Jorge Amado’s Gabriela Clove and Cinnamon | The Winding Roads of Progress in Brazil

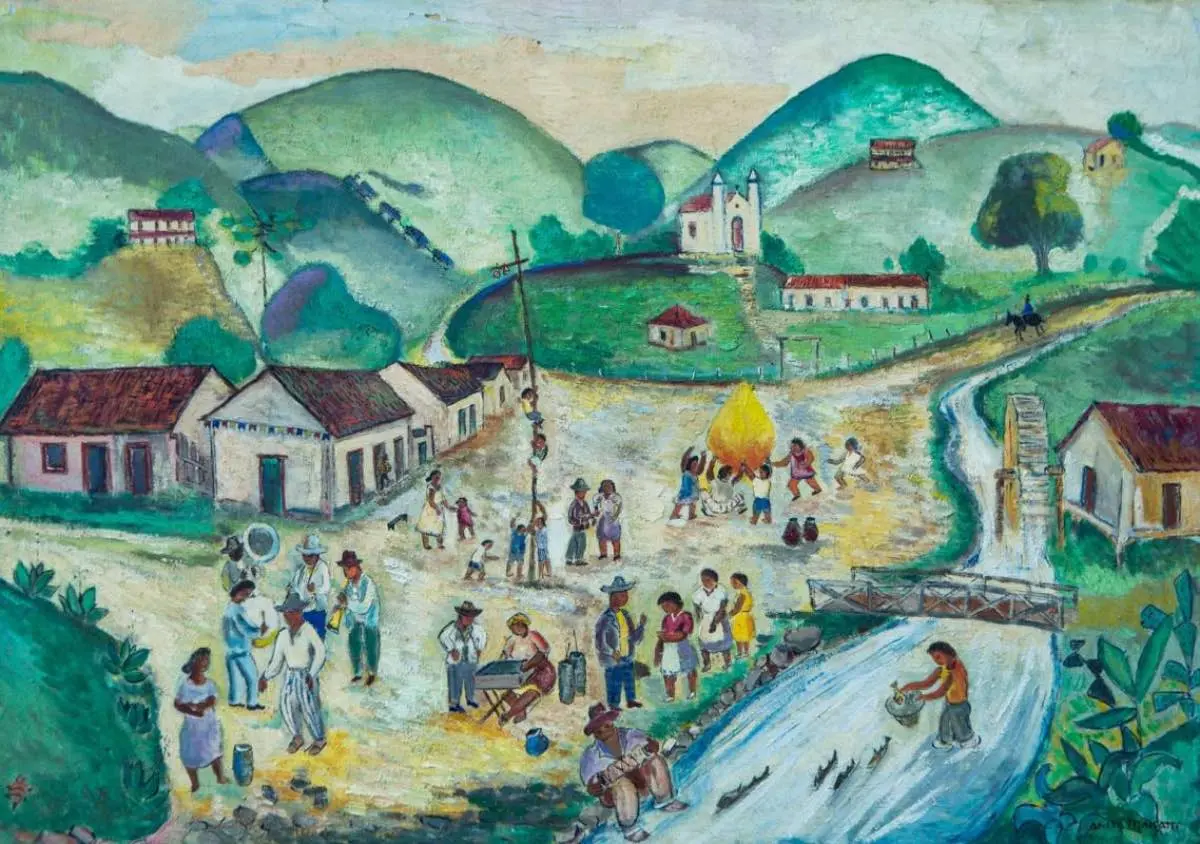

When it comes to contemporary South American literature, Jorge Amado is not a name that often comes to mind. Whether it is due to his committed communist militancy or the difficulty in categorizing his works within pre-established patterns (Pesquisa FAPESP), this oblivion involves a figure that managed to be, according to José Saramago, “the voice, the feel and the joy of Brazil”, representing “the complex heterogeneity, not only racial but also cultural, of Brazilian society”. Readers can find all these shades of color and layers of interpretation in Gabriela Clove and Cinnamon (Gabriela, cravo e canela in the original Portuguese), published in 1958 and among Amado’s most beloved and translated novels.

The plot unfolds in Ilhéus, where Amado spent his youth, and describes the love affairs, political intrigues, and massive social changes that characterized the golden age of the cocoa trade. The author creates a vivid and vibrant picture of Brazil at the dawn of its economic development, thanks to a diverse and dynamic range of characters and a fluid narrative style. At the same time, he manages to uncover the most controversial aspects of an era he experienced firsthand, as well as the social inequalities that stood in stark contrast to progress.

The novel was adapted for cinema with Gabriela (1983), featuring Marcello Mastroianni and Sônia Braga.

Love and Power in Jorge Amado’s Gabriela Clove and Cinnamon

The year is 1925, and Ilhéus, a remote seaside town of the Brazilian State of Bahia, is facing radical changes. Unprecedented rains have made local colonels’ cocoa plantations an exceptionally profitable business. Investors and traders flock from all over Brazil, and more and more climbers seek to make a fortune. Among them is Nacib Saad, the Syrian-born owner of Bar Vesuvio, who dreams of collecting enough money to purchase a plot of land and start his own fazenda.

In the meantime, though, he has to deal with a more compelling problem: his cook has suddenly resigned, leaving the bar’s kitchen unmanned. Desperate to save his business, Nacib hires Gabriela, a young woman who emigrated from the extreme poverty of the desert region of the Sertão, in search of a job. She unexpectedly turns out to be the best cook in town: her dishes and her overwhelming beauty make Bar Vesuvio the most popular meeting point in Ilhéus. With her clove scent and cinnamon-coloured smile, Gabriela receives ceaseless flatteries and proposals from the whole town, eventually becoming Nacib’s lover and, later, his wife. As the girl struggles to reconcile her free spirit with the constraints of marriage and high society, so a part of Ilhéus refuses to accept the city’s economic and social transformations.

Ilhéus and the Cocoa Boom: Brazil’s Path to Modernity

Jorge Amado’s work aligns closely with the prolific literary tradition of Latin American magical realism. Similar to Gabriel García Márquez‘s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Isabel Allende‘s The House of the Spirits, Gabriela Clove and Cinnamon tells the story of a community to portray the fate of an entire country. In fact, the romantic affair involving Gabriela and Nacib, as the author subtly declares in the book’s prelude, is essentially a narrative device to describe the development of a small town and, extensively, the process that led Brazil from colonialism to modernity. The word “progress” is a constant presence in the novel, taking on the shape of an unstoppable force that promises to lead the city towards a future of prosperity.

Day by day, the city was losing the appearance of a military camp that had defined it at the time of the land’s conquest […] The city was shining with all kinds of shop fronts, stores and warehouses were multiplying […] and then bars, cafés, nightclubs, cinemas, colleges and institutes.

Jorge Amado, Gabriela Clove and Cinnamon

However, not everyone is happy with Ilhéus’ new outline. The most conservative fazendeiros, led by old Ramiro Bastos, perceive the advancing emancipation of women and the rise of a new upper class as a direct threat to their authority, established decades earlier by force of guns. The epitome of all their fears is the young cocoa exporter Mundinho Falcão, offspring of a mighty family from Rio de Janeiro, determined to expand the city’s port to increase commercial traffic and free it from the oppressive control of the landowners. As two factions take shape, Nacib’s bar becomes the center of both political debate and daily gossip, a privileged terrace from which readers can gaze over Amado’s choral account of the city.

Such a conflict lends itself to multiple interpretations – agriculture versus commerce, citizens against country folk – but ultimately points to the archetypal pattern of generational conflict, with the old guard resisting change and envying the energy and resourcefulness of the youth.

Women, Freedom, and Desire in Amado’s Brazil

As in other works by Amado, such as 1966’s Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands, the feminine condition is a core theme of the novel, which intentionally opens with the murder of an adulterous woman by her husband. The pages of the book are filled with female figures, each representing a facet of progress towards women’s emancipation and gender equality, albeit hampered by deep-rooted customs that die hard.

There is Malvina, one of the few educated girls in Ilhéus, who refuses the future of housework and servitude that her father has planned for her. She wants to become a doctor, “living fully, freely, like the boundless sea”, without any man at her side. Glória, on the other hand, is forced to prostitute herself: supported by the jealous and irascible Colonel Coriolano Ribeiro, she lives secluded in his home, watching life pass by from her window. There are women like Ciquinha and Sinhazinha who, due to an unwritten law, pay for their husbands’ betrayal with their lives, and other women, like the Dos Reis spinster sisters, who are always ready to spread rumors about any alleged infidelity.

In this multifaceted context, Gabriela stands out as an ambiguous character. Similar to Bocca di Rosa, the fictional figure from Fabrizio De André‘s eponymous song, she makes love just for the pleasure of doing it. She loves dancing, laughing, and flirting with young men at the bar, appreciating their flatteries without ever giving in to them completely. Between the discriminations inherited from the past and the emerging gender consciousness, Gabriela is a symbol of pure freedom and irrepressible vitality, qualities that are in their own way related to Brazilian identity.

Progress and Inequality: The Unfinished Dream of Modern Brazil

Despite dating back to the 1950s, Gabriela Clove and Cinnamon remains a relevant piece of literature for its prescient take on key issues in contemporary Brazilian society. For instance, Amado seems to express, between the lines, a doubt about the actual development of his own country. In the barroom conversations of Ilhéus’ citizens, the progress experienced by the city seems to follow a linear and irreversible trajectory, supported by the thriving cocoa business and constant innovations coming from the capital. Yet, money and dancing tea parties are not enough to sweep away a past of armed conflicts and systemic discrimination. Amado discusses how the country fails to move forward, to achieve full modernity or industrialization, and to break down inequality between classes.

The difficulty of achieving a true emancipation from the legacy of the past is also evident in gender dynamics. Several public sources, such as the Brazilian Ministry of Women (whose very existence speaks volumes), describe a large and growing number of reports of violent acts against women throughout the country. Both at the time in which the novel is set and today, economic dependence significantly contributes to widening the gender gap.

Ultimately, the idea of progress that Amado proposes in Gabriela Clove and Cinnamon is complex and far from obvious, raising crucial questions about the direction his country needed – and still needs – to undertake.

Tag