Severance TV Show | Identity without memory

Creator

Year

Country

Seasons

Runtime

Original language

Subgenre

Music by

“Who are you?” This seemingly straightforward question sums up the focal existential issue of this TV show. It’s there from from the get-go in Severance, Dan Erikson‘s acclaimed new offering, directed by Ben Stiller and Aoife McArdle, and which aired on Apple TV+ in 2022. The first season offered audiences one of the most compelling, well-constructed, and visually crafted shows in recent years.

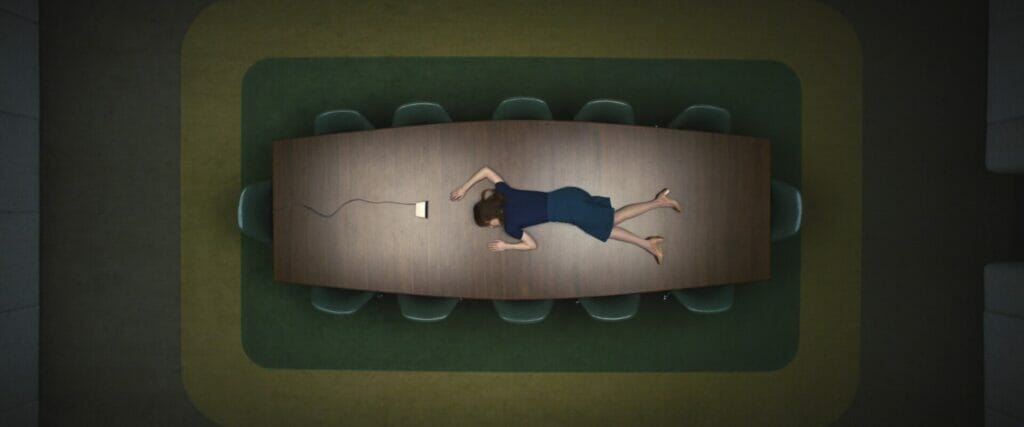

“Who are you?” is the question that Helly R, one of the four main characters, hears being asked as she wakes up on the table in a sterile, windowless meeting room. The voice that questions her comes from an intercom. The first, instinctive reaction is escape, but Helly discovers she is trapped without any memory of her past, not even her name. The starting assumption of Severance is something that anyone may have wished, feared, or imagined at least once in a lifetime: if it were possible to remove trauma, a memory that causes us pain, would our lives be easier?

- Severance’s starting point

- A captivating mix of genres

- An innate quest for freedom

- The power hidden in the details

- Bracing for the revolution

- When the realistic becomes unbelievable

Where to watch Severance

Severance‘s starting point

This theme, explored in films such as Michael Gondry‘s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), is taken to the extreme. We are in a parallel reality, in a dystopian past or present controlled by an industry, Lumon, that has managed to find a way to surgically separate the work and personal lives of its employees.

This is done through a procedure called “severance,” which employees voluntarily undergo. A chip implanted in the brain separates it into two watertight compartments: the work selves, the “innies,” start their life from scratch. While they retain the generic knowledge and skills learned from birth, these individuals have no memory of their experiences up to that point. On the other hand, “outies” know nothing about what goes on at work. Going up and down in the elevator to the severed floor of the company, the chip activates the innie or outie, which thus leads to two entirely separate lives, unaware of each other.

A captivating mix of genres

Severance is a realistically designed work of dystopian science fiction. Its dynamics and environments resemble an ordinary work environment, albeit with elements that generate a sense of estrangement. By the admission of co-director and co-executive producer Ben Stiller, the series draws these aspects from such sitcom staples as Greg Daniel‘s The Office (2005-2013).

The surface of the narrative maintains a light tone and the classic archetypes of office comedy. There is the gray, anonymous office worker who wants a quiet life and is fulfilled in his daily activities, Mark S. (Adam Scott), who replaces his mysteriously disappeared boss. Then we have the pandering, competitive, and greedy colleague, eager for production awards, Dylan (Zach Cherry). Dean Irving (John Turturro) is the senior colleague who knows the company’s principles, playbook, and history by heart and has an almost sacred respect for hierarchies. Finally, newcomer Helly (Britt Lower), struggles to adapt to her new surroundings. And she will be the fuse that detonates the tranquility of the office.

Beneath the surface of this monotonous routine lies a complexity skillfully constructed by the authors and brought masterfully to the screen by Jessica Lee Gagnè‘s cinematography, mixing science fiction and comedy with the register of thriller and Nordic noir.

An innate quest for freedom

The creators’ skill is to perfectly balance the questions and answers of the psychological thriller, creating a pressing equilibrium that generates involvement and never frustration. The more the viewer gets beneath the surface of this fictional universe, the deeper and more existential its questions become. This begins with the question of why some of the inhabitants of Kier, Lumon’s mysterious and icy city headquarters, decide to undergo the severance procedure. Then there are the workings of the procedure and its flaws, the implications this technology could have on humanity, even outside Kier, which is its incubator and laboratory.

Severance opens up a number of exciting ethical and philosophical questions. The first concerns identity itself: if people are deprived of their history and memory, what remains of their individuality? “Innies” are adults, in some cases even elderly, as with the characters played by John Turturro and Christopher Walken, yet their lives begin only when their “outie” decides to undergo the severance procedure. Their existence is fulfilled within the walls of Lumon and during office hours, they have to find an existential meaning in the small and childish rewards for achieving goals. Daily tasks seem meaningless: the MDR (Micro Data Refinement) department, led by Mark, spends the day cataloging random numbers based on the emotional response they elicit.

The four protagonists might well consider themselves slaves, on a par with the automatons of Westworld, or the replicants of Blade Runner. Except for all we know, they are flesh-and-blood people and spontaneously decide to undergo the severance procedure. In addition to an external conflict, with the organization that controls them, they experience an internal conflict for enslaving themselves of their own accord.

The power hidden in the details

Severance’s eerie effect stems as much from its themes as from its refined visual language. Every shot and every detail of the scene is carefully crafted to generate a specific reaction in the viewer. Lumon’s spaces (but also those of the city, Kier), are huge but empty, aseptic, and geometric. Overhead shots, characters placed in windows or bounded spaces, and faces ending on one side of the screen give the impression of a constantly controlled environment.

It is the principle of the Argo Panoptes of Greek mythology, or of the Panopticon, applied to prison institutions by the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham: the idea of a system that makes anyone controllable at all times, to the point of creating the impression of an invisible power that makes control itself unnecessary because it is introjected by those subjected to it. This is the same theme explored in George Orwell‘s literature.

Lumon, too, is based on an invisible power, passed down for generations by the Egan family, which has turned its history into a kind of religion. In this aspect, Severance offers a subtle and ironic critique of the cult of capitalism, which becomes even more relevant in the aftermath of the pandemic and the “great resignations“.

Bracing for the revolution

Another key feature is the choice of colors: green and blue, Lumon’s colors, dominate the “innies” world. Red is always a disruptive element, generally referring to the world outside: Helly R. has red hair and wears warmer colors as she infects her colleagues with her quest for freedom. It is a kind of transposition of the choice between red or blue pill presented to Neo in The Matrix. Cold colors dominate Mark’s house, except for a goldfish. Red is also the envelope of the note that his former boss Petey delivers to him in the outside world, warning him about the truths hidden by Lumon. As pointed out in Hypercritic’s Red Exhibition, this primary color can be a symbol of revolution.

Another leitmotif is food, as illustrated in the video essay by the Nautilus Files YouTube channel, full of analysis and theories about this TV show.

When the realistic becomes unbelievable

Severance is a believable tale because it is realistic, compelling, easy to identify with the four protagonists, and because heroes and enemies are always more complex than they seem. The show achieves this through an ambitious vision, a refined but accessible visual language, and never-predictable writing. But a key role is played by performances. Starting with Adam Scott, co-producer of the series, who until now had been seen mostly in comedies. Alongside the already mentioned actors star two outstanding antagonists: the mysterious Harmony Cobel, played by Patricia Arquette (co-producer of the show), and the indecipherable Milchick, by Tramell Tillman.

The cast’s skill is knowing how to work on nuance, starting with tiny changes in facial expression when they switch from “innie” to “outie”. Scott explains it well: “The important thing was to get across the idea that, innie or outie, it was still the same person. And so we worked by addition or subtraction, depending on Mark’s two halves’ circumstances. Because even if they are not aware of each other, feelings and sensations pass from one to the other.”

The whole point of Severance is just that: an exploration of the complexity of the individual in all its nuances. Of how one must come to terms with suffering and hardship. But it is also an enjoyable show, a witty satire on capitalism and the place that work has and should have in shaping individual identity.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic