Juror #2 (2024) by Clint Eastwood Review | If Morality Clashes Cruelly With Life

Runtime

It was a dark and stormy night when Justin Kemp (Nicholas Hoult), not yet juror #2, hit a deer on his way home. He couldn’t find the animal, so he continued, thinking he hadn’t severely hurt it. It was a tough night. He couldn’t imagine how much more challenging it could have been if he had just looked better.

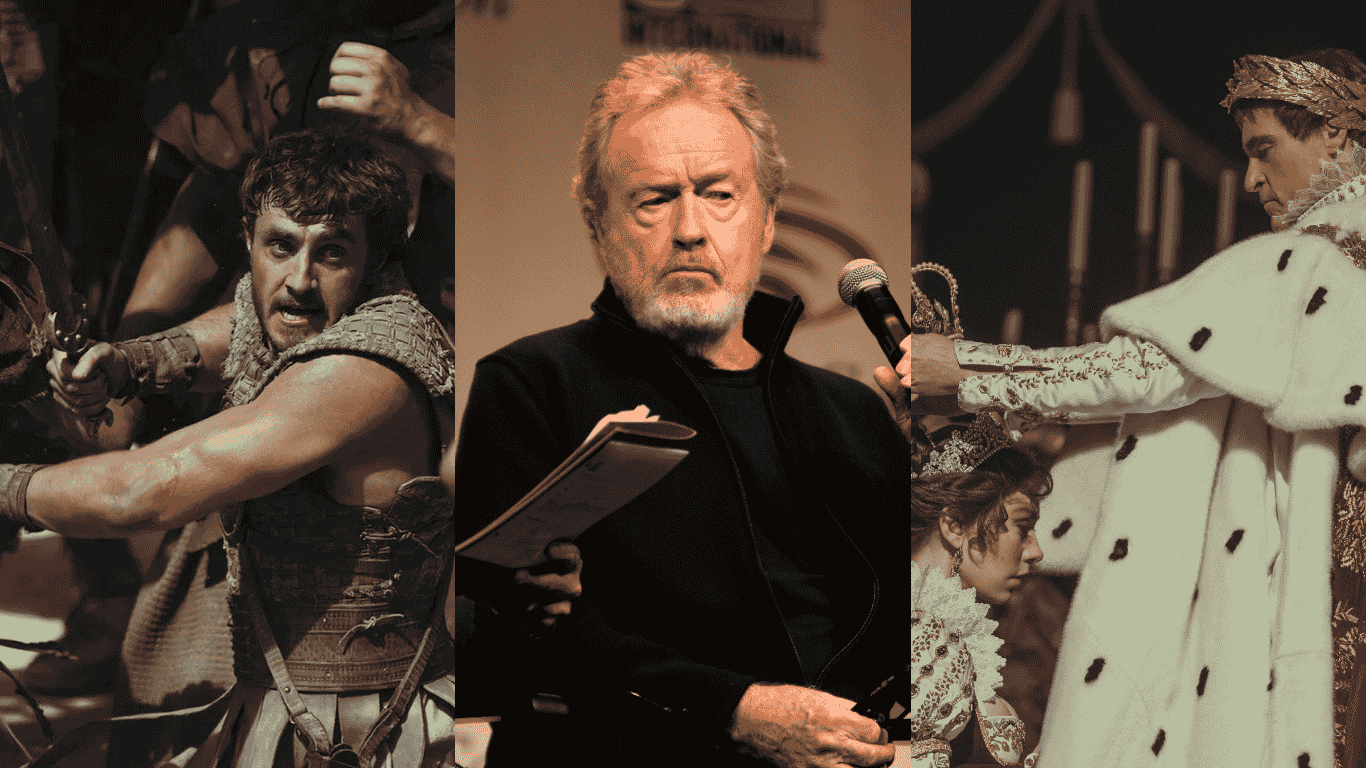

Directed and co-produced by Clint Eastwood, Juror #2 is the director’s 40th and last film. An elegant veneer of legal drama hides a narrative that is also a thriller, with a hint of Western that recalls the artist’s origins. However, the director uses this work to reflect on the shortcomings of public institutions and politics and to make a profound socio-political critique. Moreover, the plot underlines the weight and difficulty of ethical choices when justice collides with truth and salvation.

Juror #2 premiered on October 2024 at the AFI FEST, and Warner Bros. initially conceived it as a direct-to-streaming release. However, it eventually opted for a limited release, and the film played in fewer than fifty domestic cinemas in the US. In contrast, it received wide distribution in the United Kingdom and throughout Europe. Critics generally expressed positive opinions, particularly regarding Eastwood’s ability to convey political ideas and demonstrate great self-reflection.

- The Hard Way to Redemption

- When No One Is Wrong, There Lies the Real Tragedy…

- Like a Western, but in the Courthouse

- The Age of Denunciation and Lack of Answers

The Hard Way to Redemption

Justin (Hoult) is a young journalist about to become a father for the first time. He’s married to Ally (Zoey Deutch), who is very worried about this pregnancy after losing her first child. Justin is a recovering alcoholic trying his best, still grateful to her for giving him a second chance. When the state of Georgia summons him for jury duty, he also asks for an excuse to be with his wife. The judge denies his request, however, and he becomes Juror #2 in the trial of James Sythe (Gabriel Basso), accused of murdering his girlfriend Kendall Carter (Francesca Eastwood).

Faith Killebrew (Toni Colette) sees the Carter case as easy and accepts it because it could help her run for district attorney. However, as soon as the trial begins, Justin realizes the suspect is innocent. Another juror (and former detective), Harold (J.K. Simmons), believes Sythe is a victim of prejudice, too, but Justin doesn’t just have a highly developed sixth sense. The man didn’t kill his girlfriend. And it wasn’t a deer Justin hit that night. He’s Kendall’s murderer.

When No One Is Wrong, There Lies the Real Tragedy…

Eastwood believes in second chances and the possibility of overcoming one’s mistakes. It’s a spirit that links his work to other cult films such as Frank Darabont‘s The Shawshank Redemption (1994) or Ken Loach‘s The Angels’ Share (2012). Juror #2 has a reincarnated hero as its protagonist. Justin has had some trouble with the law and is still battling his demons, but he represents a possible redemption. He aims to change and start a life with a woman who believes in him. Since Sythe has a history with a criminal gang, Justin wants him to have the same opportunity. Still, he’s willing to do anything to preserve the happy ending he sees in front of him. Even sacrificing his ethics.

According to ancient Greeks, the real tragedy doesn’t arise when evil fights good, but rather when two just fronts clash. When Antigone confronts her uncle about burying her brother, he represents the law, while she represents mercy. They’re both right, and it’s hard not to understand Creon‘s reasons for sentencing a girl to death. Even though Justin is guilty of the murder, he’s completely unaware of what he’s done. That is, until the moment the murder is reconstructed. He didn’t kill the girl in cold blood or rage; it was an accident.

While investigating a crime, Juror #2 scrutinizes morality and the weight of personal choices. Can a single unintentional mistake result in a life sentence? Is justice more important than self-preservation, even if a fair verdict destroys more than one life?

Like a Western, but in the Courthouse

The film features several flashbacks, each with distinct styles and purposes. If the first is rapid flashes on a confused night, mirroring Justin’s vague memories, they become longer and more detailed as the trial progresses, underlining new aspects. The flashbacks initially act as a neutral narrator, piecing together the events of that night. After Justin accepts the reality, when it’s clear he hit the girl, their roles change, though: the scene pops up in his mind insistently as a cruel spotlight on his faults. Flashbacks evoke remorse and guilt, relentlessly forcing him to question whether confessing is the right thing to do. Until the end, they serve as a powerful counter-melody to the protagonist’s firm position, underscoring his inner struggle.

After some minor roles, Eastwood began his successful career as an actor in Western films. In Juror #2, he pays homage to his background through cinematography, storytelling, and sound design details. The retired detective Harold has a witty mind, a sense of private justice, and manners slightly reminiscent of an Old West sheriff. Sitting before a glass of whiskey, Justin looks like a lonely cowboy fighting his old ghosts. The soundtrack is never intrusive; it remains in the background, commenting on the events. On the contrary, rumors and natural noises create vivid results. They emphasize conflicting feelings and confusion, focusing on the most minor details, such as the click of a trigger or the sound of a step on a dry branch.

The intimate cinematography follows the point of view of different characters, and the camera becomes a detective of their inner turmoil. As in Westerns, the camera frames the characters from a very close distance. It focuses on their postures and facial expressions, underscoring the conflicts within themselves and their souls. There’s also a massive use of shot/reverse shot framing that fits perfectly with the trial clash but is also reminiscent of Mexican standoffs. It’s a choice that comes to fruition in the final confrontation between Justin and the persecutor, Killebrew, when it’s enhanced by the sound of a rattlesnake that transports the audience into the Old West. Yet classic Westerns revolve around two clear fronts: good versus evil, God’s land versus the wild desert. Justin’s alternatives do not clearly distinguish right from wrong. There’s only the tragedy of two just but opposing fronts.

The Age of Denunciation and Lack of Answers

Eastwood’s narratives often express his political vision, if not a clear denunciation of the shortcomings of public institutions, as in Million Dollar Baby. As time passes, the director seems confident enough to dare more and more, and this aspect gains increased power. However, as critic Richard Brody noted, “he has taken a step outside the world, passing from observation to judgment” in recent years. His last films don’t provide answers but pose questions, leading the audience to engage in self-analysis. The long shot of “In God we trust,” after the judge has pronounced a verdict that the audience knows is wrong, prompts reflection on the possible divergence between truth and justice and what is fair to favor.

If Justin saves himself (maybe, given a final cliffhanger), Sythe is not so lucky. His conviction represents the fall of the American Dream: he also tried his best to get a second chance, but it wasn’t enough. Much like the “Swede” in Philip Roth‘s American Pastoral or Anita’s character in West Side Story, his fate is at odds with the creed on which the American Dream lays its foundation. Sometimes, it doesn’t matter how hard you work to succeed. Sometimes, the cruelty of the world wins. And sometimes, the only real culprit is a flawed system.

Until this film, Eastwood’s previous works at least displayed a clear distinction between right and wrong. Even in a corrupt and inadequate system, people were good or evil; only sometimes, reasonable people could not help but be against the system. But this is not the world of Juror #2. All the technical choices, from the classical, elegant, and fluid editing to the tense and precise acting, align with creating a refined cinematic essay. The result is that it’s a form far from experimental. So the audience can focus on the content without any weight on understanding the form.

As it is his legacy, Juror #2 takes the audience straight to the blurry edge of its soul, into a universe that is neither white nor black, where it’s not easy to distinguish right from wrong. With this technical piece, Eastwood demonstrates the courage to leave without a solution but with the most challenging question for everyone’s morality. In Justin’s shoes, what would I have done?

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic