Politician, linguist, philosopher, and poet, Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri, better known as Dante Alighieri, explored many fields of human knowledge. In doing so, not only did he become the most prominent figure of medieval culture, but he also left a considerable heritage in Italy and all over the World.

A 700-years anniversary

Rhymes, Vita Nova, De Vulgari Eloquentia, Convivium, and the epic poem The Divine Comedy were a cultural gym for every writer. Everyone who wanted to pursue a literary career had to confront himself with these works, which were both inspiring and challenging. Francesco Petrarca, a medieval Italian writer and author of Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta, declared that he didn’t read Dante’s literary corpus because he didn’t want to suffer his influence. That was not true. Petrarca’s poetry is filled with Dantean references because Dante’s work was impossible to avoid.

Dante’s most impressive bequest was the influence on the collective imagination of future centuries. Words, scenarios, and characters left his pages and traveled in space and time. The year 2021 marks 700 years since his death in Ravenna, a small town in northeastern Italy.

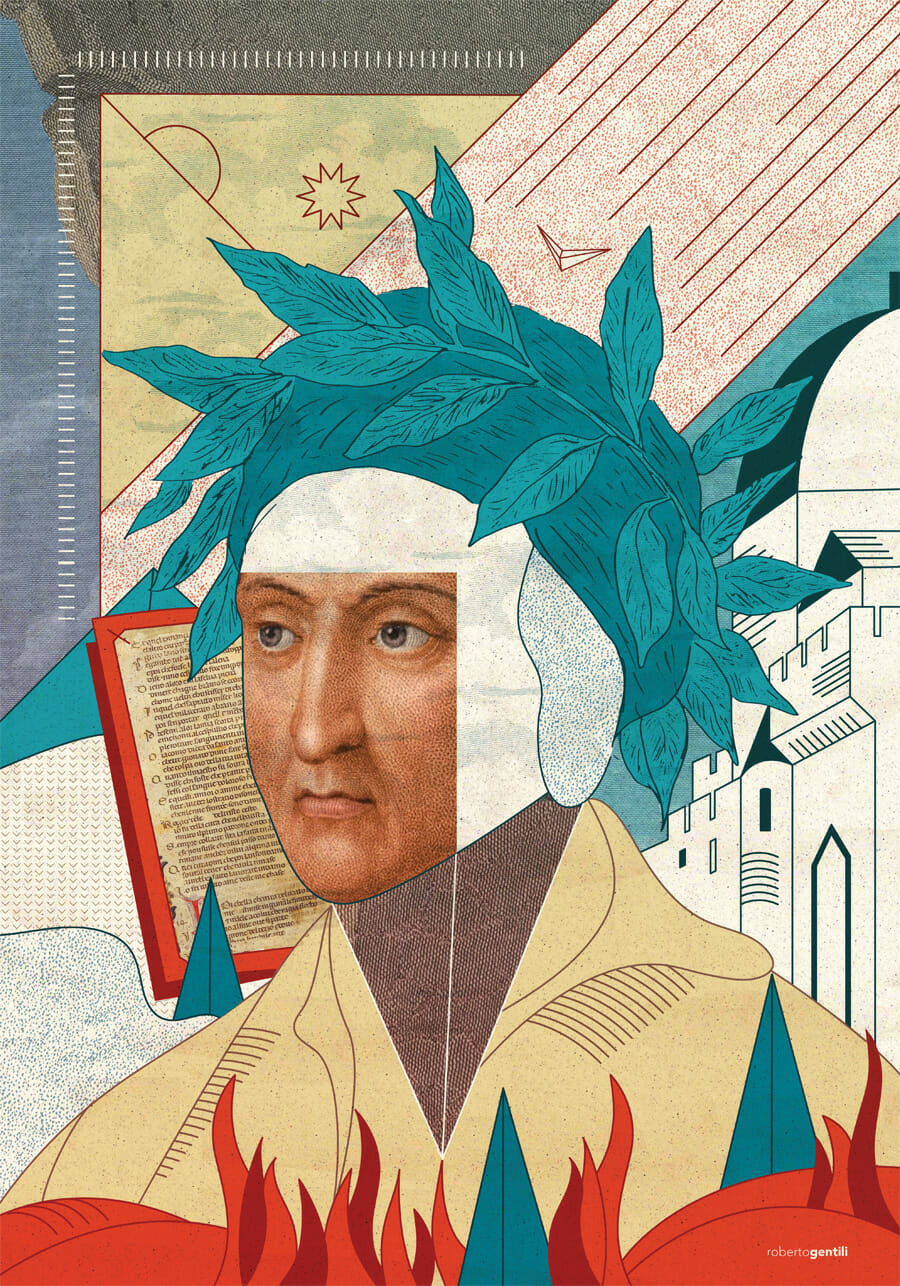

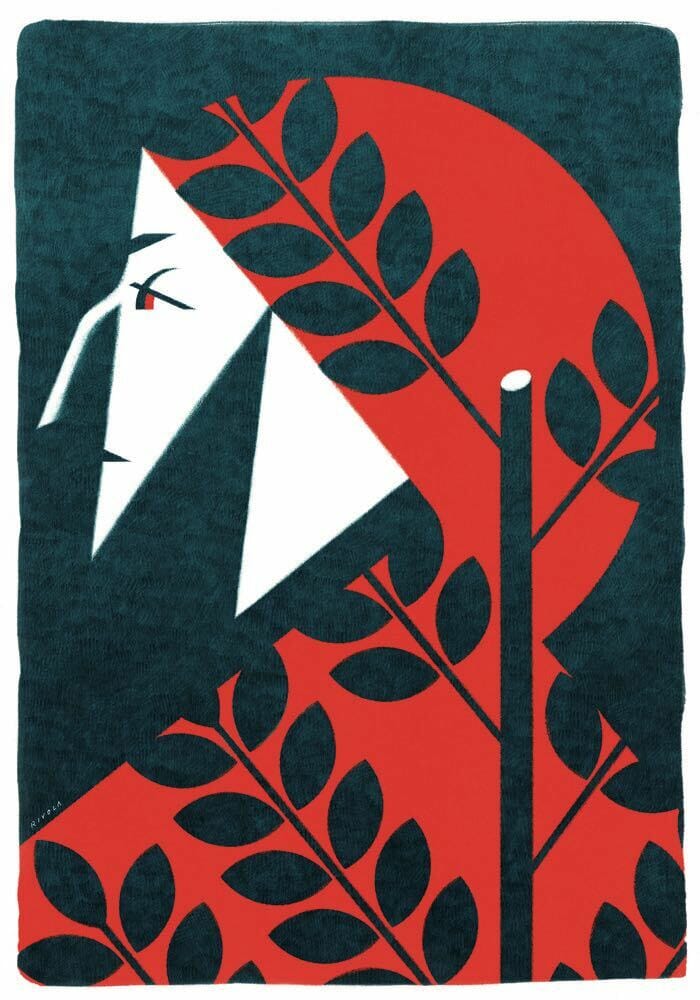

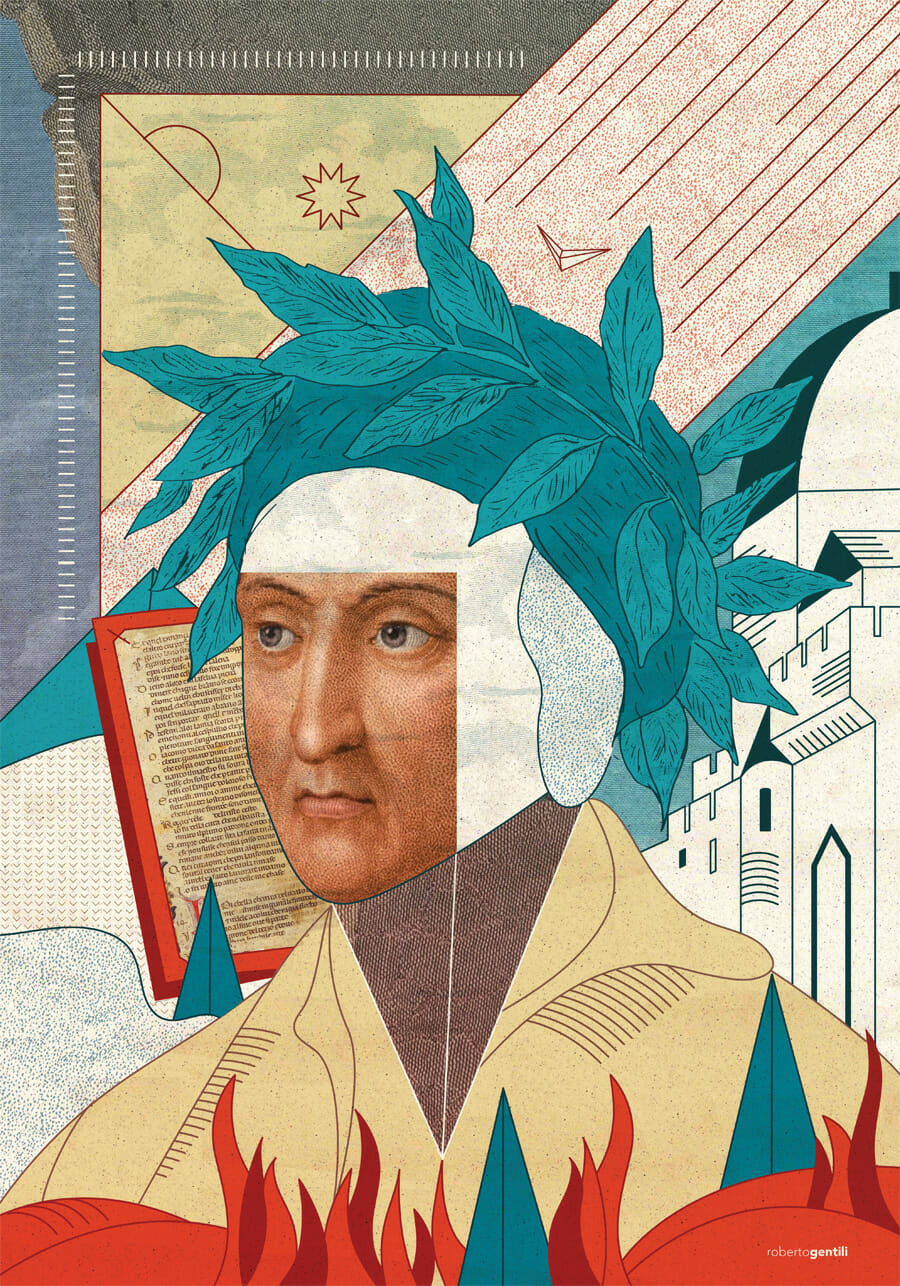

Hypercritic Poems staff wants to celebrate him with a small selection of contemporary artistic productions that follows Dante’s footprint. Choosing a collection of poems by a Nobel Prize-winner, a rap song, and a cult movie.

Dante and contemporary poetry: Louise Glück’s Vita Nova

For her eighth poetry book, in 1999, the future Nobel Prize-winner Louise Glück chose an unusual title: Vita Nova. The expression, borrowed from Dante Alighieri’s homonymous first book, means “new life” in Latin. Dante’s Vita Nova is a prosimetrum of the last decade of the thirteenth century lauding the poet’s beloved. The title refers to the change his love for Beatrice gave to his life, a rebirth opening a new season.

Louise Glück’s Vita Nova, on the contrary, concerns the end of a love story and its psychic consequences. It considers in retrospect the experience of a failed relationship and its role in the start of a new life. Despite their opposite perspectives, these two books have more in common than just the title. Not least, they are both related to the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Orpheus is the artist par excellence, capable of enchanting animals with his song. According to the myth, when Eurydice died, Orpheus had the opportunity to redeem her from the Underworld in the name of his art. His singing manages to sweeten Hades. He is willing to give him back Eurydice if he is able not to turn around to look at her. A challenge in which Orpheus fails, losing Eurydice definitively. The myth is the classical elaboration of the tragedy of the deceased beloved, a topos that had a particular fortune in the Middle Ages.

A different meaning to death

As narrated in Vita Nova, Dante also loses his young beloved. However, Dante would never ask God for Beatrice back. It would be an act of rebellion against divine providence, which he revered. Instead, the loss of Beatrice is part of his training path: her death educates him, and elevates him to higher things, to God himself. In his case, sentimental education turns into spiritual education.

Like Orpheus, Dante will be destined for a journey into the Underworld. In the Vita Nova, we can only glimpse the premise of it when the poet promises to say about Beatrice what has never been saying about anyone. It is an anticipation of Beatrice’s role as a figura Christi in the Divine Comedy. Therefore, what the Italian writer and poet Cesare Pavese makes Orpheus say in his Dialogues with Leucò can be valid for both of these catabasis heroes, Orpheus and Dante. That is, it is necessary for everyone to descend once into their own hell.

Similarly, for Louise Glück the experience of love – and to its failure – comes in the form of a catabasis. The suffering of heartbreak is her personal descent into hell. Something that, as the first poem in the book says, saved her life – but only by taking her very close to death.

Eurydice went back to hell.

What was difficult

was the travel, which,

on arrival, is forgotten.

The role of faith

In Dante’s work, the correspondence with the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is only implicit. Instead, in Glück’s Vita Nova it is explicit, as two poems in the book bear their respective names. Orpheus, in the homonym poem, is presented as a self-centered artist focused on his future permanence. Otherwise, Eurydice’s perspective brings attention back to the importance of faith in this myth.

Glück’s Eurydice is described at the moment in which the darkness of the underworld covers her again after Orpheus’ defeat. During this passage, she suffers for the lost images of earthly beauty. But finally, the loss of beauty – and death itself – results in being more bearable than the lack of faith, typical of many human lives.

only for a moment could

an image of earth’s beauty

reach her again, beauty

for which she grieved.

But to live with human faithlessness

is another matter.

Love and art had allowed Orpheus to break the laws of physics and made him almost greater than gods. But his very lack of faith makes him lose that advantage. Faith in the gods, in Eurydice, in both? In any case, for Glück’s Eurydice, it is a more unbearable betrayal than death.

Inferno becomes a rap song: Argenti vive by Caparezza

When a work of art is recognized as a classic, it is because it still has something to communicate centuries on from its first publication. Therefore, classics are helpful to describe a precise time and space using a specific writing style, and they help us understand our present when analyzed from a contemporary point of view.

This is what happens when a rapper such as Caparezza takes a character from Dante Alighieri’s Comedy and gives him the opportunity to answer back, as in the song Argenti vive, from the album Museica, 2014. As a matter of fact, his whole musical world is characterized by cultural references, as in this case, through which he deals with social themes.

Dante writes about Filippo Argenti in Canto VIII and situates him in the fifth circle of Hell, where the wrathful fight each other on the surface of the slime of the Styx. He personally knew Argenti, a Black Guelph whose family was an enemy of Dante’s. As a matter of fact, Filippo’s brother had taken Dante’s possessions after his exile from Florence, while Filippo even slapped the poet on one occasion. That’s the reason why he has to live his literary, then eternal, life among the wrathful in Dante’s Inferno. But even so, Filippo Argenti doesn’t justify his behavior and asks for mercy.

In Caparezza’s song Argenti vive, Filippo Argenti talks (rapping) to Dante using the first person and addresses him showing no regrets. On the contrary, he confirms his brutality. He begins with: “Hey there, Dante, remember me?”, as in a conversation abandoned halfway through. Dante didn’t forget him, so Caparezza uses a rhetorical question and the literal device of irony, which gradually becomes sharper through the song, so as to show sharper violence.

Così impari a rimare male di me, io non ti maledirei, ti farei del male, Alighieri!

That’ll teach you what happens when you give a bad rhyme to me:

I wouldn’t curse you, I’d harm you, Alighieri!

Rap music is full of rhetorical figures and rhyme and precise metrical patterns. In this case, there’s the alliteration of words “m,” “l,” “r;” the repetition of “male” which stands for “evil”; the etymological figura with “male” and “maledirei;” the litotes in “I wouldn’t curse you” that indicates a negation that makes the following affirmation stronger.

Moreover, he refers to the poetic world, specifically to the terza rima, the stanza Dante used in the Comedy. He does that through puns, only to show the contrast between their worlds: the poetic one and the violent one. If Dante thinks he can destroy Argenti through his terzine (terza rimas), he should imagine the damage Argenti would cause him thanks to his cinquine which means “slaps with five fingers.”

Il mondo non è dei poeti,

Il mondo è di noi prepotenti!

[…]

Se questo mondo è l’Inferno allora sappi che appartiene a Filippo Argenti!

The world is not to poets, no!

The world is to us, the domineering.

[…]

If this world is Hell, then know it belongs to Filippo Argenti!

Evil’s revenge in rhymes

As in Argenti vive, through the point of view of an arrogant being, Caparezza shows a bitter truth: not only is the evil present in the world, but also gets the better of good, whereas the arrogant people use their strength to demolish the weak and to prevail on others.

“Ye were not made to live like unto brutes”

Nice try, you’re still spitting revenge

From Phlegyas’ boat

In this part, Caparezza focuses on an aspect: how sometimes you cannot distinguish good and evil, and how they influence each other. In fact, on one side, Dante declaims high values, as in one of the most proverbial quotes of Dante’s Comedy:

Consider ye the seed from which ye sprang;

Ye were not made to love like unto brutes,

But for pursuit of virtue and of knowledge.

On the other hand, Argenti wants revenge, and he would love to see the soul falling into the slime while the other souls beat him. Therefore, he accuses Dante of not practicing what he preaches. The Comedy represents an allegorical journey through the sin present in all humans and Dante himself, so the desire for revenge can represent a crucial moment in which Dante recognizes his evil side and chooses the path of good to redeem himself.

The architecture of sins: Seven by David Fincher meets Dante’s Purgatory

Detectives William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and David Mills (Brad Pitt) are different from each other. Somerset is about to retire, he is rational, cautious, and detail-oriented. Instead, Mills is a young, passionate hothead that burns in front of injustice. In Seven (1995) by David Fincher, they find themselves investigating a series of atrocious murders committed by a mysterious serial killer.

An obese man, a prostitute, a lawyer, a drug dealer and child molester, and a model. What appears to be a random pattern, soon enough becomes clear. Each victim represents a capital sin, and their death symbolizes a macabre rite of purification. Gluttony, lust, greed, sloth, pride. Fincher distributes the sins throughout the movie, leaving the last two crimes, envy and wrath, to an enigmatic finale.

Seven is filled with literary references, but the most prominent is surely Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy. Specifically, there are two main homages to the medieval poem. The first one comes from the first cantica, Inferno (Hell), and it has to do with the murderer John Doe’s (Kevin Spacey) modus operandi. He follows the law of retaliation (contrappasso), which punishes each malefactor with suffering that has something in common with his sin.

Searching for catharsis

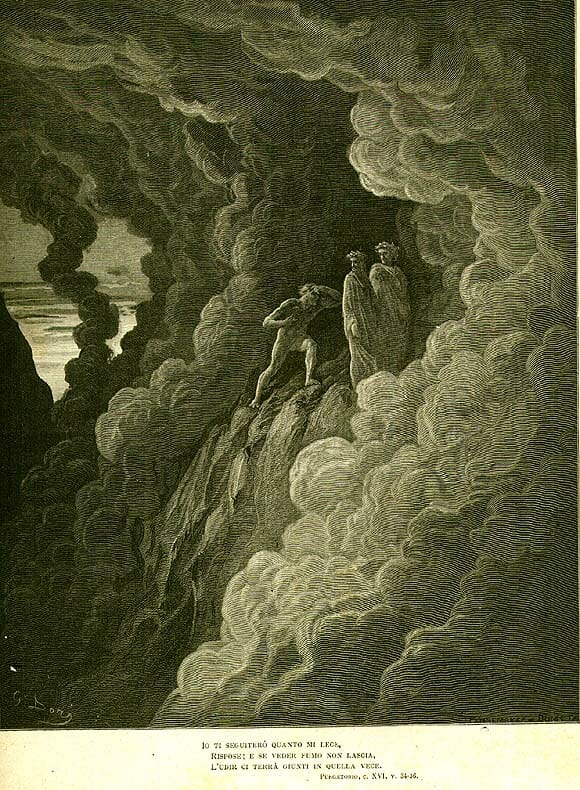

The detectives, for example, find the obese man with his hands and legs tied, sitting in his own human waste, with his face in a bowl of spaghetti. The second one concerns the religious frame of the seven capital sins. It corresponds to the division of the mountain of Purgatory in the second cantica of Dante’s poem. A medieval classification that comes from Thomas Aquinas’ philosophical theology.

At the doorstep of Purgatory, an angel puts a symbol on Dante’s forehead: the number seven and the letter “p”, which is the initial of the word “peccato” (sin, in Italian). Together with his spiritual guide Virgil, Dante moves across the seven terraces, each corresponding to a capital sin that’s being expiated. As a matter of fact, the souls of Purgatory can aim at redemption because they regretted their misdeeds at a certain point in their life. Dante ascends the mountain and meets the redeeming souls. In doing so, the number on his forehead decreases until it disappears. Listening to the stories of the sinners and witnessing the mercy of God constitutes the poet’s catharsis.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

“Long is the way, and hard, that out of hell leads up to the light,” writes Doe on a piece of paper left at one of the crime scenes. It’s a quote from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, another poetic work that owes a lot to Dante’s Comedy. Both Seven and Dante’s Purgatory show a reflection of the wounds that sin leaves in the world. This leads to a question: is redemption possible? Or is the world hopeless?

In Dante’s poem, overflowing religious fervor, the answer is in plain sight. Redemption is possible, through personal repentance and the endless generosity of God. In Seven, the answer is more complex. In the eyes of the antagonist, the world is a torrid place. Everybody turns out to be evil once they have a chance to prove it. Only death can stop this horrific destiny, a death that not even he wants to escape. But the movie does not end on a completely sour note. Detective Somerset quotes Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom The Bell Tolls: “The world is a fine place, and worth fighting for.” Then adds: “I agree with the second part.” A clarification that opens a glimmer of light: obtaining redemption, maybe, only means trying and fighting for it.

Some of the images in this article are courtesy of Bonobolabo and are on show in the Dante Plus 700 exhibition.

You can take a virtual tour of the exhibition on the official website and see other works inspired by il Sommo Poeta.