A Myth of Devotion | Louise Glück on love and oppression

Author

Year

Format

A Myth of Devotion by Louise Glück belongs to a centuries-old tradition of poetic reinterpretations of myths. Many characters of Greek mythology reside in the lines of famous poets. Among the others, Francesco Petrarca used Apollo and Daphne’s story in his Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta to talk about his unreciprocated love for Laura; Alfred Tennyson wrote Ulysses to praise the tireless search for knowledge; Wisława Szymborska, in her Monologue for Cassandra, exposes a dilemma on whether settling for the immediate or struggling for the future. In A Myth of Devotion, Glück uses a similar scheme. She takes a famous archetype to find a new point of view on an old existential theme: love.

Persephone: a guide for the underworld

The mythological setting is already in the title of the collection that contains A Myth of Devotion, Averno. Glück published it in 2006, when she had already won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry (1993) and gained the title of Poet Laureate in the USA (2003). The epigraph introduces the reader to the world that builds Glück’s lines: “Averno. Ancient name Avernus. A small crater lake, ten miles west from Naples, Italy; regarded by the ancient Romans as the entrance to the underworld”.

For this journey to the underworld, a metaphor for the hell everyone experiences in life, Glück chose a specific guide: Persephone. She appears in four poems: Persephone the Wanderer (I), A Myth of Innocence, A Myth of Devotion, and Persephone the Wanderer (II).

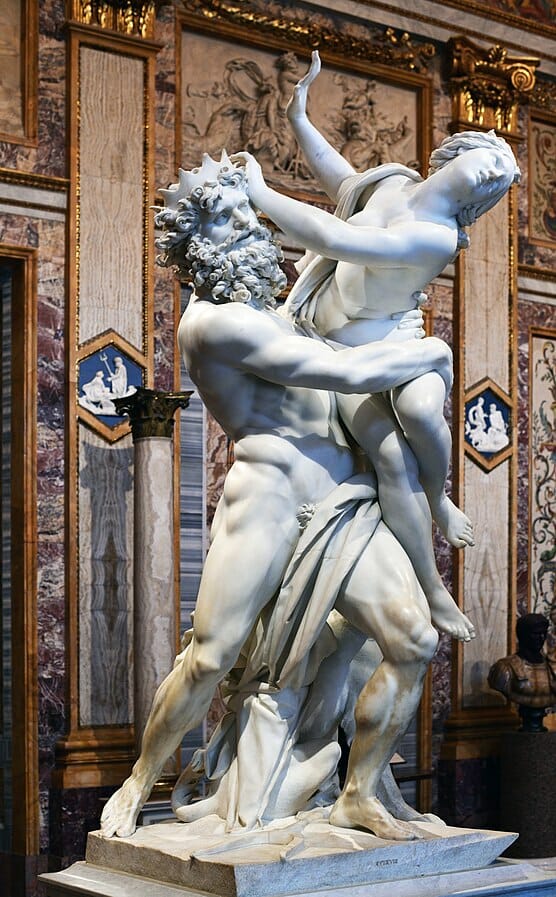

According to the myth, Persephone was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and harvest, and an overprotective mother who kept all men from her daughter. The god of death and the king of the underworld, Hades – brother of Zeus – fell in love with Persephone and abducted her while she was gathering flowers, bursting through a cleft in the earth and dragging her with him into hell. Demeter, desperate to take her back, began a negotiation with Hades full of tricks and frauds. Neither of them wanted to give her up. In the end, Zeus decided that Persephone would spend half a year with her husband in the underworld and the other half with her mother on Olympus. With this myth, the Greeks explained the alternation of seasons.

A deceptive sympathy

When Hades decided he loved this girl

he built for her a duplicate of earth,

everything the same, down to the meadow,

but with a bed added.

In A Myth of Devotion, Glück focuses on Hades’ role in the myth. At first, he appears as a thoughtful lover who wants Persephone’s first time in hell to be as comforting as possible. A gentle introduction to the shadows. However, what seems to be a sympathetic revision of Hades soon reveals its true purpose. The abduction results from years of planning and observation, but somehow Hades fails to consider Persephone’s potential reactions or fears. He does not see Persephone as an individual: she is just a projection of his ideas and feelings. He wants her, and he takes for granted the fact that she will be happy only because of his love.

That’s what he felt, the lord of darkness,

looking at the world he had

constructed for Persephone. It never crossed his mind

that there’d be no more smelling here,

certainly no more eating.Guilt? Terror? The fear of love?

These things he couldn’t imagine;

no lover ever imagines them.

Society’s myth of devotion

Glück writes about a bitter vision of love. In this poem, whether maternal or romantic, love is a means of subjugation, something harmful to the beloved. In the quarrel between Demeter and Hades, Persephone disappears. Within a few lines, Glück shows that when love is blinding, lovers become oppressors. Therefore, the title acquires a double meaning: the poem tells a myth that involves devotion, but at the same time, it shows how devotion is just a myth, a mystification that poisons relationships.

However, Glück does not take a judgemental point of view. As she states in Persephone the Wanderer (I): “The characters/ are not people./ They are aspects of a dilemma or conflict.” Hades’ actions are not under the filter of moral inquisition. On the contrary, in A Myth of Devotion, Glück always seems to imply his good faith. Nonetheless, the several rhetorical questions and the insistent comparisons between what Hades wants and what everyone wants are powerful expressions of Glück’s irony.

Her tone guides the reader towards a more critical analysis, not only of the myth but also of love as we know it in society.

A soft light rising above the level meadow,

behind the bed. He takes her in his arms.

He wants to say I love you, nothing can hurt youbut he thinks

this is a lie, so he says in the end

you’re dead, nothing can hurt you

which seems to him

a more promising beginning, more true.

In 2020, Louise Glück won the Nobel Prize for Literature “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

Tag