Fear & Hunger | The RPG Video Game That Turns Suffering Into Art

By

There are video games that scare you. And then there’s Fear & Hunger, which takes suffering on a whole other level.

Published in 2018 by Happy Paintings and developed solo by Finnish developer Miro Haverinen with RPG Maker, in just a few years, the video game has become the title everyone knows about but almost no one actually dares to play. Described by many as “the cruelest game ever made”, it has earned a controversial reputation that has transformed it into an online survival-horror cult, fueled by streamers, YouTubers, and forums that recount its atrocities as if they were a cursed movie found on VHS.

Like Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Fear & Hunger owes much of its fame to its online virality and its ability to traumatize players more than simply entertain them. And, like Lobotomy Corporation, it shares that dimension of a dark and indecipherable object, difficult to explain to those who haven’t experienced it firsthand, yet impossible to ignore once encountered.

There is no heroic path: you die, you lose, you start again. And it’s precisely in hopeless repetition that the narrative is constructed, with more emphasis on failures than successes. But what seems like pure cruelty and despair hides a work capable of redefining what a horror video game can be.

It’s a title that doesn’t entertain: it challenges the player. It doesn’t reassure: it devastates them. And that’s precisely what made it a cult classic, loved and hated with equal intensity.

Between Fear and Faith: Entering the Dungeon of Rondon

In the corrupt kingdom of Rondon, a man named Le’Garde – a revolutionary, perhaps a heretic – is imprisoned in the dungeons known as the Dungeon of Fear & Hunger. This is the starting point of the game.

Beyond its cruelty, Fear & Hunger conceals a complex narrative structure. The seemingly simple mission – finding Le’Garde – soon reveals itself to be a pretext for descending into the corrupted lore of the game.

The player chooses one of four protagonists, each driven by different motivations. Cahara, the mercenary, seeks redemption from his past sins. D’arce, Le’Garde’s knight, attempts to save him out of loyalty and love. Enki, the dark priest, sees an opportunity to ascend to a higher power. Finally, Ragnvaldr, the outlander, seeks only vengeance for the war crimes suffered by his people. All four represent different perspectives on the same destiny: to challenge the cosmic order of the world.

A Pantheon of Cruel Gods and Corrupted Faith

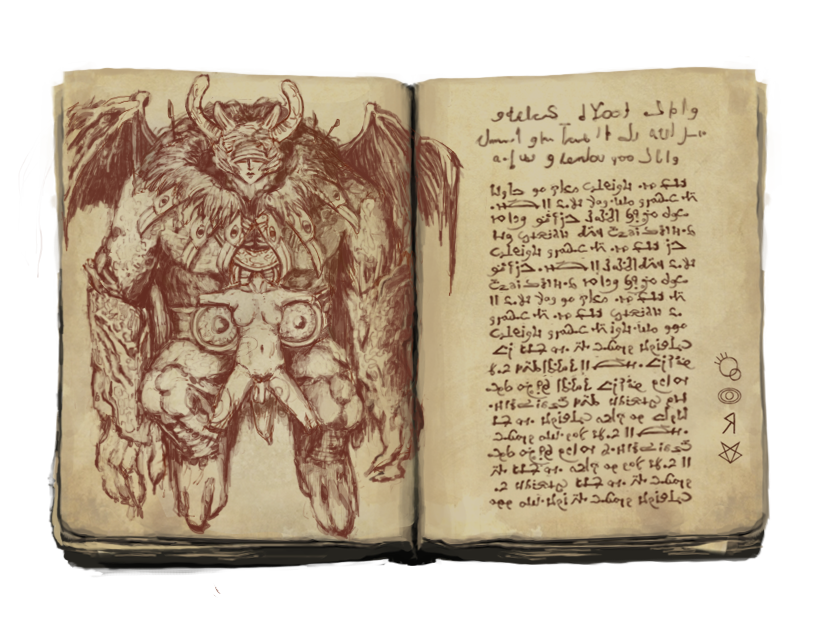

The Fear & Hunger universe is dominated by a pantheon divided into three categories: the Old Gods, primordial forces that embody instincts and cycles; the New Gods, ancient humans who became divinities through ascension, and the Ascended Gods, intermediate beings born from the contact between mortal and divine. Among these, a few stand out. There is Sylvian, goddess of creation and desire, whose love manifests itself in acts of flesh marriages. Gro-goroth, god of destruction, demands blood sacrifices in exchange for power. Alll-mer is a former mortal who achieved divinity by promising redemption, but only through the dissolution of the individual.

These gods, however, offer no salvation. Their blessings corrupt, their cults degenerate, and spiritual ascension often coincides with the loss of humanity. It’s a vision of the divine that harks back to both Berserk and Lovecraft.

The actual narrative, as in the best dark fantasy, lies in fragments: books, relics, and conversations with the few survivors of the madness. It’s a story the player must piece together on their own, deciphering superstitions, cults, and myths reminiscent of the cryptic structure of Dark Souls and the theological horror of Bloodborne.

Pain as a Rule: How the Game Redefines Difficulty

As the player ventures into the dungeon, a labyrinth unfolds. Every corridor is a threat, every encounter a potential doom. The enemies are deformed jailers, aberrations, men reduced to beasts. Facing them is always a risky choice, and often escaping is the only strategy: Fear & Hunger quickly teaches that survival isn’t about fighting, but knowing when to give up.

The combat system is turn-based. You can target specific limbs to weaken your opponent, but the same logic also applies in reverse: losing a leg or an arm can permanently compromise your ability to react. And post-battle healing isn’t always available.

Resource management is equally cruel: hunger, sanity, and physical integrity deteriorate rapidly, and food and medicine are extremely scarce. Even saving is subject to chance: often, sleeping in a bed allows you to save the game only if you succeed on a coin roll. Miro Haverinen designed everything to make any progress precarious.

While most RPGs reward growth, Fear & Hunger turns that logic on its head. There are no experience points: knowledge is the only form of advancement. The player learns by dying, remembering traps, paths, and strategies, even if their in-game character is unaware of them. It’s almost a roguelike structure, where every failure becomes part of the process.

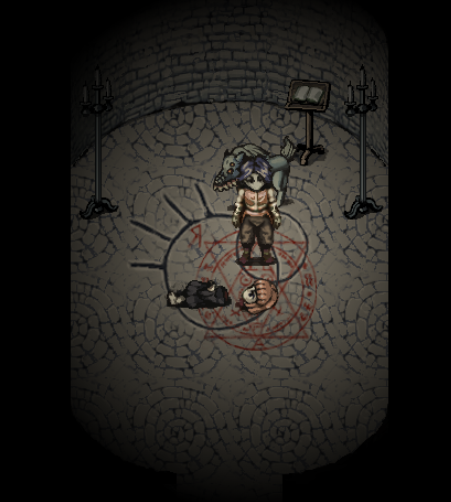

The only way to strengthen yourself is through the Hexen system, which allows you to use soul stones collected from enemies to learn skills.

Violence, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Horror

In Fear & Hunger, each enemy represents a distinct manifestation of the pain and corruption that dominate the world. Their intentionally disturbing designs oscillate between the grotesque and the sacred, blending religious, sexual, and anatomical symbols until humans, monsters, and gods become indistinguishable.

Violence is tangible; it leaves permanent scars. Every fight can result in mutilations, infections, fractures, or mental trauma that irreparably compromise the character’s survival. A severed arm prevents the player from wielding weapons, a lost leg slows movement, and madness obliterates lucidity. Pain thus becomes an integral part of the gameplay system —a resource the player must manage, much like food or light.

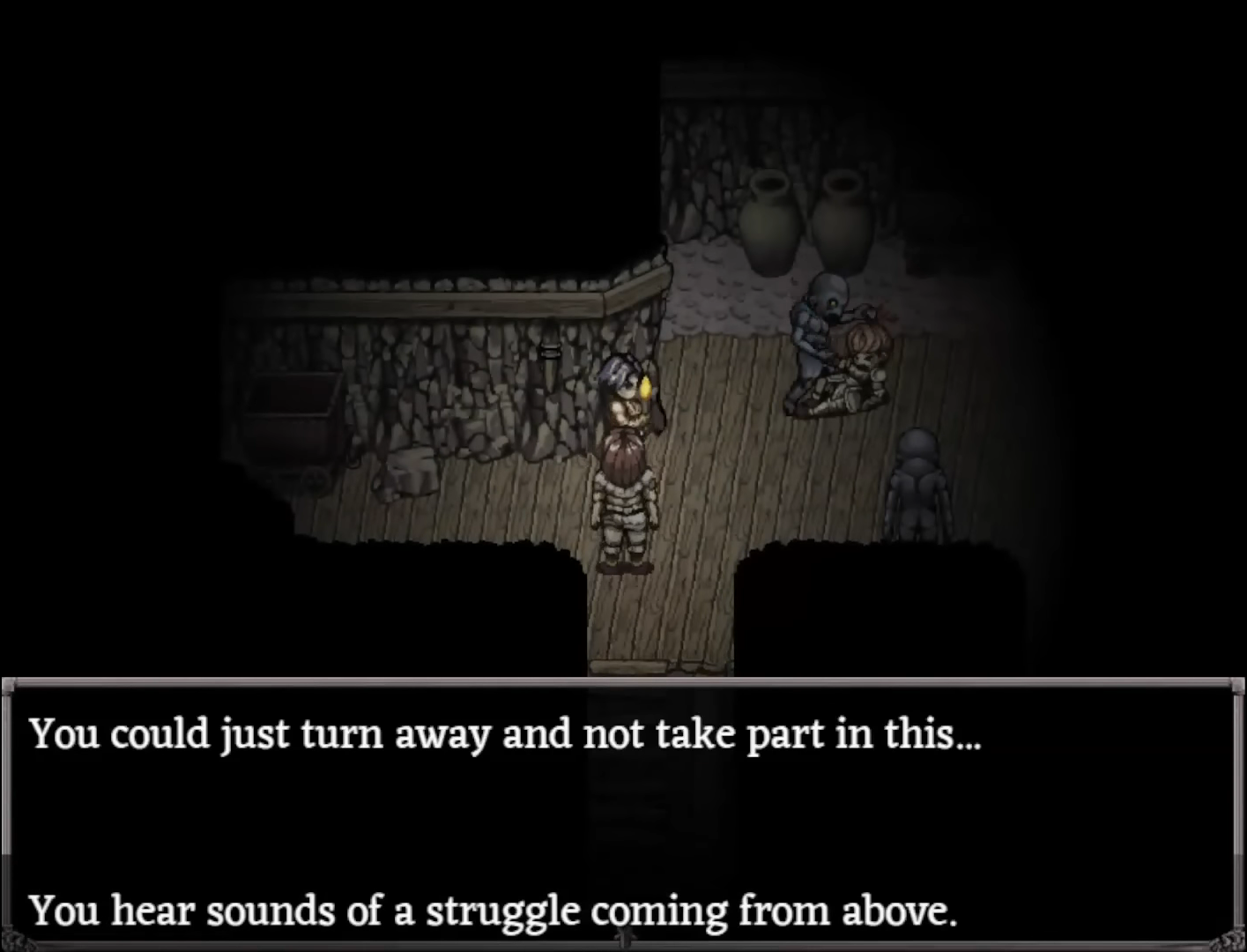

A central, often misunderstood, aspect concerns sexual violence. Fear & Hunger depicts it explicitly, brutally, and disgustingly, but never as an instrument of player power. It is always endured, never inflicted, and serves to underscore the theme of total vulnerability. Miro Haverinen has clarified that he doesn’t consider it a playful act, but a condemnation: a manifestation of the world’s brutality, not a means of entertainment. Precisely for this reason, it is perpetrated only by enemies. It’s a choice that makes the experience even more disturbing, but also consistent with its ethos.

The resulting sense of oppression is profound and constant. It’s a type of horror reminiscent of the existential suffering found in Silent Hill 2, while the graphic cruelty and uncensored depiction of pain recall certain movies such as Martyrs or Salò. Fear & Hunger doesn’t ask the player to overcome fear, but to stay, even when everything invites them to run away.

From Fear & Hunger to Termina: The Evolution of the Cult

Released in 2022, Fear & Hunger 2: Termina moves to the town of Prehevil, a 1940s war-torn village. Here, a group of sixteen characters face the cursed Festival of Termina, a cycle of destruction punctuated by the appearance of a yellow moon.

Gameplay-wise, Termina retains the brutality of its predecessor but delivers it more narratively and dynamically. Cyclical time influences events and interactions: there are three days, and the progression of events (or even just which character to recruit to your party) depends on when the player decides to do what.

Here too, death is inevitable and part of the learning process, but the broader structure allows for different approaches and greater attention to the individual protagonists’ stories.

One of the most significant aspects of Termina is the expansion of its lore. The mythology of the first game opens up to new deities, such as Vinushka, god of nature and biological corruption; or Rher, the lunar trickster who orchestrates the Festival; or the Sulfur God, an entity linked to the consciousness of Alll-mer. This multiplication of the pantheon makes it clear that the universe conceived by Haverinen is constantly evolving.

Thematically, Termina abandons the religious fanaticism of the first game to focus on alienation and trauma. War, memory, and madness replace sin and punishment. Prehevil is a microcosm of modern anguish, a city where horror no longer descends from the gods, but from the human mind. An anguish reminiscent of the decadence of Pathologic.

The underlying question, however, remains the same: how much pain can a human being endure before recognizing himself in the monster that devours him?

Remaining in the Abyss: Haverinen’s Vision and Legacy

Seven years after the first Fear & Hunger, Miro Haverinen continues to expand his universe with the same single-minded dedication with which he created it. Following the success of Termina, the Finnish developer has confirmed new free updates, designed to broaden the narrative and deepen the characters’ stories.

At the same time, he is working on a new project set in the same universe, perhaps a prequel or a side chapter.

I have a couple of more fleshed out ideas, but it’s too early to tell if either of them become anything more. When F&H1 was close to being done, I thought of a thematic throughline for a trilogy of games. So I have a pretty good idea what F&H3 would be about even if there is a lot of freedom in the surface story to set it in different places in the timeline. […] The other is a more conservative idea that’s closer to the established formula, while the other one is a wild card. I’d probably prefer to stir things up because I fear if things settle down to a more clear formula, any deviation from that in the future would be more difficult. I do have some ideas for potential spin-offs too, so who knows, I might make something completely different than what’s on my mind currently.

Miro Haverinen in an interview with DarkRPG

In a gaming landscape where horror tends toward spectacularity, Fear & Hunger remains an anomaly. The project keeps growing without losing coherence. Its secret lies in offering no escape, only immersion. To survive one more day, even when all seems lost.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic