The sleep of reason produces monsters | When reason leaves the imagination

Artist

Year

Country

Material/Technique

Dimensions

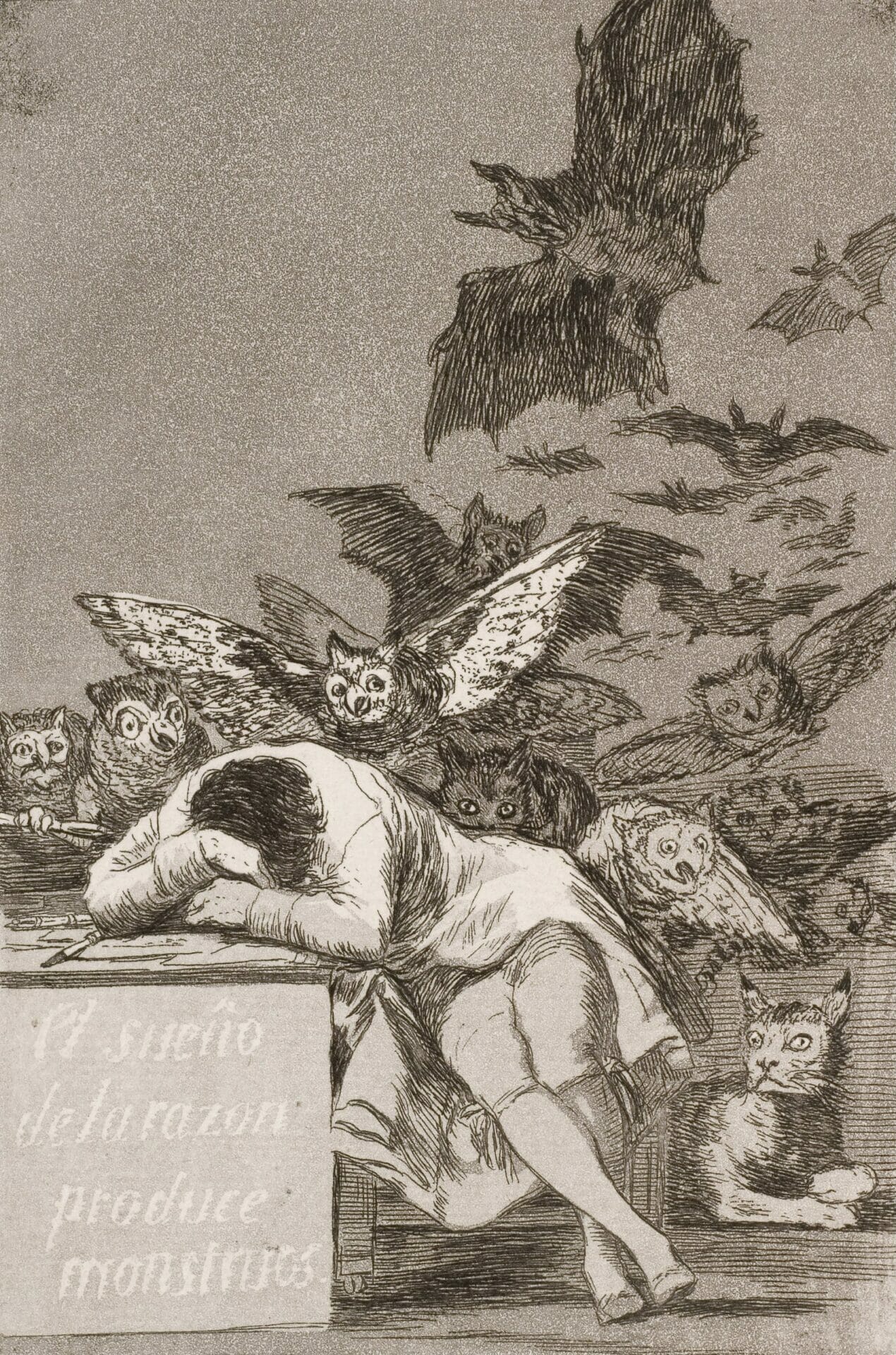

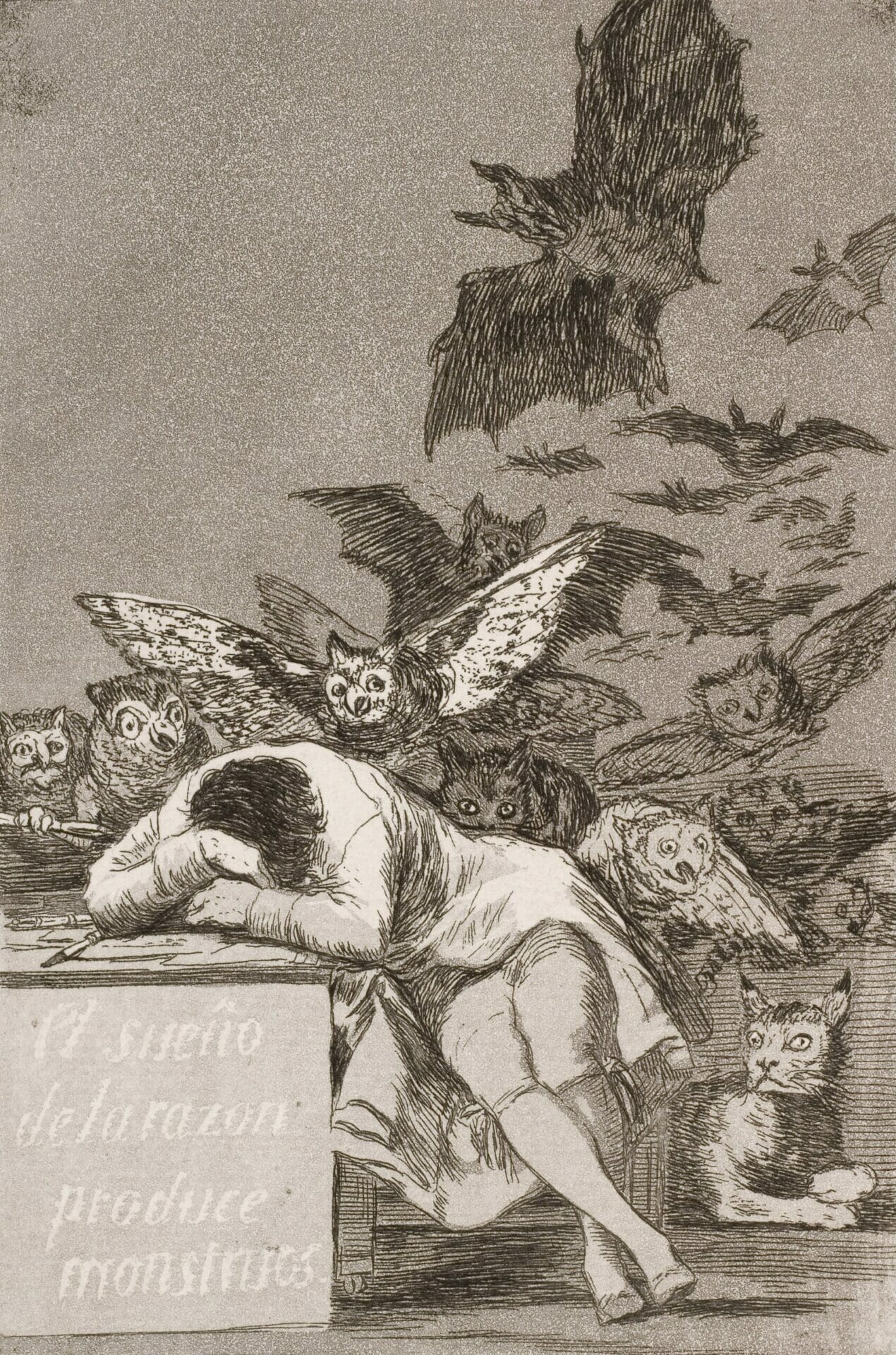

Francisco Goya, a Spanish painter, and engraver of the second half of the 1700s made The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, an etching and aquatint engraving, in 1797. This is part of a collection of eighty etchings, Los caprichos, published in 1799.

Los caprichos (The Caprices), portray human vices and miseries, as well as fantastic or grotesque subjects, in an allegorical, humorous, and satirical key.

Goya made two preparatory sketches before this panel: the first panel, untitled, depicts a figure sleeping on a desk. Four figures observe this with wide-open eyes: one of these has features similar to those of the artist.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

In the second sketch, however, there are two inscriptions, which correspond to Goya’s handwriting:

“Idioma universal. Dibujado y grabado por Francisco de Goya. Año 1797”

Universal Language. Drawn and engraved by Francisco Goya in the year 1797

“El autor soñando. Su intento solo es desterrar vulgaridades perjudiciales y perpetuar con esta obra de Caprichos, el testimonio sólido de la verdad. 1797”

The author in his sleep. His intent is to drive out harmful vulgarities and to perpetuate, with works like The Caprices, the solid testimony of truth.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

In the final drawing, the artist depicts a sleeping figure being watched by frightening creatures, his head bent over a table. Here there is an inscription:

“El sueño de la razón produce monstruos”

The sleep of reason produces monsters

As the title of the work suggests, this is divided into two parts: sleep and monsters.

With sleep, reason vanishes, and the mind of the sleeping person becomes crowded with negative figures. The mind itself, without reason, generates a nightmare composed of menacing night birds (owls) and a ferocious feline (lynx) looking toward the observer.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

In one of his three manuscripts, Commentary on Alaya kept at the Prado Museum, Goya himself explains the meaning of the work:

«La fantasía abandonada de la razón produce monstruos imposibles: unida con ella es madre de las artes y origen de las maravillas»

«Imagination abandoned by reason generates impossible monsters: united with her are the mother of the arts and the origin of wonders»

Goya, therefore, argues that if the reason does not control the imagination, the latter will go on to generate monstrous illusions. On the contrary, the moment reason watches over the imagination, a valuable resource will be created. The sinister figures portrayed in The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. This represents the mental processes present in the subconscious, which emerge only at the moment when reason rests.

The symbolism of animals

As early as the Middle Ages, nocturnal birds of prey such as owls were considered bad luck birds, “birds of ill omen”. These, in fact, are often associated with black magic, witchcraft, and the devil.

There are also positive views of these nocturnal birds of prey, such as that of ancient Greece. Here the owl is associated with the goddess Athena and is, therefore, a symbol of intelligence and wisdom. In the specific case of the owl, however, for the most part, it has a negative value.

In the Christian religion, this is in fact a symbol of bad luck, loneliness, and death.

So too, the lynx, known for its exceptional eyesight, has taken on different meanings over time, good and otherwise. In fact, for some because of its sight, it represented the constant protection of God over humans; others, however, because of its pointed ears, others associated the lynx with the Devil. In the Divine Comedy, the poet Dante Alighieri places the lynx, which he called “Lonza,” in the first canto. The lynx was one of the three beasts, along with the lion and the she-wolf, that stood in Dante’s way. Within the Commedia, these three are the allegory of the deadly sins the lynx (or Lonza) represents lust: this is because medieval bestiaries define the lynx as an animal that mates in every season since it is always in heat.

The dark manner

In 1792 a mysterious illness changed Goya’s life. This also brought numerous changes to his style and the themes treated in his works. The change in the latter, however, was also due to the political changes in Europe during those years. In director Miloš Forman‘s 2006 film Goya’s Ghosts, which stars Goya, we see how Charles IV’s accession to the throne, the French Revolution, the Napoleonic enterprise, and health problems overwhelmed the artist’s life. Thus, in 1792 Goya embraced what is the darkest, most painful, and damnable part of the human soul. Thus began the dark manner.

Goya’s first dark manner works were The Cuadritos, eleven works depicting dark, brutal, tragic scenes. The artist here chooses to paint various scenes and characters, including brigand assaults, asylum interiors, shipwrecks, and visibly confused people. In The Cuadritos, Goya illustrates what are the violent instincts and drives of the human soul. After The Cuadritos, there were Los Caprichos, and after these, The Disasters of War. In the latter group of works Goya portrayed, and denounced, the brutality and violence of the War of Independence. Finally, there were the Black Paintings, works that portray the immense triumph of evil.

In these paintings, man is powerless; he is forced to surrender in the face of the greatness and power of his melancholy and cruel fate. An example is Saturn devouring his children.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Monsters & Co. the evolution of monsters

Monsters also star in the 2001 animated film Monsters & Co. produced by Pixar Animation Studios and distributed by Buena Vista International, now Walt Disney Pictures. Directed by Pete Docter, Lee Unkrich and David Silverman and written by Andrew Stanton and Daniel Gerson, it is the fourth Pixar animated feature film; in 2002, it won an Oscar for Best Song If I Didn’t Have You, by Randy Newman. James Sullivan and Mike Wazowski are the monsters featured in the film. The two live in the town of Mostropolis, and work in the power plant, which produces electricity by turning children’s screams into electricity. The monsters enter children’s homes at night, thanks to special doors that connect the worlds of humans and monsters. However, it is not only children who are afraid of monsters.

Playing with a sharp reversal of situations, in the film the monsters fear the children as much as the children fear the monsters. Everything changes when Sullivan mistakenly brings a little girl, whom Wazowski will call Boo, into the world of the monsters. With Boo’s arrival, the two monsters realize that children are not a danger, that scaring them is not a good thing, and that it is possible to derive energy even from their laughter! The monsters thus become friends, funny figures who enter the rooms with the intention of wringing a laugh out of them. Thus Sullivan and Wazowski show monsters and humans that there is no reason to be afraid of each other.

The reason for dreams

Author Jonathan Gottschall in his 2014 book The Storytelling Instinct: How Stories Made Us Human, deals with the subject of dreams. Here, in fact, the writer talks about dreams as mysterious nighttime stories, which often feature the dreamer himself, who fights for his desires. The author, therefore, asks what is the reason why the dreamer during the night wakes up in a panic, sweating and trembling; why his brain decides to stay awake all night, and thus what is the reason for dreams.

For followers of Sigmund Freud‘s thought, dreams are encrypted messages that can only be decoded by psychoanalysis, but this solution clashes with the thinking of other scholars. One example Gottschall gives is the theory of scientist J. Allan Hobson, who calls dream interpretation a waste of time. For Nobel laureate Francis Crick, on the other hand, dreams serve to remove useless information, and therefore “dreams are for forgetting”; while for researcher Owen Flanagan, dreams serve no purpose.

The author explains that for many psychologists and psychiatrists, dreams serve as self-therapy, which helps the dreamer deal with fears and anxieties experienced while awake.

The dreams, or rather, the nightmares portrayed by Goya in his works, were nothing more than the anxieties and fears he felt while awake, during a period full of changes and health problems that disrupted the artist’s life and this prompted him to approach the dark side of the human psyche.

Tag