The Italian critic and author Umberto Eco always considered his bestseller The Name of the Rose overrated: “I have written six novels,” he said at a conference in Turin in 2011, “and the last five are certainly better, but according to Gresham’s law, the one that remains the most famous is always the first”.

Gresham’s Law is an economic monetary principle, which says that something seemingly of superior quality, or more valuable will eventually disappear in the face of economic commodities of the same worth.

This is something of a hard knock for a work that is considered to be one of the best-selling books ever published, shifting some fifty million copies since it publication in 1980. The book follows a murder mystery in a Benedictine monastery in north Italy in the 14th century, set around a complex trail of clues based upon semantics, hidden scripts and mysterious meanings.

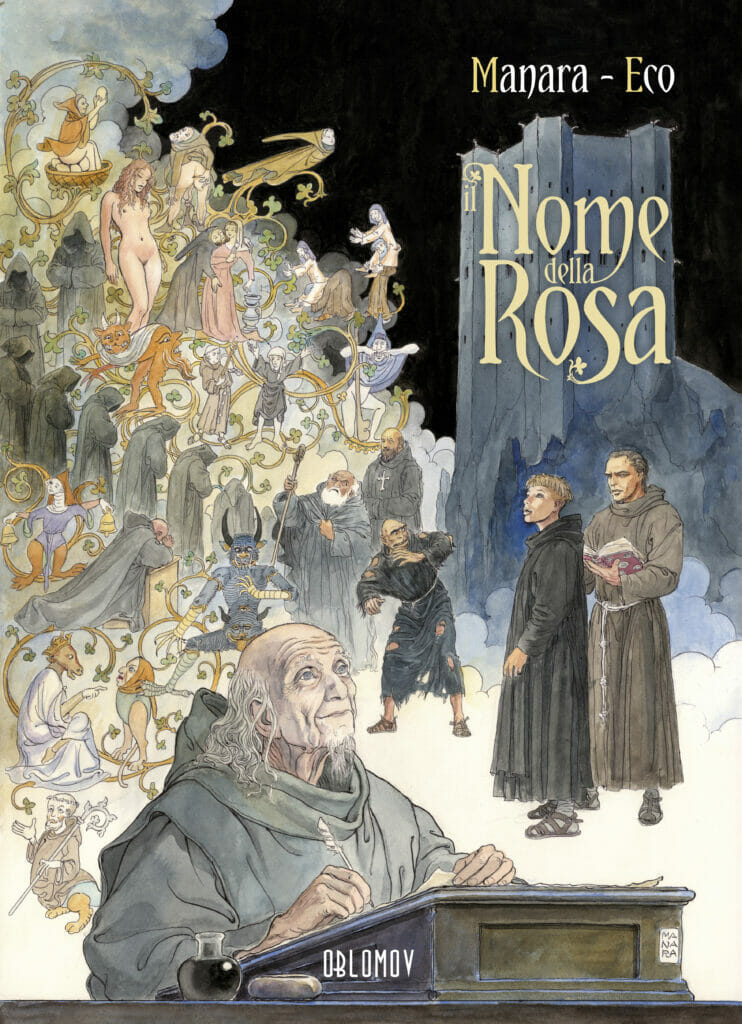

Adaptations of it have included Jean-Jacques Annaud’s 1986 movie and Giacomo Battisto’s 2019 TV series, produced by the Italian public broadcaster RAI, the first (of two) volumes of the new graphic novel “Il Nome della Rosa” was presented at Turin International Book Fair 2023, entrusted to the genius of graphic novelist Milo Manara, and published by Oblomov. Manara is an 77 year/old Italian comic book artist and writer, whose works often involve the adventures of beautiful and chic women caught up in unexpected erotic fantastical situations.

During the panel session at the fair, Manara spelled out some of the great difficulties encountered drawing and writing the graphic novels, of adapting Eco’s novel while remaining faithful to it and then counterpointing his work to the popular perception that had followed the success of Annaud’s movie, especially in Europe.

Cinema is the true enemy

With his movie, Annaud created an independent adaptation loosely inspired by the novel, inventing some scenes and changing or cutting others according to the needs of the cinematic language.

In an interview, Eco reiterated: “These are two different texts, and it is good that each has its own life. Annaud doesn’t go around giving keys to my book, and I think Annaud would mind if I went around giving keys to his film”.

Betrayal or not, when the movie was released in American theaters, it was a blunder, earning only about seven million dollars. Still, it recovered upon release in European theaters, earning ten times as much and setting a record for an Italian film only broken by Roberto Benigni’s 1997 work La vita è bella.

It’s a sign of how deeply the movie has entered our collective imagination, also thanks to Sean Connery‘s performance, as Manara confirms: “Being perfect, Scottish, and so well suited to the role”, no longer known just as James Bond, but also as the hero of the novel, the friar Guglielmo of Baskerville.

To counter the imagery of the movie and avoid conditioning, Manara says that he had to create another imagery, and the choice to characterize one of the protagonists by recalling another icon of world cinema was carefully considered. “So, I had to go back to the text, to the description of the character. He had to have an aquiline nose and a penetrating gaze”. And thus, the result of his pencil is a Guglielmo of Baskerville who resembles Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris.

The biggest challenge for Manara was not drawing men hidden under their robes but finding a worthy opponent to the myth of Connery.

Faithful to the mountain

Manara has described the adventure as “stripping the mountain with the concern of leaving the mountain”. It is not the usual quote from Michelangelo, who sees sculpture in the block and only needs to eliminate the superfluous. Manara’s work consisted of finding himself in front of a statue that had already been sculpted with complexity and having to obtain a smaller statue that would refer to the original one.

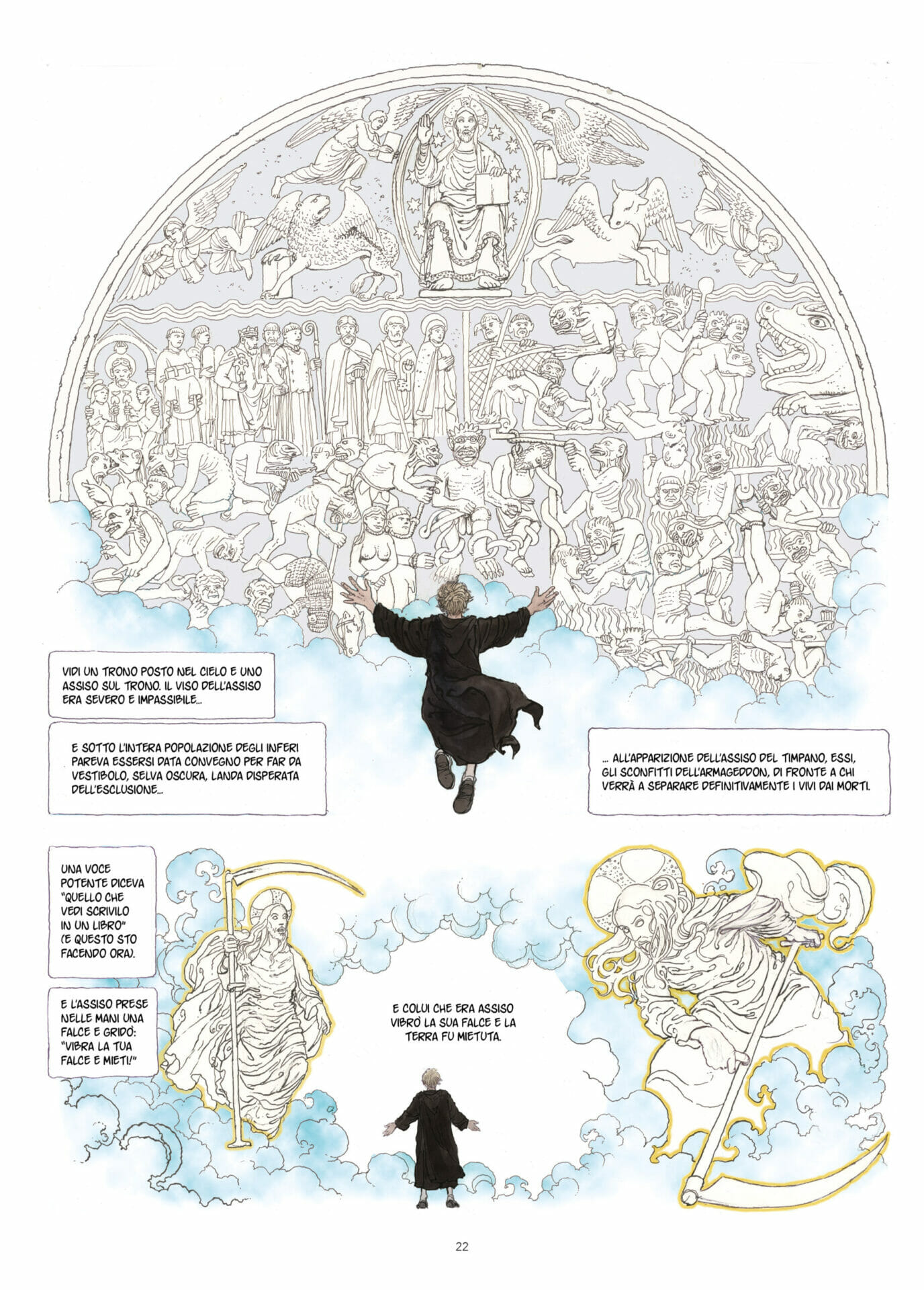

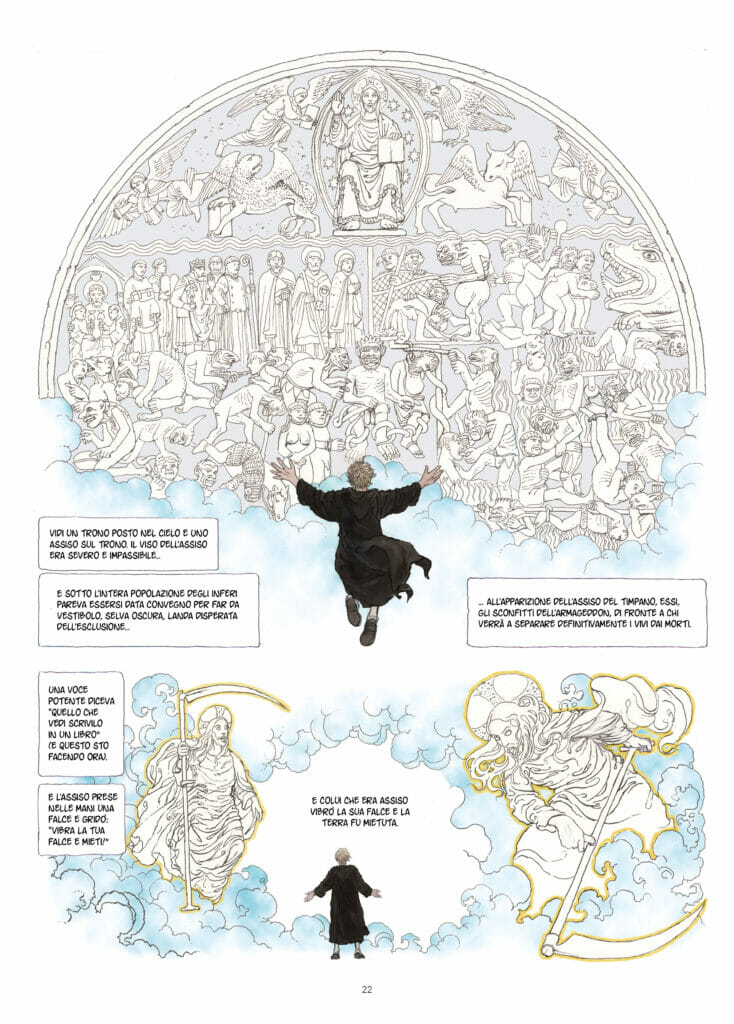

From the cover, a relevant detail can be noticed: Manara’s name is juxtaposed with Eco’s. The reason is not only editorial – as Oblomov is part of a publishing group called “La Nave di Teseo”, which holds the rights – but also a choice made by the artist himself, desiring to create a work that neither betrayed the novel nor invented from scratch, a work that through a meticulous exercise of subtraction would select what to capture within the space of a cartoon, while preserving the original text. In fact, Manara focused on fidelity to the written word, which was preserved with some cuts, and intersected three different graphic styles: sculptures, reliefs, and marginalia, which Eco quotes and describes.

The meaning lies in the details

Manara says, “I attached great importance to the marginalia, to the small decorations that accompany the illuminated figures in manuscripts. Looking at them, a different vision of the Middle Ages emerges from what we are accustomed to imagining: not a period of darkness but one dominated by an almost feverish imagination, which is inseparably connected to reality.”

From a narrative point of view, in addition to the detective story, readers follow Adso’s bildungsroman with the discovery of sensuality, the story of the Dolciniani, which seeks to focus the reader’s attention on themes such as poverty, persecuted diversity, and dissent, which remain relevant to the era in which we live.

The touch of Manara, a master in portraying female beauty, emerges in more subtle forms: Adso’s youthful dreams and the miniatures of the Marginalia enhance the erotic element, typical of the author’s poetics. But the author is keen to clarify with a smile: “I haven’t invented anything; it’s all in the original book”.

Lost in translation

Manara has made faithfulness to The Name of the Rose his strength. The film failed in this regard, but it would be incorrect to think that the graphic novel succeeded where cinema failed. Both are adaptations, translations from one language to another that, as such, always leave something behind in the process, an indecipherable gap from the original. Quoting the American poet Robert Frost: “Poetry is what gets lost in translation. It is also what is lost in the interpretation”.

The Name of the Rose is a novel that can be read on multiple levels: it presents itself as a historical detective story, but beneath the surface, it conceals a web of references to other literary works. It is a book made of other books, profound and structured, which is impossible to translate without betraying.

Different paths can be taken to adapt the story, but in the case of both the film and the graphic novel, what should be appreciated is not so much the degree of fidelity to the original work but the result of a work entrusted to the authorship of other figures in the artistic landscape who can enhance it through their own language.