The Waste Land | A influences constellation in an ode to desolation

Author

Year

Format

1979 was the year of Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s film portrayal of the different psychological reactions of man to the controlled chaos of war. In this movie the elusive renegade special forces, Colonel Walter E. Kurtz reads lines from the poetry of Thomas Stearns Eliot. Seated in his cave headquarters in Cambodia, he recites the opening lines from The Hollow Men, Eliot’s 1925 poem, influenced by Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel Heart of Darkness. But during the movie, there are frequent citations to The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock (1915) and one of Eliot’s masterpieces, published in 1922. The Waste Land.

Eliot is regarded as one of the leading poets of his time: author of complex, lengthy, multiply-referential works of Modernist Poetry that read as entrancingly-labyrinthine historical, moral, and philosophical critiques of the early 20th century. And also, after nearly one hundred years, The Waste Land can stand out for its structural complexity, breadth of learning, influences, and magical use of words.

A modern Arthurian tale

Four hundred and thirty-four lines long, The Waste Land includes five sections: The Burial of the Dead, A Game of Chess, The Fire Sermon, Death by Water, and What the Thunder Said. In an inscription itself derived from Dante, the poem is dedicated to Ezra Pound. The different sections paint a poetic portrait of a world civilization in the aftermath of the horrors of World War I. At the same time, Eliot’s symbolic framework is also based on Arthurian tales and the legend of the Holy Grail and the Fisher King. He read them in two monumental essays: The Golden Bough by James Frazer (1915) and From Ritual to Romance by Jessie L. Weston (1920).

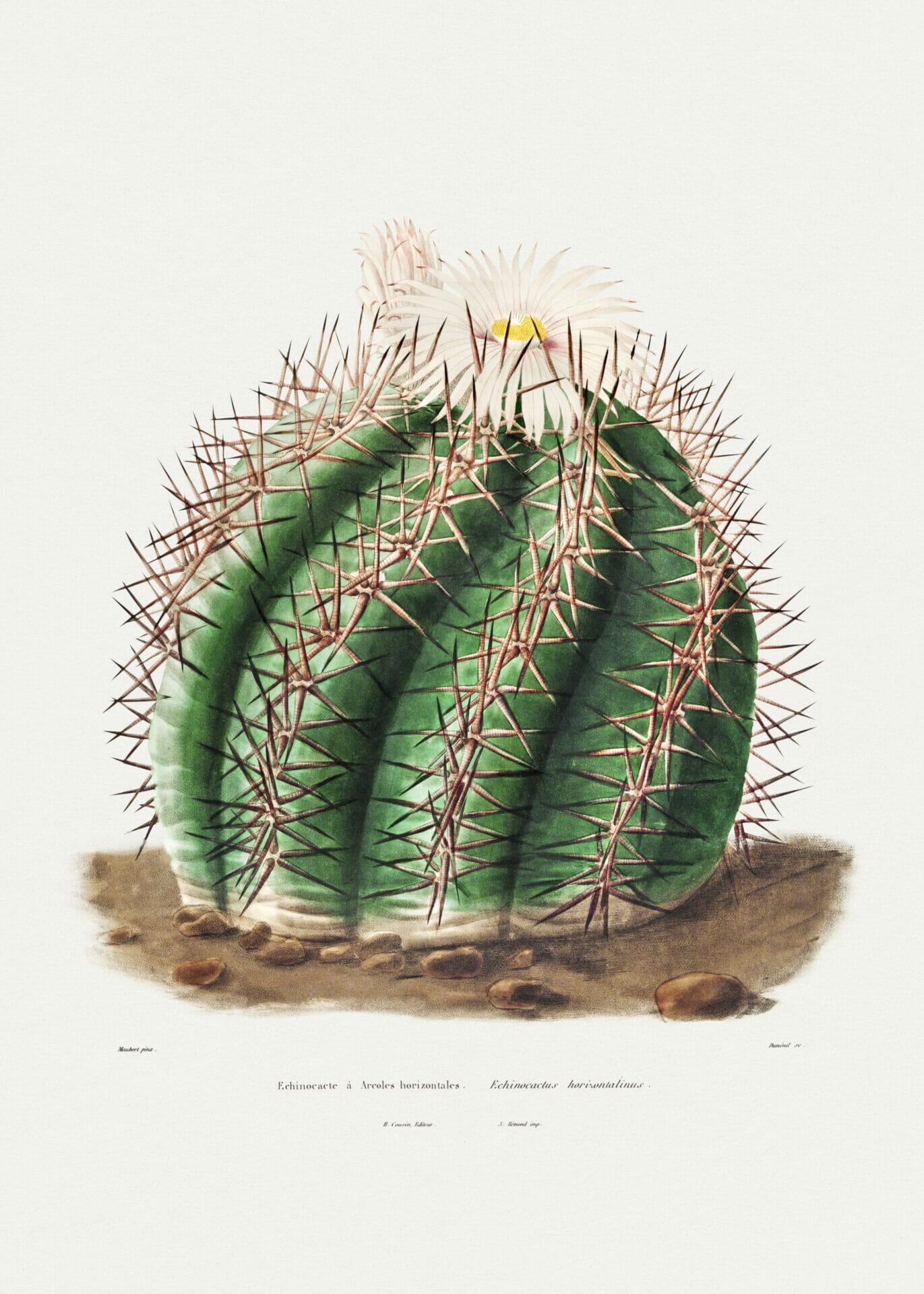

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

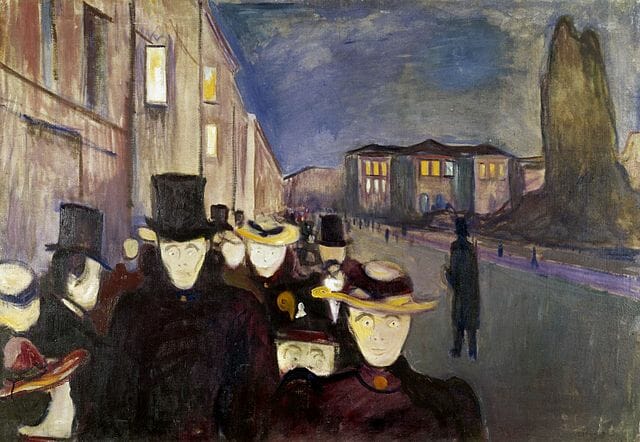

The poem swarms with anguished visions. His characters dwell in a grim, unsettling atmosphere that recalls Edvard Munch‘s last paintings.

The Waste Land is crowded with influences from Conrad, Geoffrey Chaucer, Charles Dickens, and Bram Stoker, the classics Eliot read in his youth. But Eliot’s sources are also vast, ranging from the Bible to Dante’s Divine Comedy, from Shakespeare to French symbolists, Homer’s Odyssey to the Hindu sacred text The Upanishads.

A perfect orchestra

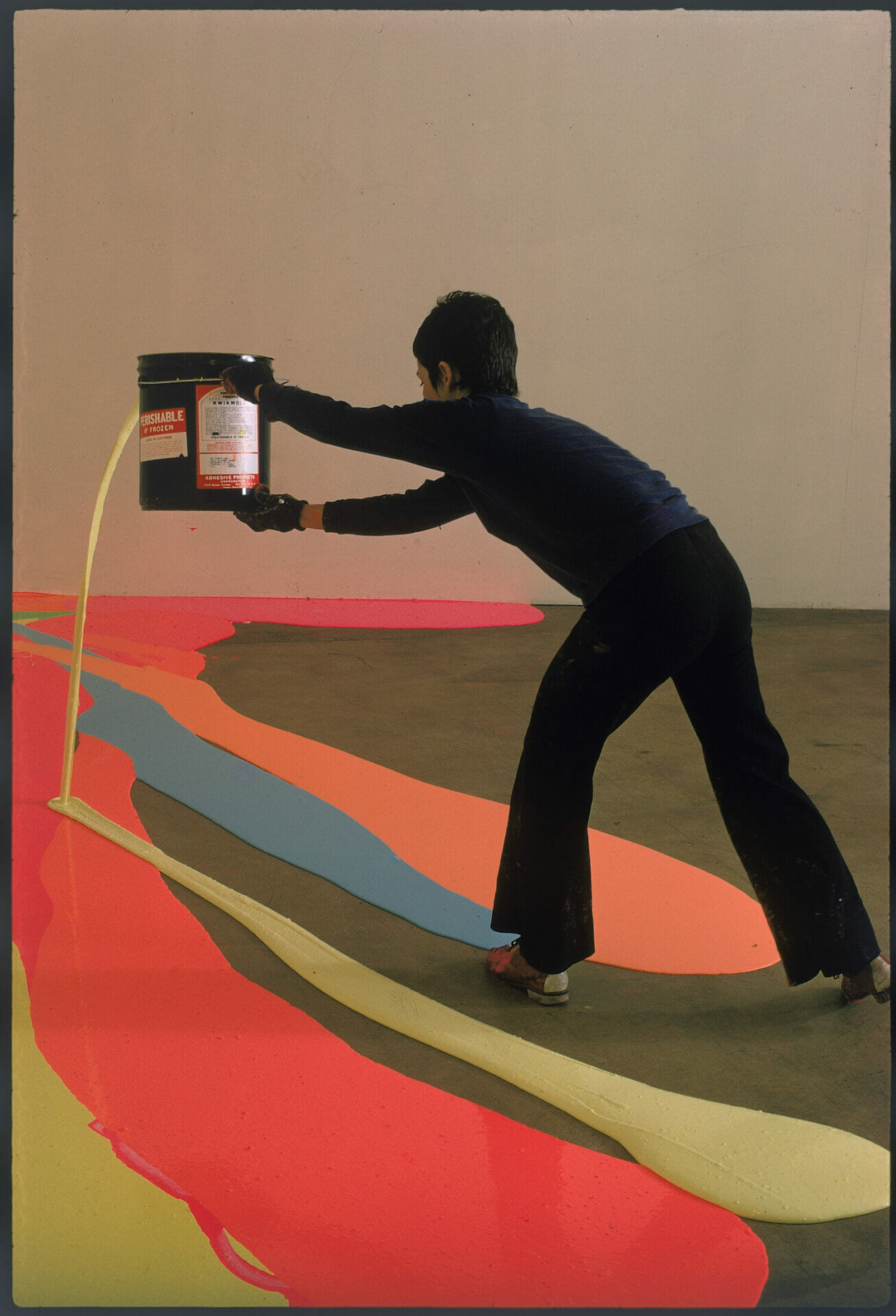

Eliot thought decay and fragmentation are the keywords of present times. To highlight these topics, he used his cultural references inserting them into scenes of ordinary modern life.

In The Burial of the Dead, for example, a crowd of anonymous workers crosses London Bridge on their way to their office. An image fuses with another from Dante’s Inferno, where the souls of the damned crowd together on the riverbank of Acheron, waiting for their journey to hell. Eliot’s alarm concerns the indifference and the paralysis with which people treat their own lives. These juxtapositions bring to the surface the meanings that lie invisibly in a world that seems to have forgotten them.

The poem appears as an orchestra of clustering voices and quotes, written in three languages, mainly English, but with French and German passages too.

In this cultural labyrinth, he uses different speech registers, frequently changing his voice from highly rhetorical to colloquial. It contains some of the most widely-regarded and quoted lines of twentieth-century poetry:

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

In 1921, when writing this poem, Eliot wrote in The Dial – a literary magazine publishing modernist writing – about Le Sacre du Printemps, a ballet with music by the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky. What impressed Eliot the most was Stravinsky’s ability to take the barbarian noises of present times, such as the rumble of the underground and the clatter of iron and steel, and turn them into a melody. Many critics noticed how this kind of method influenced Eliot’s composition.

From the narrative to the mythical method

DA

Datta: what have we given?

My friend, blood shaking my heart

The awful daring of a moment’s surrender

Which an age of prudence can never retract

By this, and this only, we have existed

While reviewing James Joyce‘s Ulysses in 1922, Eliot coined an expression that perfectly fits The Waste Land, too: mythical method. Eliot claimed that the world’s chaos did not allow for coherent narrative paths in the modern era. Therefore, the writer had to give up the simple narration and confront old archetypes, building his work as a mosaic of previous texts and influences. He shared this vision with Pound, who developed the mythical method in his poem Cantos. The Waste Land opens with a dedication: “For Ezra Pound, il miglior fabbro” (the best artisan, a quote from Dante’s Purgatory). Pound was very committed to Eliot’s poem and he was a severe editor, and The Waste Land originally started life at nearly 850 lines. Eliot, in turn, possibly over-enthralled by Pound, applied most of his cuts, corrections, and changes.

Social critique or personal relief?

The Waste Land is one of the most significant poems of 20th-century literature and influences the work of many other artists in different fields. The songs April by Deep Purple and The Cinema Show by Genesis evoke Eliot’s poem images. And Stephen King declared it was his source of inspiration for The Dark Tower saga.

Despite its evident erudition and philosophy, Eliot often declared that The Waste Land was not born as a social critique. Along with ennui and despair of the world post-World War 1, his problems and frustrations lay both with his mental stress from balancing writing with his day job and caring for a frequently sick wife, Vivienne who needed regular medical intervention.

Eliot dismissed the approving reviews of the poem as expressing the disillusionment of a generation – “I may have expressed for them their illusion of being disillusioned,” he said, “but that was not my intention.” During a conference at Harvard University, he claimed to feel flattered by the poem’s success. However, he also confessed that it was nothing but a relief from his tragedies and “a useless complaint against life.”

Tag