Teatro Olimpico | Is the greatness of things merely an appearance?

Year

Country

Format

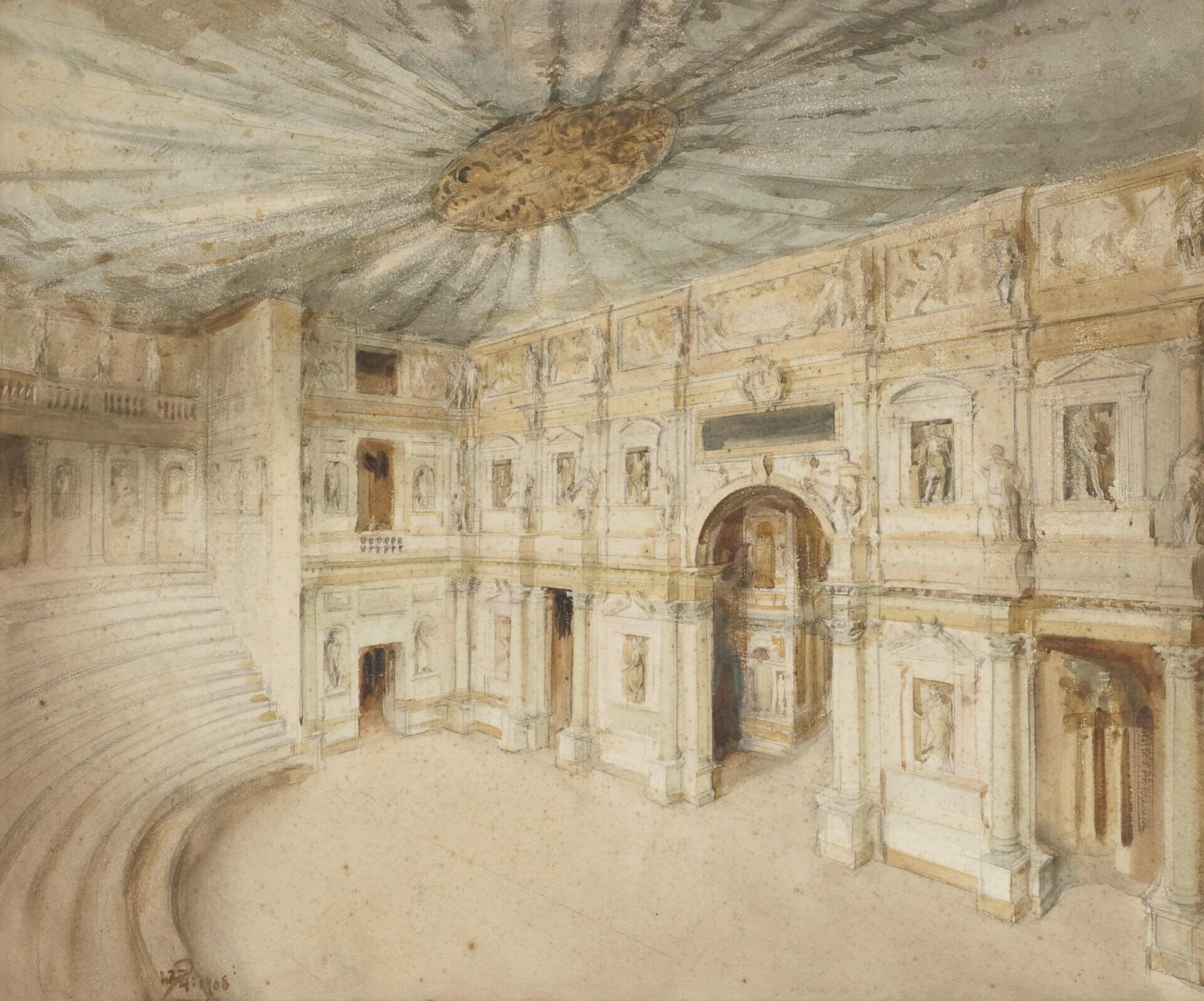

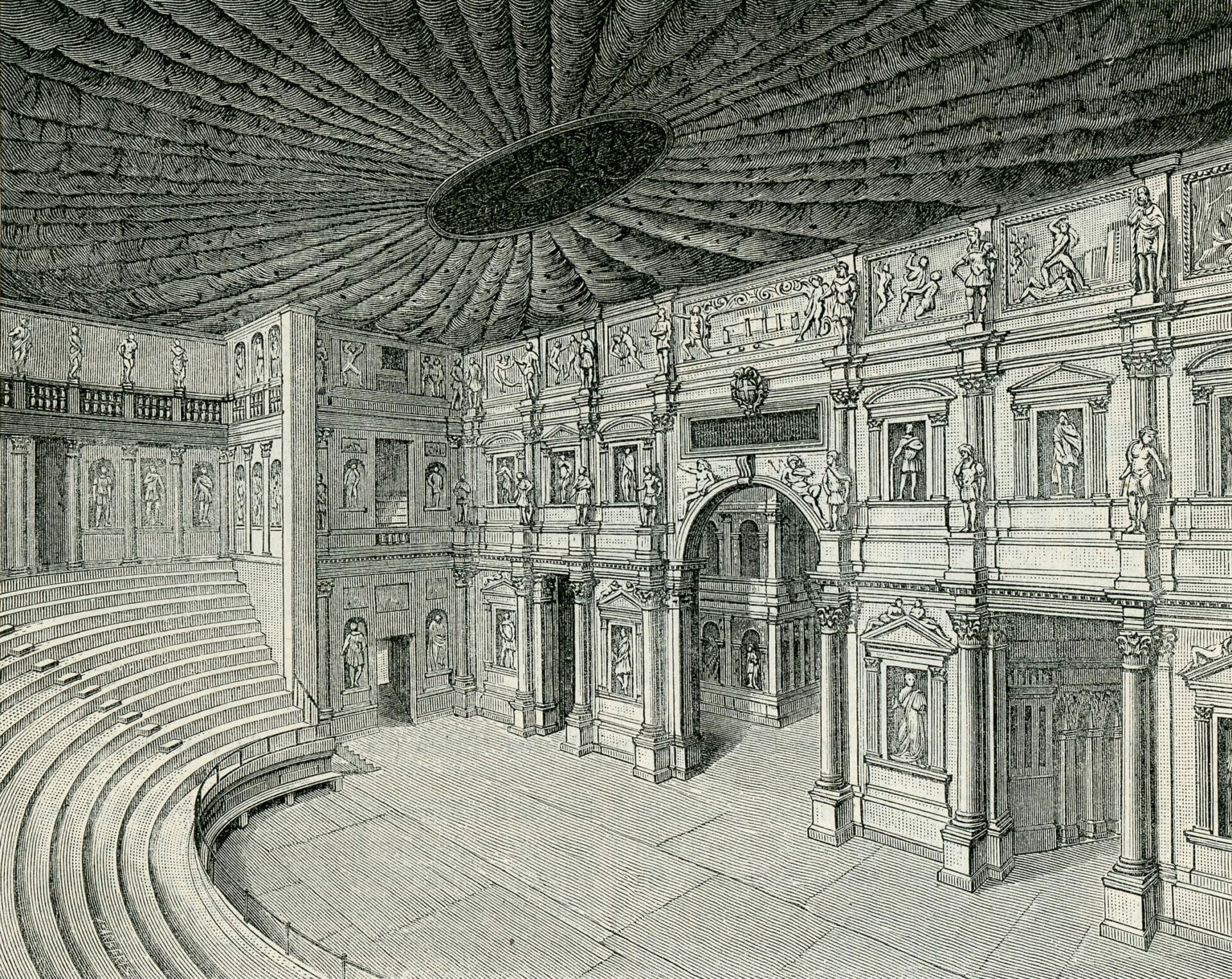

The Teatro Olimpico is a Renaissance-era theater built in the last years of the sixteenth century in the northern Italian city of Vicenza. It is the last work of the celebrated architect Andrea Palladio, who was born in Padua, which at the time of the theater’s construction in 1580, was in the then-Venetian Republic. Palladio is and was the eternal father of Palladian architecture, and the theater was his swansong. Although it wasn’t completed until four years after his death in 1580.

His farewell to art and architecture encompasses all of the influences that Palladio had drawn from studying Roman theaters’ design. Many of these influences derived from the writing of the early Roman engineer and architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. His drawings of and writings on the importance of perspective lead Leonardo da Vinci to draw his epic illustration called Vitruvian Man.

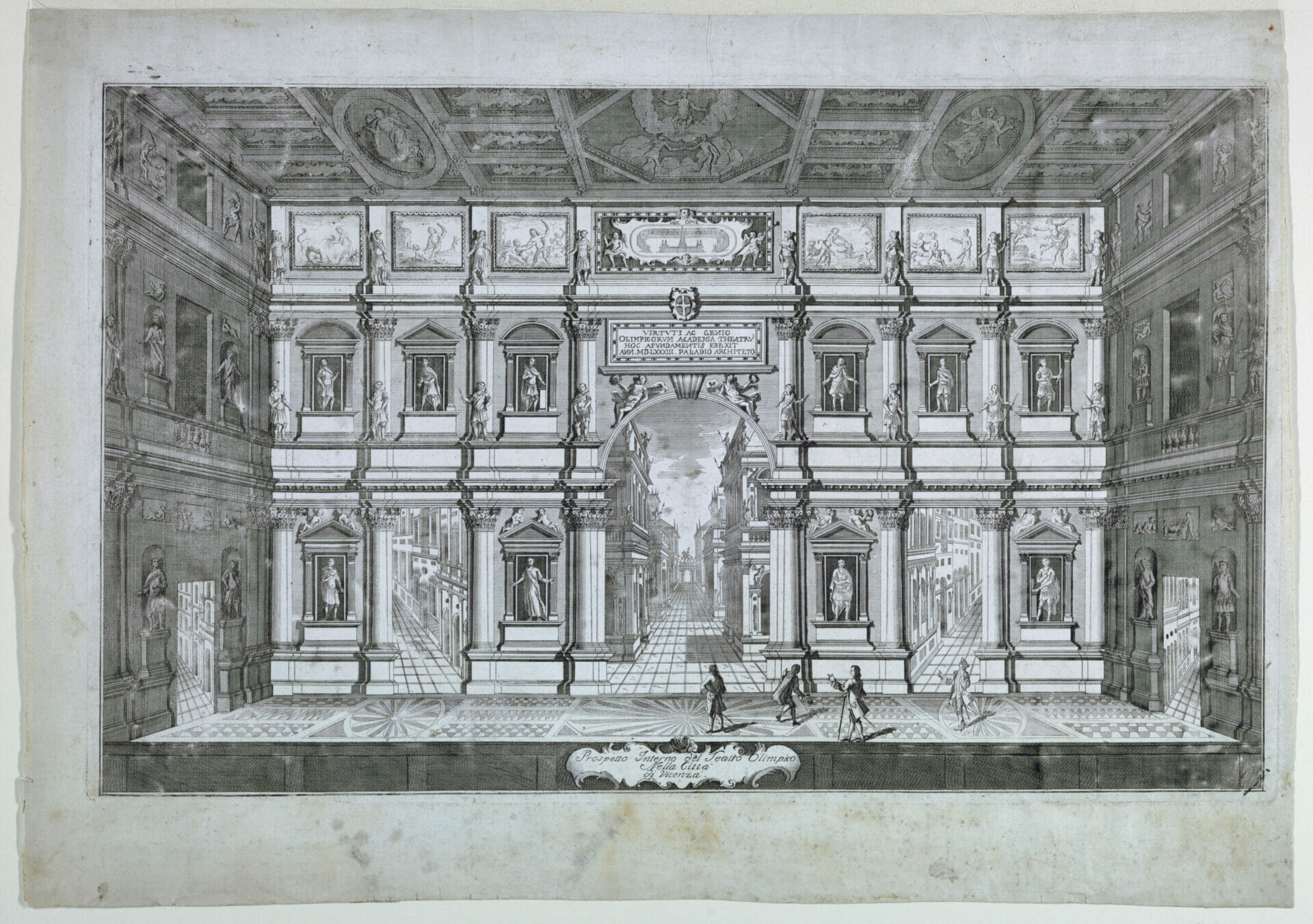

Palladio designed everything in the Teatro Olimpico, except for the scenes beyond the openings of the backdrop. The architect had planned a single perspective for the central opening and painted curtains for covering the two lateral ones.

Drawing and undrawing the curtains: the illusion of Thebes’ seven streets

The etymology of the word curtain is from the Latin word ‘cortina,’ for a veil or cloth. And it became used to delineate physical or imaginary separation between the theatre stage and the Skene, a Greek word used for the backstage area, or the backdrop. Often, nothing but a painted curtain was sufficient for illustrating performances. The Greeks, like the Romans later on, created a backdrop in the architecture of their theaters.

Vincenzo Scamozzi was a younger contemporary of Palladio, also an architect, also from the Venetian Republic. He made the most of the stage’s openings, and was one of the primary inheritors of Palladio’s influence. Scamozzi designed the scenery for the Oedipus Rex opera first performed at the inauguration of the theater in 1585.

On this occasion, Scamozzi used all of the five possible stage angles and openings, three frontal and two side ones. He used them to represent a city scene. The seven streets of Thebes, those leading to the seven gates, develop in-depth through a masterful illusion of perspective.

The installation would have been temporary and installed only for the purposes of that performance. But it turned out to be so appreciated that it was kept permanently. The Theatre in Vicenza is still in use today, as a UNESCO-listed cultural heritage site.

Forced perspective, or how to create an illusory space

The use of forced perspective is not uncommon in the history of architecture. Using optical illusion, it enables an object or person to appear closer, further away, bigger or smaller than in reality it is or they are. Like Scamozzi, Francesco Borromini used this technique to construct the Colonnade of Palazzo Spada in Rome in 1653.

In this case, Borromini gave the illusion of a colonnade thirty-five meters long by exploiting a space of slightly less than nine meters, through clever use of mathematical cunning and expertise. In the original project, a painted curtain was to depict a thick forest, sitting at the end of this colonnade. But later on, a statue of a warrior was placed there which appears in an illusory way to be life-size, but its real measurements are small.

In the grand theatre of the world, people are creators of an illusory reality that they shape as they please. The Teatro Olimpico, and the Colonnade of Palazzo Spada too, could tell of a possible underlying moral. The greatness of things in the world is only an appearance, an image, an illusion. Or is it? The fact that Palladian architecture and the Teatro Olimpico have lasted would suggest the opposite. Perhaps the last word belongs with that master of what is lasting or isn’t. The Prince of Denmark, Hamlet. For as he says, in Act I of the play that bears his name:

Is the greatness of things merely an appearance?

Tag