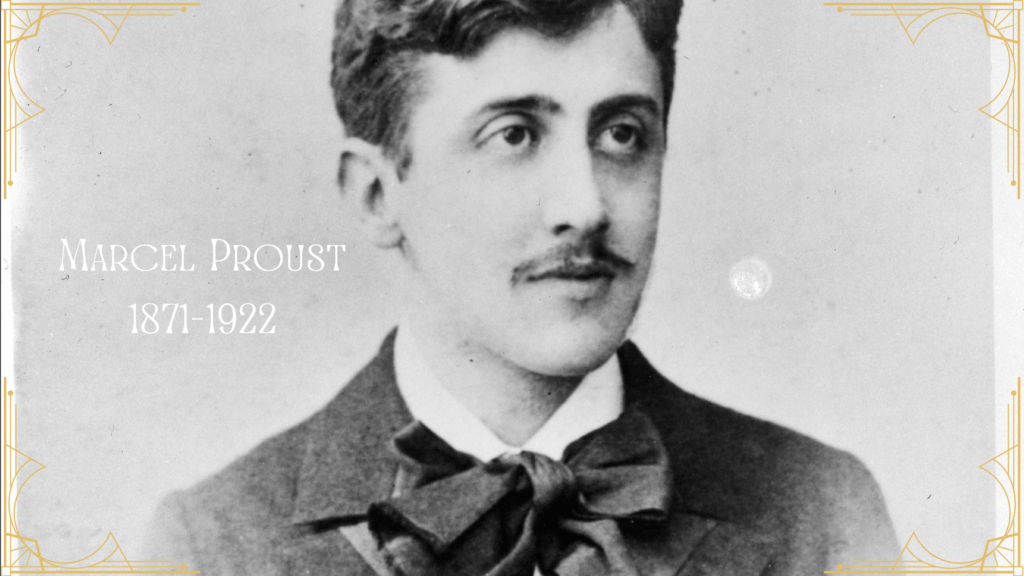

And it was on that late Saturday in November, in a building in Paris, at 44 rue Hamelin, in the 16th arrondissement, in a building that is now a hotel, between five and six o’clock in the evening, that Marcel Proust died. He was fifty-one years old. He had spent the last few months madly correcting and annotating his pages. He had managed to stretch his illness long enough to get to the end, long enough not to leave his work unfinished.

One hundred years later, the world celebrates him. Book upon book has come out, about him and his books; short films have been made and podcasts recorded; conferences have been convened and exhibitions staged. At the Père Lachaise cemetery, his grave is a slab of black granite; there is never a shortage of flowers. Because those who are passionate about Proust, his world, his novel, are often capable of infinite, adoring, affectionate devotion.

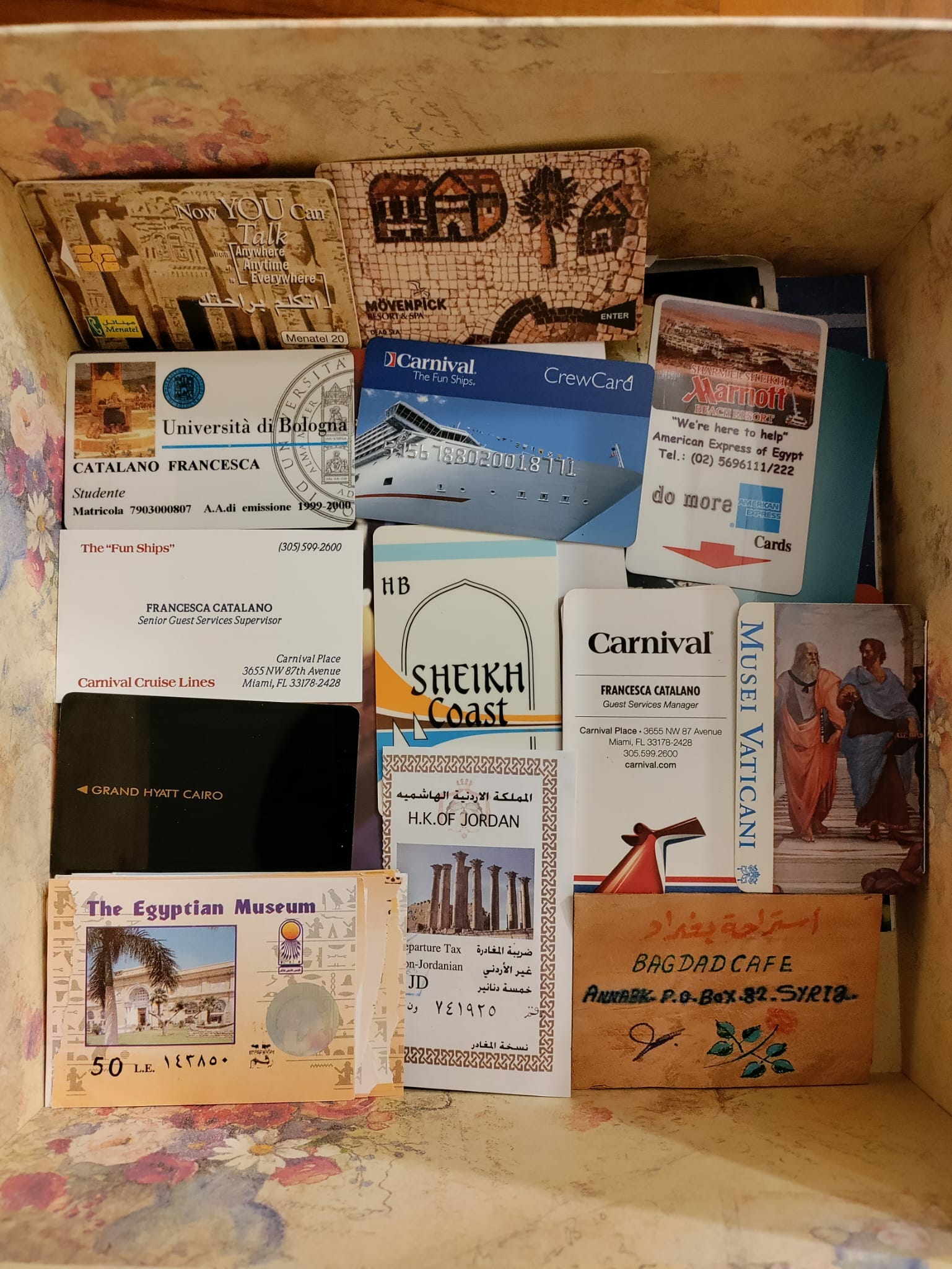

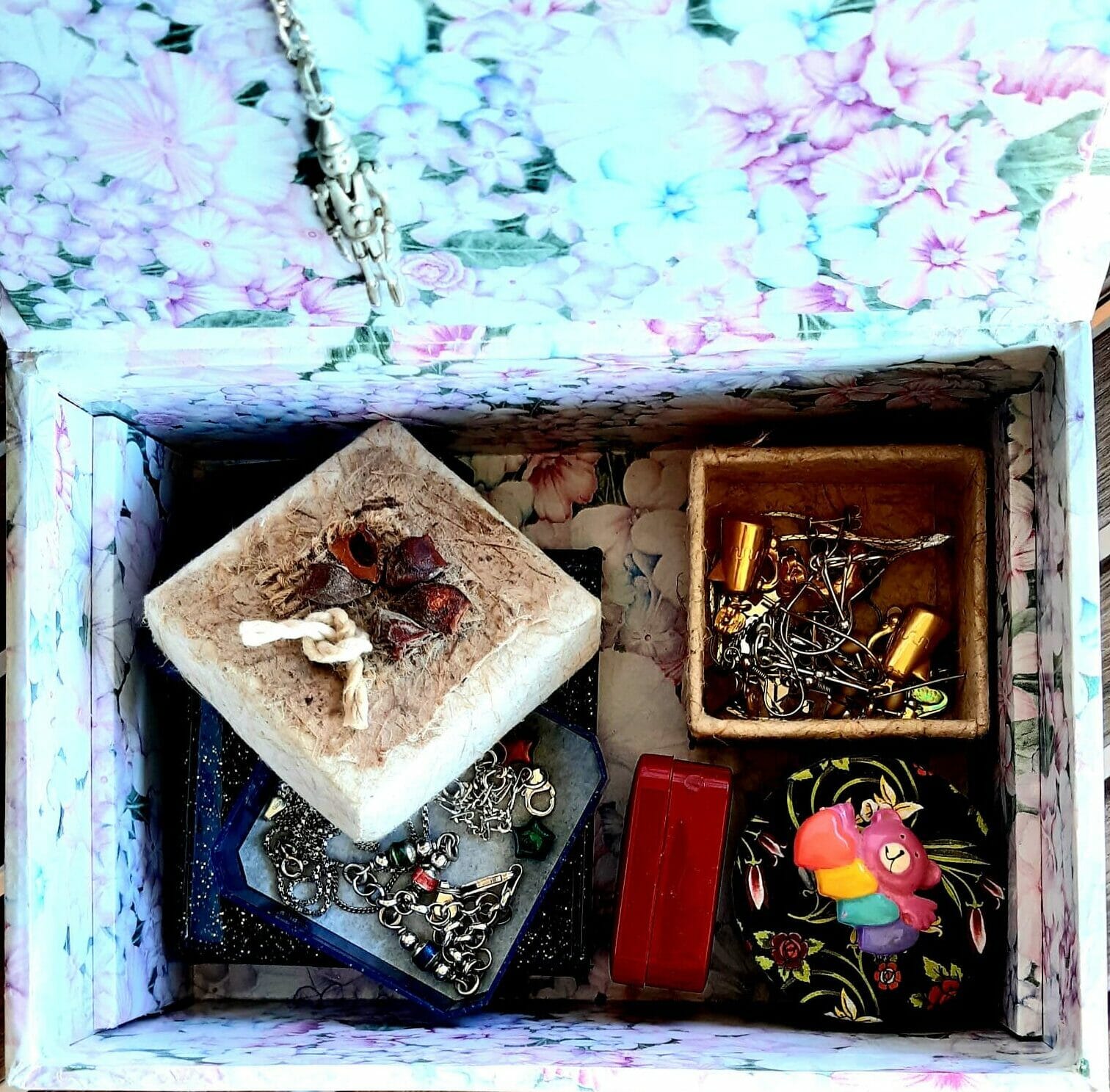

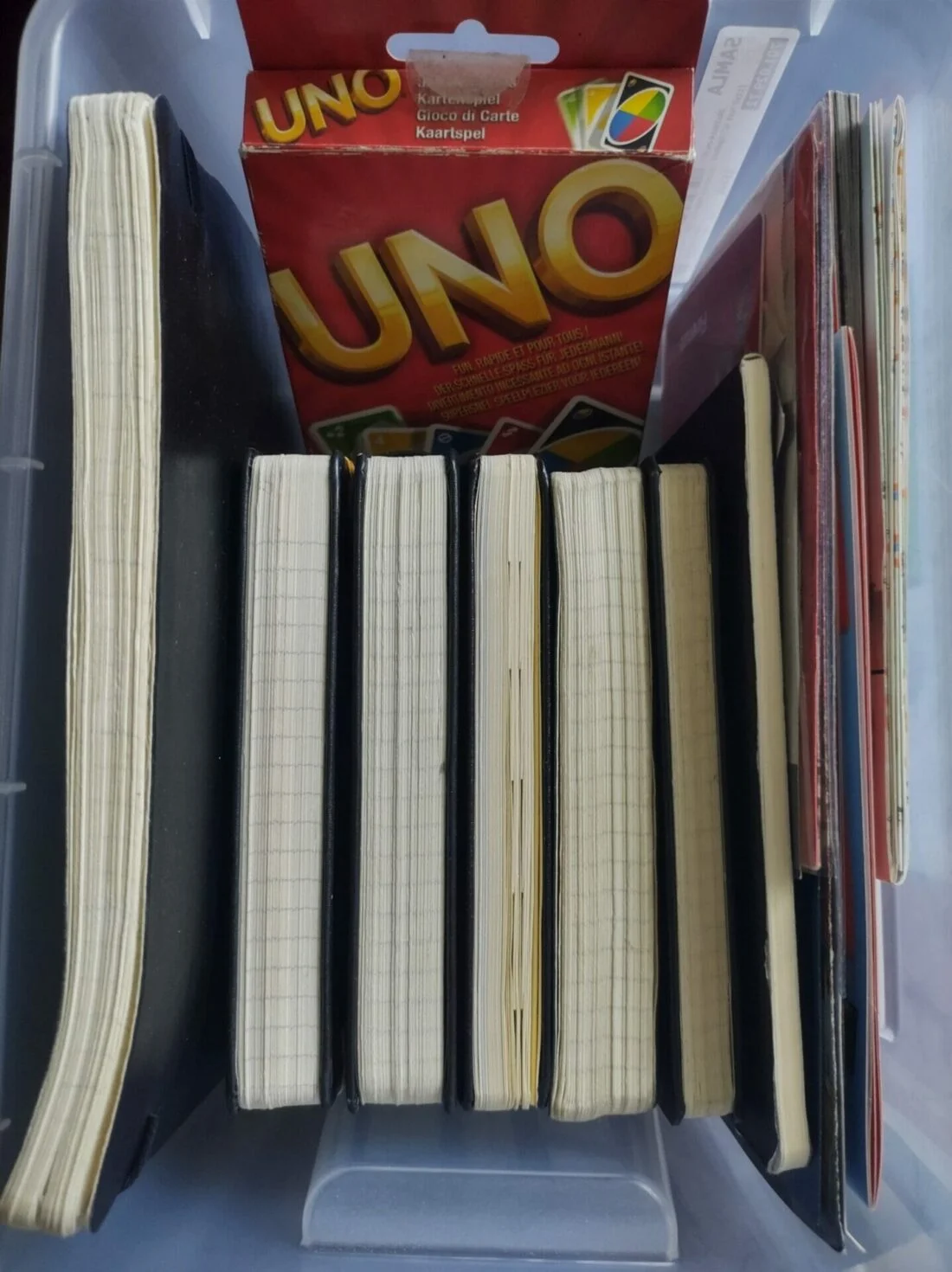

The memory of objects

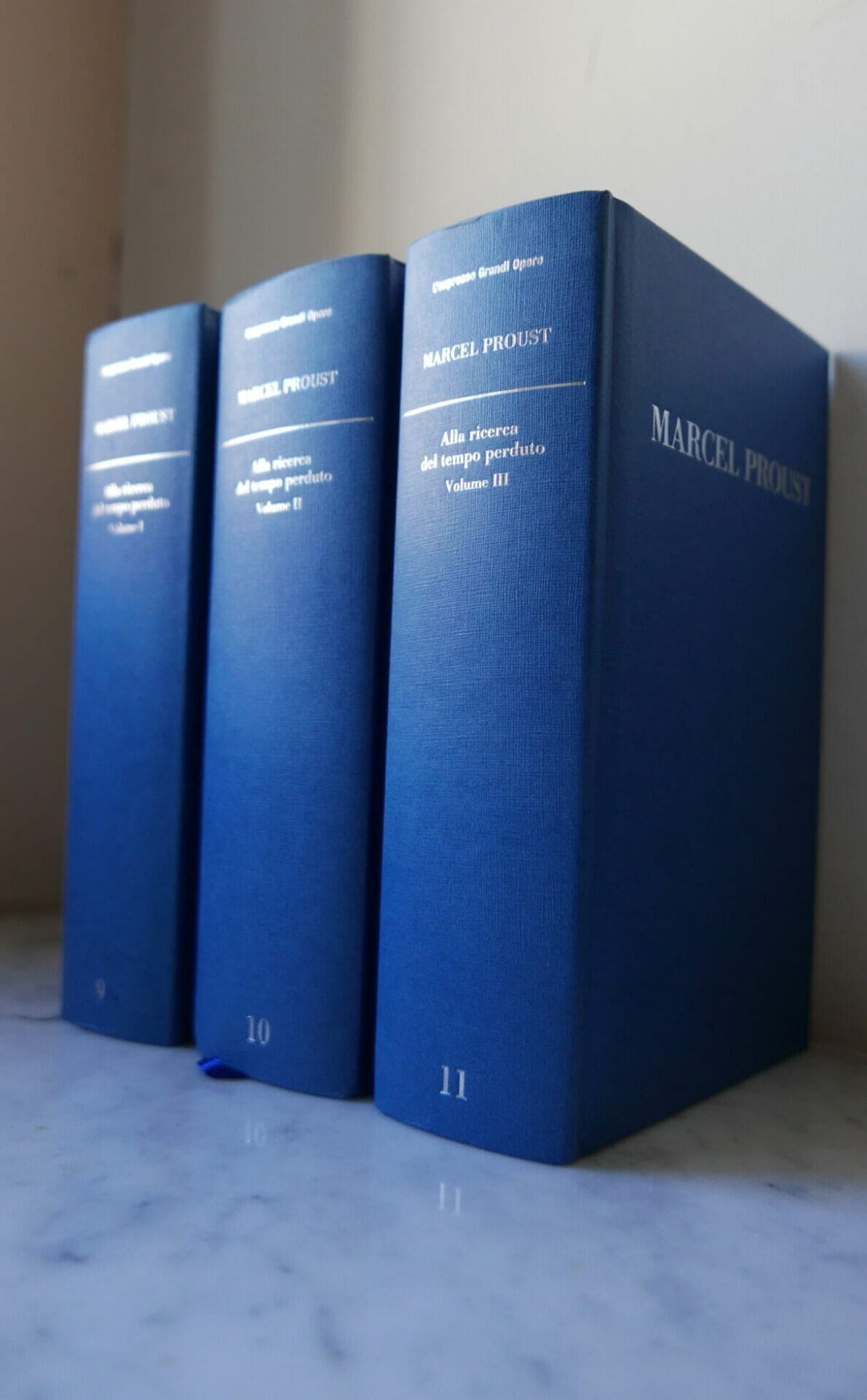

His novel, A La Receherche du Temps Perdu, or Remembrance of Things Past holds the record for the longest novel in the world. Perhaps – probably – for this very reason, many potential readers shy away from opening it, and thus they remain readers in possession of a form of power, while the seven volumes of the world’s longest novel gather dust atop some shelf, in an elegant slipcase edition.

Even those who, because of its overly imposing size or some other more or less valid reason, have not read Proust, are familiar with the mechanism of involuntary memory, which the mammoth novel only explores by telling of a world of childhood memories on which the doors of perception open wide, thanks to a madeleine, a small French cake dipped in a cup of lime tea – the taste of memory is revealed in the memory of objects.

Let’s try to let these objects speak, then, so that they can tell us something about Proust, about his work, about the way in which this mammoth novel is able to alter perception: of those who read it, of those who intend to read it, of those who do no more than just approach – even through others’ stories and accounts – the enigmatic moustachioed gentleman who was able to conduct a symphony of memory, letting the objects of everyday life play together.

The objects of the Recherche, piled up in magic boxes that play like music boxes, compose the melody of memory – perhaps it will sound like the little phrase by composer Vinteuil, the music evoked throughout the novel, the music that in a way is the soundtrack of this passionate search for lost time.

The room with cork walls

In Paris, in the heart of the Marais, in an old hôtel particulier that looks like a small castle, there is a museum that tells the whole story of the city. At the Musée Carnavalet you enter for free, and inside you discover a world. It is like opening a first magic box, which in turn contains many other smaller boxes.

At the Carnavalet, you will find medieval shop signs, but also the furniture from the Temple Prison, where Marie Antoinette was imprisoned during the Revolution, as well as little Louis, who never got to be king of France because France revolted against the monarchy when he was still a child, and condemned him to death.There is, too, Proust’s bedroom.

Nella camera di Proust

With its bed, desk, walking cane, screen, worn velvet liseuse armchair. And above all – the detail that perhaps makes the most impression – with the cork panels on the walls. The furniture and the cork panelling, to insulate against the noise of the street while the writing of the novel proceeded at a pace completely incompatible with that of the world outside, are those of the years spent in the Bd. Haussmann, following the death of his parents, before Proust’s move to rue Hamelin in October 1919: his last home, which was supposed to be a temporary accommodation, and was instead the definitive one.

There was no heating there, the flat was unfurnished; a few weeks after moving in, Proust learned that he had won the Goncourt Prize with In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower, the second volume of his mammoth novel.

La chambre de Marcel Proust présentée au musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris © Pierre Antoine / Paris Musées

It makes quite an impression, seeing that bed today – so small, so cramped. It does not look comfortable at all, and yet that is where the masterpiece novel was written. It also makes an impression to think that Proust’s coat is also kept at the Musée Carnavalet, the old frayed coat, with its fur collar, that appears in the photographs and descriptions of those who knew him, such as Cocteau.

It is a fascinating story of Proust’s coat and furniture, which were finally donated to the museum after various transitions. It is fascinating because it is the story of the devotion of the perfume industrialist Jacques Guérin, who spent much of his life ensuring that his heirs did not throw it all away, in an impulse of damnatio memoriae that was not unfamiliar to the shame of his brilliant relative’s sex life. Haussmann had given most of the family furniture to a brothel for homosexuals.

Lorenza Foschini reconstructs the story in her book Il cappotto di Proust (Mondadori), and reading it before wandering through the rooms of the Musée Carnavalet makes the experience of observing those sleeping objects, which lived their life as things in the service of such an unusual character, even more unforgettable.

Not only on the walls, some people keep corks for collectibles, or even as souvenirs of bottles uncorked in company or on special occasions.

The Magic Lantern and the kiss goodnight

In the life of an insomniac, nothing is as important as the nights. The first volume of the Recherche, is dedicated to childhood – the very first hunting ground of the time that our lives force us to lose, so that it may pass, so that life may be – offers an immense space to the theme of falling asleep. To the breath of the night, to the evening kiss of the child narrator’s mother – that evening caress that in our adult lives we miss in an unbelievable way, because when we grow up the moment of falling asleep loses the aspect of protection it had in childhood, when there was, in fact, someone to watch over our sleep, even if we never wanted to go to bed.

Mary Cassatt, Mother’s Goodnight Kiss, 1888. CC0 Public Domain Designation. Image courtesy of Art Institute Chicago.

The child narrator, however, having been sleepless since childhood, despite the oh-so-sweet prospect of his mother’s goodnight kiss, is terrified by the expanse of identical hours that lie before him every time adults send him off to sleep; and he invents a thousand ways to fool himself, to reassure himself in the face of that frightening desert. It is incredibly easy for anyone who has experienced even a single night of insomnia to identify with his torments.

Except that he, the Narrator, is destined to become one of the greatest writers in the history of the world, and so it is not surprising that his way of conquering his fear of the night is through stories. Stories projected on the walls of his room, during the summers he spends in the heart of France, in Combray – or rather in Illiers, where his aunt and uncle have a beautiful country house – by a magic lantern, with coloured glass that tells the medieval legends of the Merovingians: of the queens and kings of France whose descendants are precisely the narrator’s contemporary noblemen, whom he grows up wanting to know – and who disappoint him, because they are not made of reflections of light on painted glass, but are often stolid and flawed women and men.

Closed windows

Childhood is the time when the Narrator learns what love is, and he learns it, a bit like the rest of us, through an intermediary: before he experiences his first love experiences, he hears the story of falling in love, he observes its consequences before he even knows how much of a part they will play in his own life – if only because the girl who is born from this falling in love is destined to be his first love.

The love is that of Charles Swann for Odette de Crécy, and it is a love that is somewhat asymmetrical, and for that reason, tremendously tenacious, like all the somewhat mistaken loves – crooked, difficult, morbid and unhealthy – in Proust’s work.

Swann is a friend of the family; ironic and refined, a dandy of the highest order, so refined as to be simple-minded, as well as incapable of the slightest constraint, passionate about art, an amateur of the purest genius but too busy with lunches, parties and petty cultural ecstasies to succeed, alas, in transforming his talent into a lasting work, which would require a dedication and self-denial that he does not have, or perhaps, more appropriately, that he does not feel like discovering in himself.

Odette is a very young prostitute, although it is not appropriate to say it, and the reader is only allowed to guess at it, therefore, by fleeting allusions. Her mother initiated her into the trade when she was still in her teens; but she, Odette, has no intention of ending up like the Nanas or Ladies of the Camellias with which the novels of the second half of the 19th century in France abound; she does not even dream of allowing herself to be exploited and then spat on by the high society that despises her.

And she succeeds, in fact, in an extraordinary feat: not only does she seduce Swann, she makes him fall in love in the only moment when she is not posed to please him, but when she bends down and resembles for a single instant a girl painted by Botticelli in the Sistine Chapel – but that instant is enough.

Boldini's Portrait of Elizabeth Drexel Lehr | Swirls of escape

Then and there, she drives him insane with jealousy, leaving the shutters – jealousies – of her house closed, so that he doesn’t know what to read inside those shutters, and desires with shocking force to appropriate all her secrets, her time, her hidden hours.

Finally, the naively snobbish young Odette, who puts three English words in a sentence without really knowing what they mean, just to set a tone, who loves chinoiserie and oriental fashions, who fills her house with chrysanthemums and who serves tea, or rather tea, with cream so soft it looks like a cloud, turns out to have a great talent, a great eye for fashion. She dresses so well that her clothes make her look seductive, dazzling as if she were not dressed at all; she dominates mauve, she performs spells of seduction. And she climbs all the hierarchies of high society, which initially rejected her.

The Light of Normandy

In Odette’s past there is a painting, a portrait, in which she poses in the guise of an androgynous brat, with the name Miss Sacripant – Miss Bratty, Miss Braggart. It was painted by Elstir, the famous painter in the novel, the genius of colour who knows how to capture the light in his marinas, who has an extraordinary atelier in Balbec, Normandy and is a hybrid stand-in for the Impressionists who revolutionised painting as the 19th century drew to a close.

Normandy is the land that inspires him, and it is also the destination of the narrator’s holidays: it is there that he experiences the most shocking revelation of his life, the intermittence of the heart that understands what happens through involuntary impulses, through gaps, through failures. In Normandy, among the rooms of the Grand Hotel in the imaginary town of Balbec, largely based on Cabourg – a town of waves and covered cabins, of wooden promenades and clouds, of cathedrals and pastures, of oysters and casinos – the narrator discovers that death and desire, emptiness and fullness, really exist and concern him. And that the names of the countries crossed by train construct a geography of shocking truth.

A small strip of yellow wall

The whole of Recherche is a challenge to death, to death that does not only mean ending life, no longer being, but also, and perhaps above all: to stop remembering, to interrupt the flow of the involuntary energy that animates objects in telling us about things, stories, events, small or large incidents, stumbles and pains.

The last volumes, written as the author’s death was approaching, and he knew it, he felt it, are a game of catch-up with the approaching death, a heartbreaking game because it is free, unconscious, daring.

Thus, when Albertine, the adult love of the narrator’s life, the girl he discovered he longed for in Balbec and stopped longing for in Paris, when he had managed to establish her firmly – too firmly – in his life, dies, what happens is that shortly afterwards, in an almost soap-opera trick, Proust pops up a telegram that is supposed to rekindle hope that she is not really dead, that she is, in fact, alive.

This is not the case, and death thickens around it with even more insistence; yet, there is a halo of hope that ends up surrounding the death that in fits and starts in the final volumes, in the form, also, of the destruction of the First World War, that devastates the world known up until then, that stops time in a present of ruins, that gives the reader the impression that many more years have passed between the narrator’s youth and his maturity than have passed.

View this post on Instagram

The hope is not that death does not exist, of course; Proust knows very well that it does exist, he knows this also because he knows its counterpart, the frenzied and fierce desire that diametrically opposes it. But he also knows that there are cases in which death is not forever: this is the case with the death of artists, and in particular, the death of his writer friend Bergotte, modelled on the real-life character of Anatole France.

And, in turn, a stand-in for him; for Proust. Bergotte died in front of a painting by Vermeer, the View of Delft, lent by the Hague Museum for an exhibition of Dutch painting – an exhibition that was indeed held in Paris, and to which Proust himself wanted to go, although already ill, as Giovanni Macchia recounts in a beautiful essay, The Angel of the Night.

Johannes Vermeer, Veduta di Delft, c. 1660-1661.

Image courtesy of 'Mauritshuis, The Hague'

Up until his last moment of consciousness, Bergotte, who is very ill, who has eaten boiled potatoes and then at all costs wanted to go and see the painting, is obsessed by the perfection of one detail of the work: a small strip of yellow wall, of such beauty that it is worth his whole life – the life of an artist, dedicated entirely, to beauty. So much so that ‘the idea that Bergotte was not dead forever does not have the character of improbability’; and the same applies to Proust.

Above the rooftops of Paris, toward eternity

Fin

Ilaria Gaspari

Ilaria Gaspari collaborates with various journals and teaches writing. She studied philosophy at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, earning her doctorate at the University Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne with a thesis on passions in the seventeenth century. In 2015, her first novel, Aquarian Ethics, was published by Voland. In 2018, for Sonzogno, Reasons, and Feelings. Love Taken with Philosophy. For Einaudi, she published Lessons in Happiness. Philosophical Exercises for the Good Use of Life (2019) and Secret Life of Emotions (2021), both translated into several languages, and Cinderellas and Stepsisters. A Botany of Beauty (2022). For Perrone, a literary guidebook, In Berlin-with Ingeborg Bachmann in the Divided City, is out in 2022. In the summer of 2022, the Proustian year, Emons Record produced its podcast, Chez Proust.

Credits photo: Chiara Stampacchia

Translation by Christian Jennings, Hypercritic Senior Editor.

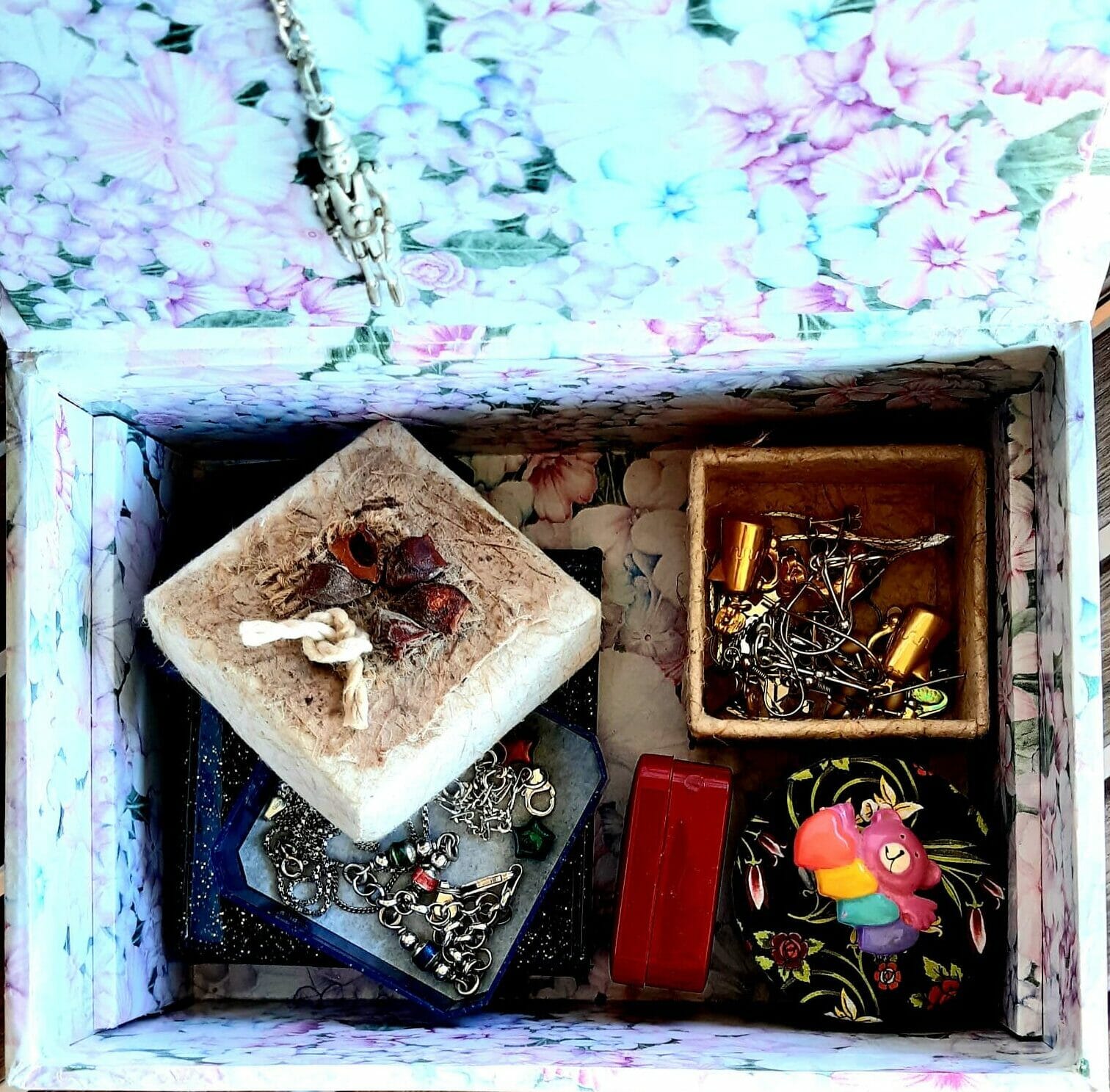

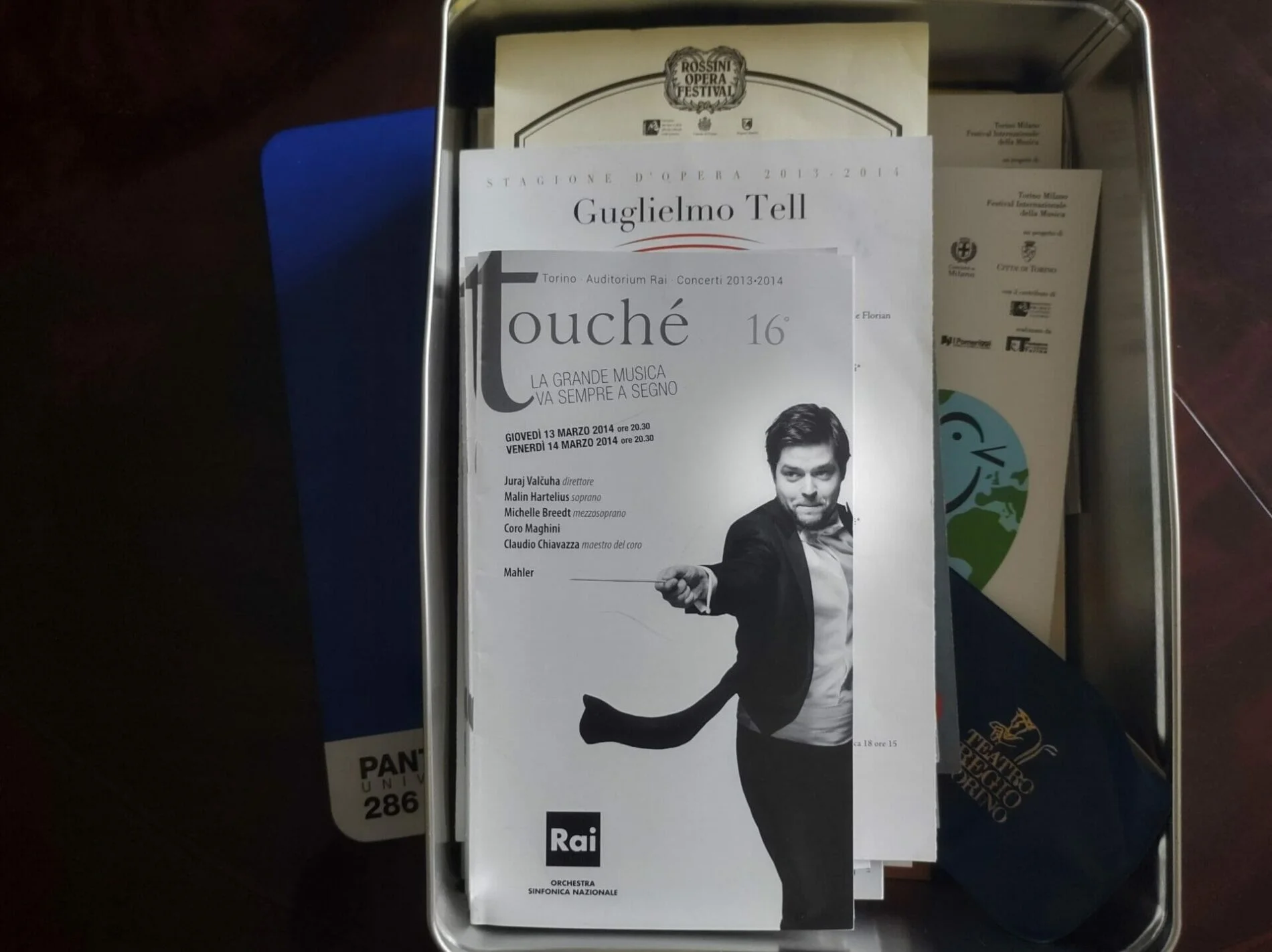

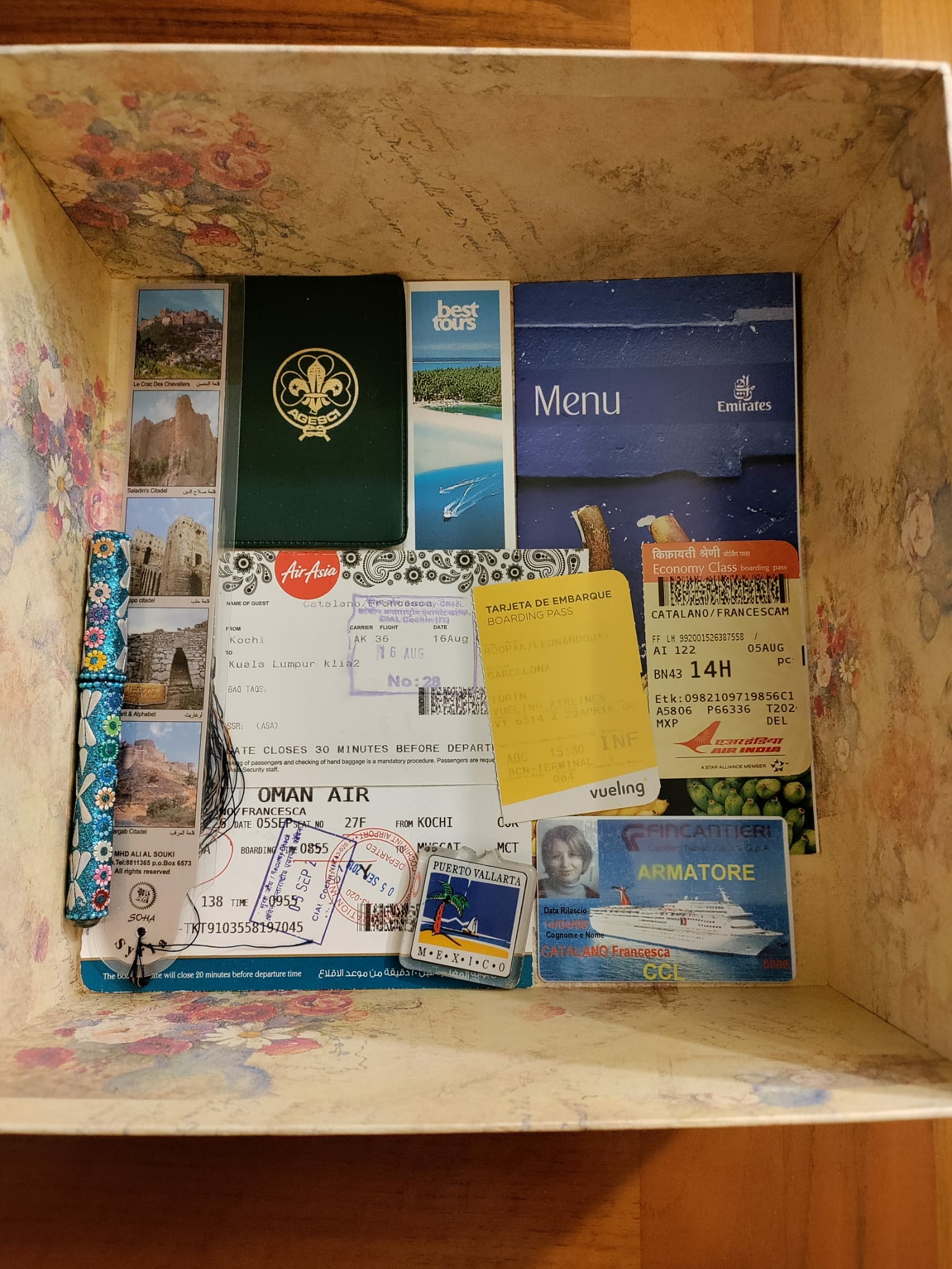

Some of your memory boxes

In the coming days, we will update the gallery with all the other photos.

Thanks to the people who participated by sending photos, sharing their memories with us and rediscovering a time gone by.