Society Within | The Life and Strange Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

Author

Year

Format

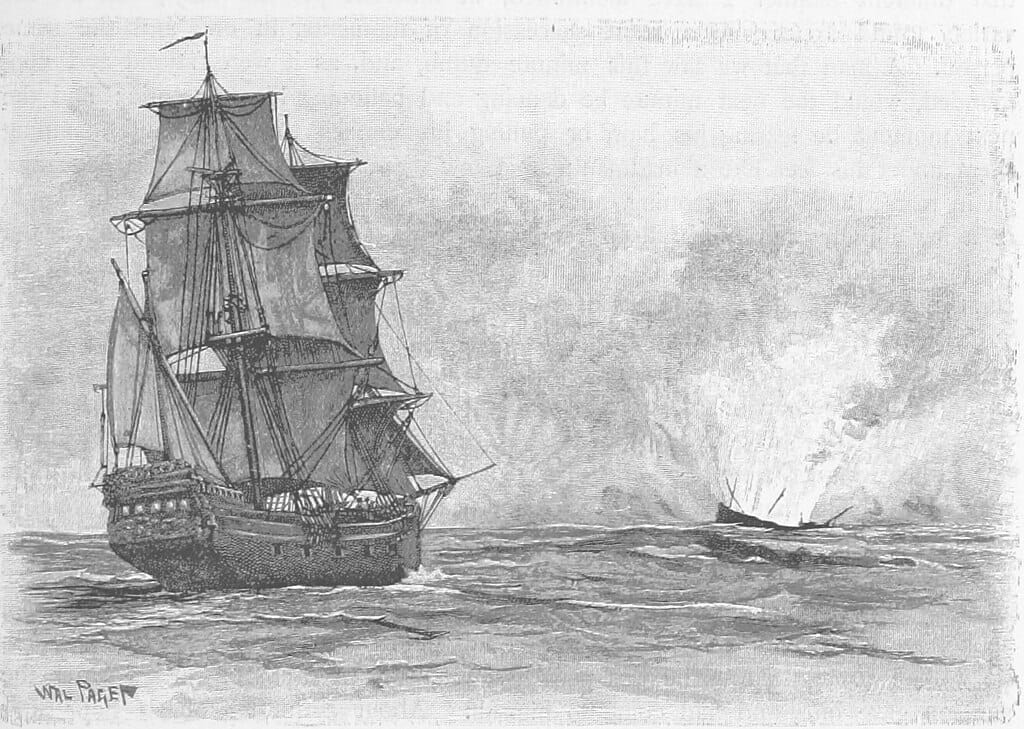

If asked what had been the luckiest day of his life, Scottish privateer Alexander Selkirk would probably have said February 2nd, 1709. On this day, after four years of isolation on a Pacific island off the coast of Chile, he was rescued by the Duke, an English privateering ship. On his return to England, Selkirk’s story became celebrated, eventually reaching the writer Daniel Defoe. Ten years later, Defoe published what was to become his masterpiece: The Life and Strange Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Among many other accomplishments, it is considered one of the first examples of the English novel.

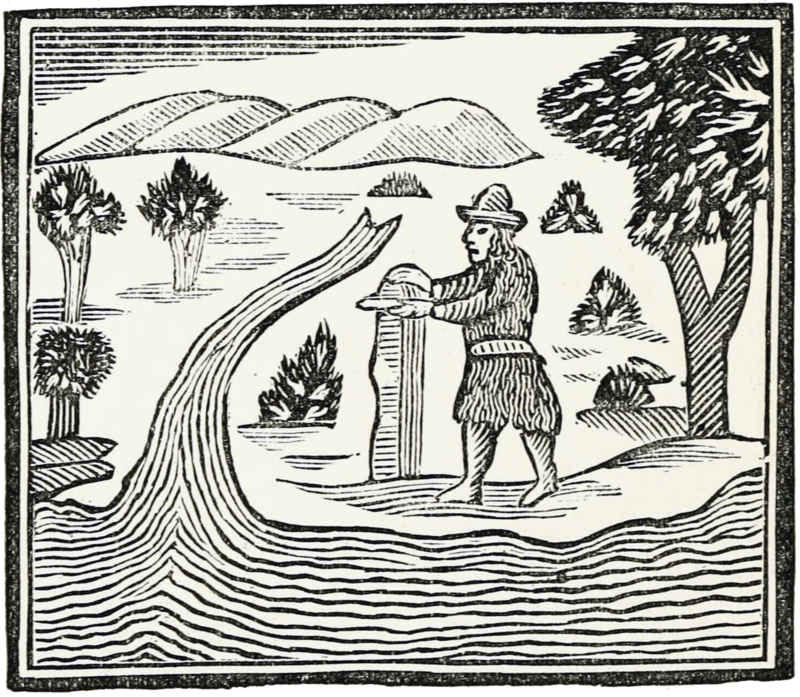

Inspired by Selkirk’s experiences, the novel tells the story of a man who spends 28 years marooned on a tropical island off Venezuela and Trinidad’s coasts. Alone, save for two cats and a dog, he builds a small shelter, adopts a parrot, grows crops, makes a calendar, and prays to God. He rescues a prisoner from some visiting cannibals and names his new companion Friday, after the day of the week. He then reads to him from the Bible and converts him to Christianity. Years later, he escapes from the island on an English ship which he saves from its mutinous crew.

A gripping story of survival, Robinson Crusoe plays out some of the most debated issues of its time, and offers a vivid portrait of the mentality of British colonists. In fact, Crusoe’s story isn’t merely a tale of solitude, but that of a social man in isolation: he might be completely alone, but he is far from being lawless.

A journey of self-discovery

Since the early 16th century, as travel-reporting genres began to flourish, Europeans started confronting themselves with the other people they came into contact with. To Illuminist and Positivist philosophers, the behavior of these so-called “savages” had become a way in which to measure and evaluate modern Europeans. This confrontation’s philosophical consequences led to a debate about the place of man within the universe, of the enlightened Christian and the noble savage.

Defoe’s interpretation of Crusoe’s solitude is that life’s experience in the state of nature is profoundly ennobling to the castaway. Only through returning to this primal condition can Crusoe come closer to God and, paradoxically enough, become a better citizen. On the other hand, he seems to nurture a desire to replicate his society on the island, calling his hut a “castle”, and referring to himself as the “king”. Thus, despite his newly discovered communion with nature, Crusoe’s mindset is still that of a colonist. In fact, while he praises his innocence, he exerts utter power over his servant Friday. Because of these contradictions, Crusoe’s adventures seem to romanticise the state of nature and deny it at the same time.

The castaway’s legacy

The Illuminist philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau was an admirer of the novel. In his renowned pedagogic treatise, Emile, or on Education, the main character Emile can read only one book: Robinson Crusoe. Rousseau believed that the education of children should not rely on books but on the first-hand experience. Therefore, in Emile’s education, reading is completely forbidden.But the tale of Crusoe is qualitatively different: while teaching him to be an autonomous man, the novel also prepares Emile to be a citizen of a commercial society.

This is just the most famous amongst countless references to Crusoe in arts and philosophy. In 1986, Nobel Prize-winner John Maxwell Coetzee published Foe, a post-colonial rewriting of the novel. It tells the story of Susan Barton, a woman who is shipwrecked on Crusoe’s island. But Crusoe’s influence goes beyond literature. Over the years, he has appeared in comics, animation, cinema and even music. In 1951, literary critic Ian Watt counted more than 700 editions, spin-offs and translations, making Crusoe one of the most popular characters in fiction. To appreciate the magnitude of his influence, one might want to consider that he gave birth to a whole genre: the so-called Robinsonade.

A social man in isolation

Some critics see Robinson Crusoe as an allegory for the establishment of modern civilization, while others understand it as a praise of economic and spiritual individualism, and still, others see it as a portrait of European colonialists’ mindset. Ultimately, though, Defoe’s take on human nature appears to be rather inclusive: for far he can be from civilization, a man is never really a savage because he is never completely alone. He might be in solitude, but he will always find ways to reproduce his fellow humans’ gaze and voice. To paraphrase an old saying, “you can take a man out of society, but you can’t take society out of a man”.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic