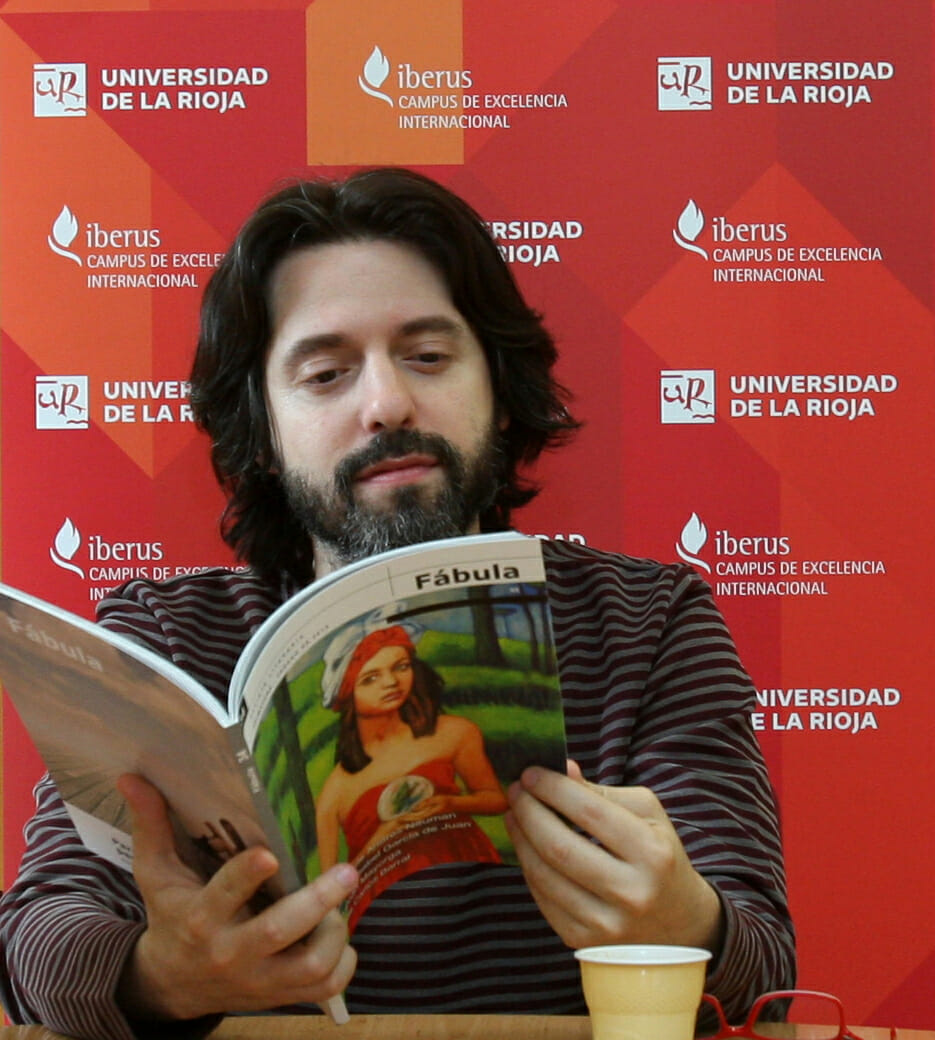

Listening to Spanish-Argentinian writer Andrés Neuman speaking at the Turin International Book Fair, on May 21, was exactly like reading one of his books. From the first bunch of words, you knew by instinct it would be good. In a conversation with Italian journalist and writer Gaia Manzini, the 45-year-old author discussed his 2003 novel Una Vez Argentina (Anagrama, Barcelona), a chronicle of his family’s history since his great grandfather’s migration to Argentina.

That an author may come to a book fair to present a 20-year-old novel might sound strange. But when it comes to Una Vez Argentina, it makes sense. Not only because the book was rewritten several times in the 20 years after its first publication, and it has recently been published in its third edition. But because this process tells a lot about the nature of the novel. After all, all family anecdotes have something in common: they are repeated over and over again.

Where memory begins

“There is no text more reread and more difficult to write than our childhood”, Neuman said about the rewritings. But what makes it even harder to put the story of a life in words — especially one’s own — is that childhood isn’t even where it really begins. “There is a convention that memory begins with our own recollections. This is a mistake,” Neuman explained. According to the author, the stories we’ve been told about ourselves, our parents, and our ancestors are crucial to the way we project ourselves into the past. They are a fundamental part of who we are.

For convincing it might be, this approach to memory evidently raises some head-scratching for a writer. One could easily imagine the twenty-something Neuman wondering: where does this story really begin? Am I digging too far in the past? Or is this not enough? In part, the answer to this question is rooted in contingency. If there’s someone to tell the story, then it’s memory. If there isn’t, then it’s history. Yet, choosing where a story begins is constitutively an authorial choice. In this case, it begins with an escape to Argentina. And the borders of memory interestingly end up coinciding with national borders.

The provisional motherland

Speaking about his native country, Neuman described Argentina as “a provisional motherland”. A place where all grandparents are immigrants and all grandchildren are emigrants. This condition of provisionality is the core of the experience of migration. Even when you know you’re gone forever, you keep on wondering if you’ll ever be back. Just as Neuman’s French great-grandmother Louise Blanche, who never stopped missing her country even if she spent half her life in Argentina.

When asked about his relationship with his adoptive country, Spain, Neuman described a sweet limbo. As long as he was within his house walls, he was still in Argentina. But as soon as he crossed the door, he found Spain outside. And eventually, he understood his place in the world was the doorjamb. His life is not across a certain border but on the border itself. Possibly, this is the only place a writer can be. And for certain, the only one Neuman could write this specific story from.

To find an ending

When he first began to write Una Vez Argentina, Neuman was often told he was probably too young to be working on a memoir. An objection which he proudly rejected, he explained. He did it rightfully: one is never too young to write their own story. But it could be observed that in the case of a family story things are a bit more complicated. Writing the story of your family doesn’t only mean you should choose a beginning. It also entails you should give it an end. That is to say, the author must at least fictionally presume that the story ends with them. And with them at the moment they’re writing it. The second border of his memory is Neuman himself.

That the author has rewritten his novel three times is the utmost demonstration of this complexity. The reader might wonder: will he do it again? Memory is constantly changing, often outside our control. We acquire new information, we change our point of view. In the words of Neuman, there is no text more reread. And yet, it seems like the author has found an answer — one which sounds rather convincing. “Our childhood ends when we change our questions. When we ask our mothers and fathers other questions.” And knowing he has new questions in mind, we can only be waiting for Neuman’s next work.