In the Mouth of Madness | A Storyteller's Testament

Year

Runtime

Director

Writer

Cinematographer

Production Designer

Music by

Country

Format

Genre

While not being his last or most famous film, In the Mouth of Madness can be seen as John Carpenter’s testament to his activity as a storyteller, thanks to a self-reflective nature manifested directly from the plot.

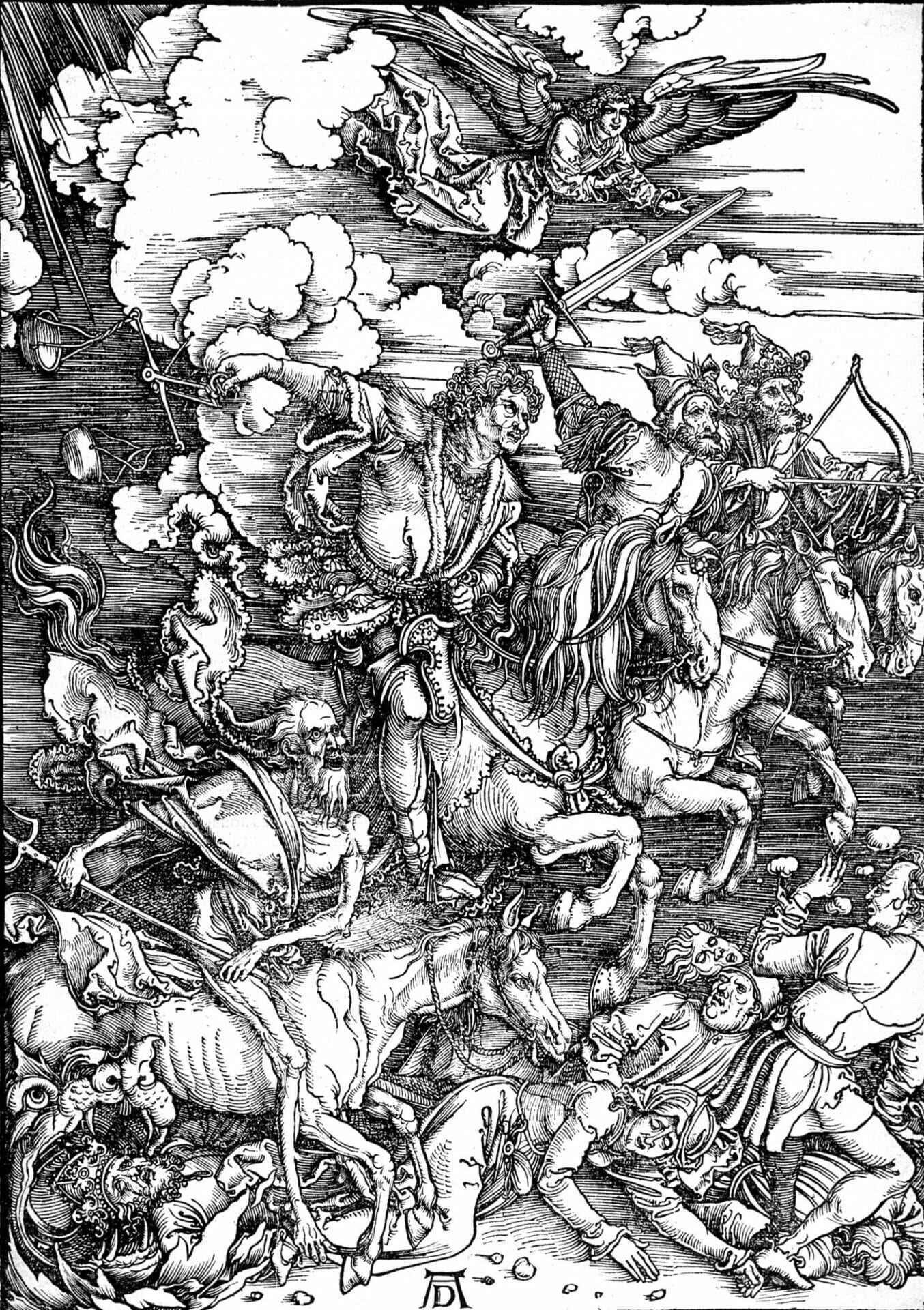

Best-selling horror writer Sutter Cane has mysteriously disappeared and with him the manuscript of his last novel, entitled In the Mouth of Madness. His publishing house hires investigator John Trent to look for him so that the highly anticipated book can finally be released worldwide. Trent will find Cane in the town of Hobb’s End, the setting for all the writer’s novels. But as his stories come to life, the line between reality and fiction, sanity and madness, becomes more and more blurred. In the Mouth of Madness is not just a book, but a gateway to Apocalypse.

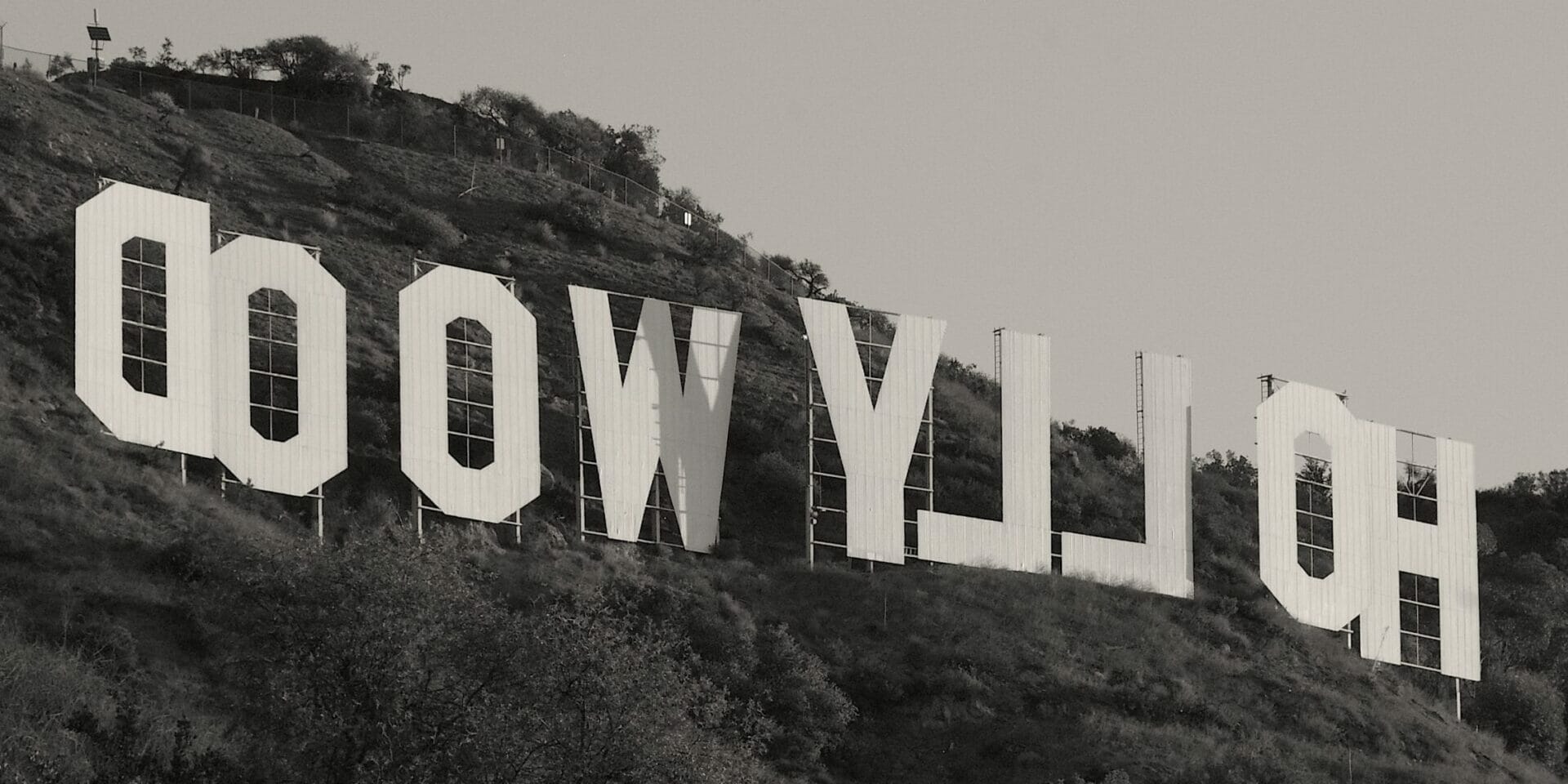

“You can forget about Stephen King.”

Sutter Cane satirically alludes to Stephen King. What Carpenter rails against is not the writer or his works (some ten years prior, he had adapted King’s novel Christine [1983]), but the massive, mindless marketing surrounding them. The film not-so-subtly argues that if, instead of King, a mephistophelian writer with a resume of novels that trigger mass hysteria showed up, he would be considered bankable and published. The commentary on consumerism and show business is evident. Stories are just other commodities to be mass-produced and sold. Apocalypse is as good a wager as any.

For Carpenter, it’s a personal matter. His career is indeed the story of a long tug of war with the film industry. Studios hired him after he broke into the mainstream with Halloween (1978), only to slowly cast him back into independent filmmaking as soon as his uncompromising views clashed with box office revenues: The Thing (1982) flopped for its nihilism; Big Trouble in Little China (1986) for parodying the white macho trope just as it was peaking in the mid-80s. With In the Mouth of Madness, Carpenter takes his revenge.

“Reality is not what it used to be.”

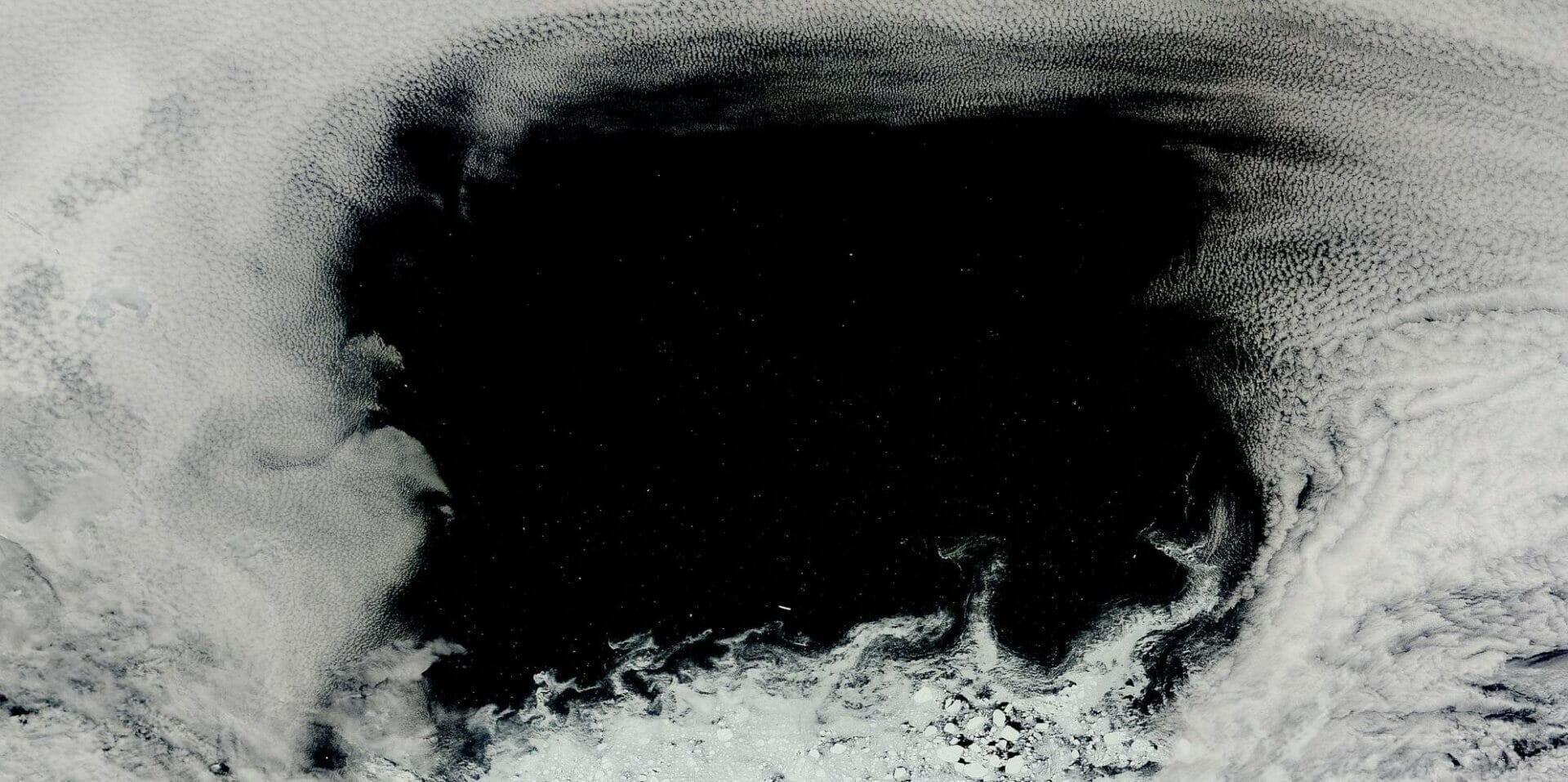

In the Mouth of Madness is the last installment, after The Thing and Prince of Darkness, in Carpenter’s “Apocalypse Trilogy”. While unrelated in terms of story, they all thematically belong to Cosmic Horror. With the series, the director ultimately pays homage to the subgenre pioneer, who’s also one of his creative fathers: H. P. Lovecraft.

Cosmic Horror is based on the idea that mankind is insignificant before the immensity of the universe. It is also impotent before the almighty alien creatures that rule it and threaten to destroy the human race in their schemes. This revelation leads Lovecraftian characters to a Nietzschean “take it or leave it” scenario. They can either enthusiastically accept the grand design or spiral into desperate madness.

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

The opening to Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu.

In the Mouth of Madness gives a new spin to all of that. It’s not just the world at stake, but reality itself. The protagonist will have to face an Evil Genius that shapes existence with his stories. Or maybe not, since the doubt about whether he has fallen into the mouth of madness or not is the backbone of all tension. The editing maximizes such ambiguity, by shaping the narrative in a Möbius’-Strip-like structure that almost foresees the later movies by David Lynch.

“This is not the ending, you haven’t read it yet.”

By adapting Cosmic Horror to meta-narrative, the film builds a monument, however pessimistic, to the power of storytelling. It warns against the everlasting risk of propaganda, whether political, corporate, or religious. Conversely, when put in the context of Carpenter’s entire filmography, In the Mouth of Madness can be seen as a storyteller’s testament.

The director’s body of work is based on the awareness of such narrative power. Stories can vivisect contemporary society. They can give a take on timeless queries. They can manipulate reality or try to see through it (as his other programmatic film They Live [1988] shows), however unpleasant that may be.

Carpenter’s horrors scare also because they refuse to reassure the viewers, and they last because they urge them to act. The rolling credits are not the ending. The real climax lies in what the viewer will do afterward.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic