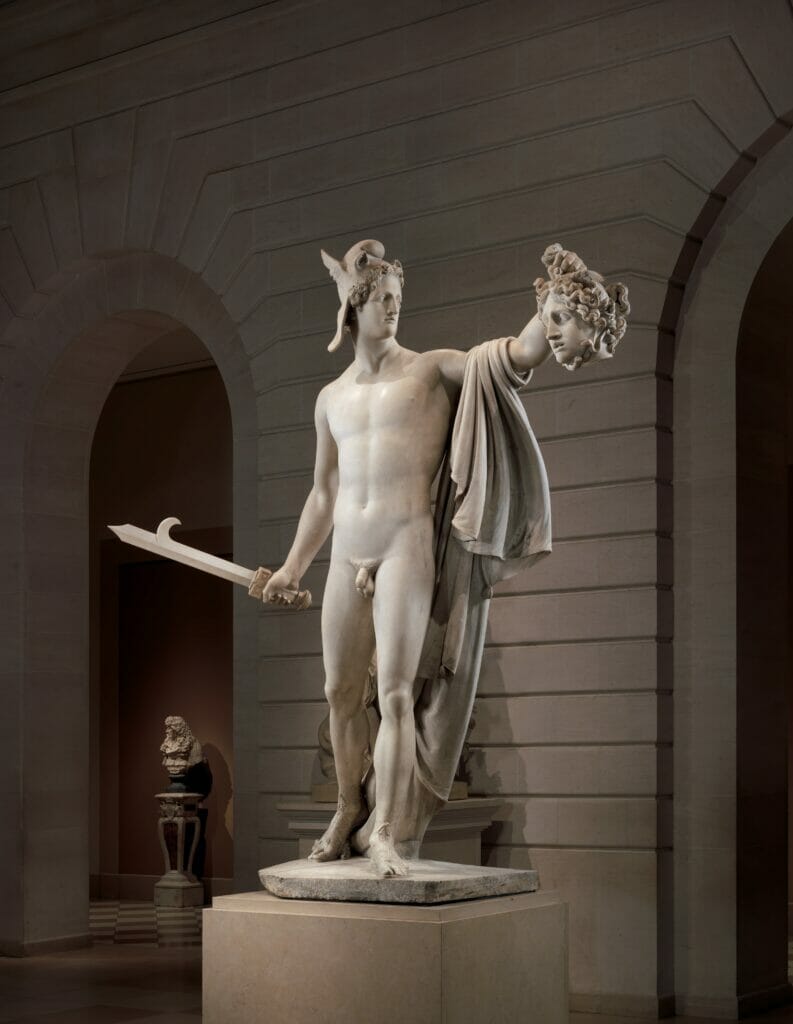

Perseus with the Head of Medusa | The different points of view of a myth

Dimensions

When Antonio Canova visited the excavations of the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 1779, the ancient Greco-Roman art fascinated the artist. This trip made an indelible impression on his approach to sculpture, making him probably the most famous and talented of the artists of the Neoclassical school. It also influenced the way he portrayed his subjects, and there are often mythological characters who appear in his works. Among the many myths sculpted by Canova is that of Perseus and Medusa, the Greek hero who decapitated the gorgon with the gaze that turned to stone any that looked at her.

Antonio Canova, and the Neoclassical style

Antonio Canova was born in Possagno in the Venetian Republic in November 1757. Aged five, he was placed in the care of his grandfather Pasino, a stonecutter by trade, who steered him to the workshop of Giuseppe Bernardi-Torretti in Pagagnano d’Asolo, and thence to Venice. Here Canova began attending the Accademia del Nudo and opened his first workshop. Among his first commissioned relevant works there are Orpheus and Eurydice (1776) and Daedalus and Icarus (1779) – both on display at the Correr Museum in Venice.

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A sculpture, the desire of many

Countess Waleria Tarnowska, the nineteenth-century Polish painter and patron of the arts, said of him:

I saw the great Canova! I saw him amidst his glory, surrounded by his masterpieces…simple, modest, he seems to ignore the fact that he has become immortal.

Determined to have at least one work by Canova, in 1804 she and her husband commissioned from the artist a marble version of Perseus with the Head of Medusa. This was not the first version of this work, as Canova had first made one in plaster in 1795, and then one in marble in 1801. This initial sculpture, the Apollo of the Belvedere, which Emperor Napoleon 1 spoliated, inspired the artist. Pope Pius VII bought the first marble version of Perseus with the Head of Medusa for 2,000 zecchini. The French tribune Onorato Duveyriez had originally commissioned the work, but the Pope decided to purchase it. He did so to compensate for the loss of the works of art the French army stole. And in this way the Perseus statue rested on the plinth that belonged to the Apollo of the Belvedere.

Although the artist had been careful to make the head of the gorgon hollow, its weight caused concern. It was thought that Perseus’ arm was unable to support the weight of Medusa’s head and that, if it gave way, the head would fall and ruin the floors of the Tarnowska Palace in Dzików. So when the artist sent the marble statue, he also sent a plaster copy of Medusa’s head by itself. So the artist allowed the Counts to replace the head with this lighter plaster version. If they had opted for this solution, the counts could have reused the marble head as a ghostly lantern, and so it is therefore probable that Canova finished Medusa’s head so that it could be placed on a flat surface.

For this reason, the iconography of Canova’s head differs from those reproduced by other artists in that it does not appear dripping and bloody. If one thinks of the one Caravaggio depicted in the work Shield with the Head of Medusa or the head of Medusa supporting Benvenuto Cellini‘s bronze Perseus, one can see that these are dripping with blood. Like Canova’s Perseus, Cellini’s Perseus also has special features. Behind the nape of Perseus’ neck hides another work of art, the artist’s self-portrait.

Photos by Annamaria Russo

In the end, the Tarnowskas decided not to change the statue. They did not replace the plaster head with a marble one but preferred to change the location of the statue, instead. So the countess placed the statue on her father’s landed estate in Horochów. Today the work is located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where the famous Met Gala occurs.

The myth of Perseus, the birth of a hero

Perseus was the son of Danae, who was the only daughter of Ancrisius and Aganippe, king and queen of Argos. Worried, King Ancrisius consulted the Oracle of Delphi to know what fate awaited his kingdom, but it gave him an unexpected answer. Danae would have a son who would achieve glory but would kill him. So Ancrisius locked his daughter in a tower, hoping to circumvent the prophecy. Nevertheless, Danae conceived a son with the god Zeus. He, in the form of a shower of gold, managed to enter the tower through a crack in the roof. Frightened by the Oracle, the king locked Danae and the baby Perseus in a wooden box and abandoned them in the sea. The chest reached the island of Seriphus, where a fisherman rescued it. He was a Ditti, the brother of the overbearing king of the island, Polidette. As the years passed, Polidette fell in love with Danae. The king tried to convince her to marry him, but Danae never returned his love.

Perseus and Medusa, heroes and monsters

King Polidette wanted to drive Perseus away, so he devised a plan and announced that he wanted to get married to Hippodamia. He wanted as a wedding gift a horse from each of the guests. Perseus, mortified that he did not own a horse, promised Polidette whatever he wanted. He made this promise to him on the condition that he would no longer seduce his mother Danae. So Polidette asked Perseus to bring him as a gift the head of one of the three Gorgons, Medusa.

To accomplish this feat, the boy had to obtain three things: the winged sandals of Mercury (Hermes) to move faster, the kibisis, a magic bag in which to put the severed head of the Gorgon and the kunè, Pluto’s (Hades) helmet that makes one invisible. The goddess Athena had also given Perseus a shield, shining like a mirror, so that he could only look at Medusa through her reflection. The god Vulcan (Hephaestus), on the other hand, gave him a diamond sickle with which to cut off Medusa’s head.

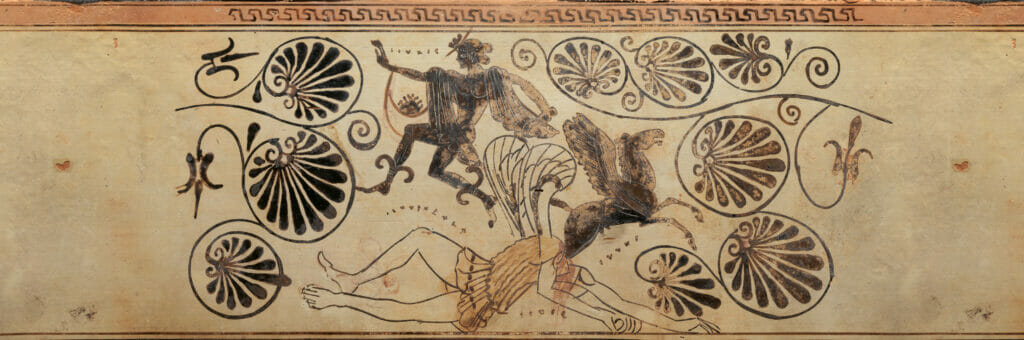

To obtain the three objects Perseus had to find the Stygian Nymphs. They lived in a place known only to the Graeae, so he bargained with them and obtained from the Nymphs the three objects. Then, Perseus headed for the land of the Hyperboreans. In this place, nature is cold, a sinister grey colour and the forest into which Perseus set out was full of people who Medusa had petrified. Once he found the gorgon, the boy managed to defeat her thanks to the objects he obtained. When he decapitated her, a Pegasus and Chrysaor, a giant son of Medusa, sprang from Medusa’s neck. Medusa’s blood also had magical properties. That which dripped from the left vein was a deadly poison, while that which leaked from the right vein was an antidote capable of resurrecting the dead.

The myth of Medusa, the redemption of the monster

Medusa is one of the three Gorgon sisters, whom in the most ancient representations artists depicted as monstrous women. They had golden wings, bronze hands and snakes for hair. Their faces were chubby, sometimes also covered by a short beard, their mouths wide and with large fangs. Over time, these mythological figures became embellished, but always keeping the characteristic snakes in place of hair.

According to some authors such as Ovid, Hesiod and Apollodorus, Medusa was not always a monster, quite the contrary. According to these authors, Medusa was a beautiful maiden that the goddess Athena transformed as a punishment. Medusa is said to have lain with Poseidon in one of the temples dedicated to the goddess. In some versions of the tale, it is said that Medusa’s beauty abducted Poseidon and that the god, to anger Athena, raped the maiden in her temple. However, Athena did not punish Poseidon, but Medusa. The goddess gave her the appearance of a monster that would turn anyone who looked into her eyes into stone. Other versions of the myth, however, say that the goddess would have turned the maiden only because she had dared to compete with her in beauty.

In 2008, the artist Luciano Garbati created his version of the Perseus and Medusa myth Medusa with the Head of Perseus. In this sculpture, the artist turns the myth upside down, representing the gorgon holding the head of Perseus. Garbati gives voice to Medusa, who has always been called a monster, giving this character a different ending to the traditional one also represented by Canova. Redemption for a woman who not only suffered violence but also incurred the unjust wrath of a goddess.

The modern version of an ancient myth

There are many references to the mythological figure of Medusa in Pop culture. From video games, such as Assassin’s Creed Odyssey and God of War, where the gorgon is one of the enemies to be defeated, to books such as Athena’s Child where author Hannah Lynn proposes a version of the Medusa myth different from the one we all know. There is also no shortage of references in TV series, such as Ajax, the gorgon boy from Tim Burton‘s Wednesday series. Medusa, however, is also one of the characters in Percy Jackson and the Olympian Gods, a collection of five fantasy books by Rick Riordan. The eponymous films The Lightning Thief (2010) and The Sea of Monsters (2013) were inspired by these. Riordan himself also announced the release of a TV series in 2024 on the Disney+ platform, which would be inspired by the first book The Lightning Thief.

In the movie Percy Jackson and the Olympian Gods, Thief of Lightning (2010), Uma Thurman plays the role of Medusa. If in Kill Bill the actress plays the role of a woman who takes revenge for the evil done to her by killing and beheading, in Percy Jackson it is she who suffers this same fate. Just as in the myth, the protagonist Percy, like the Greek hero of the same name, decapitates the gorgon, but a smartphone plays a key role in this scene. This acts as a mirror, a black mirror, a modern version of the shield that the goddess Athena gave to Perseus so that he could kill Medusa by looking only at her reflection.

The myth of Perseus and Medusa over the centuries has been interpreted in a different ways by artists. The public was able to see different facets of these two mythological characters, and how each artist tells the same story in different ways, each with their own authorial characteristic. Faced with all these different versions of the same myth, from Canova’s classic, Garbati’s redemption, to finish with Rionard’s modern one, we cannot but ask ourselves: who is the villain?

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic