Orpheus and Eurydice | The seeds of Titian's style

Artist

Year

Country

The painting of Orpheus and Eurydice belongs to the early activity of Titian Vecellio. Probably painted in about 1512, it was purchased by the collector Guglielmo Lochis and now it is located at the Carrara Academy in Bergamo. In this work, Titian reinterprets the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice by the Metamorphoses (8 AD) of the Roman poet Ovid.

An uncertain attribution

The painting was initially attributed to the Venetian painter Giorgio Barbarelli, also known as Giorgione, but in 1927 the Italian critic Roberto Longhi affirmed it as being by Titian himself. It is not the first case of incorrect attribution between the two Venetian painters. It already happened with Concerto Campestre (1510) and with several unfinished works by Giorgione completed by Titian after his death such as the Venere dormiente (1508).

The confusion among the critics is due to the fact that Titian’s earliest style was very similar to Giorgione’s since they both belonged to Giovanni Bellini’s workshop in Venice where they inherited the intuition for the revolution of the color and the representation of the landscape. Moreover, Giorgione and Titian worked together influencing each other at the Fondaco dei Tedeschi frescoes between 1505 and 1508 but there are very few remaining parts of these works due to deterioration deteriorated by atmospheric agents.

The horizontal narrative

The author depicts two different chronological moments of the myth. In the foreground, a serpentine figure is biting to death Eurydice, who is dressed in a bright white drapery. Titian continues the tradition of the l’Ovide Moralisé, which was a 15th Century French adaptation of Ovid’s verse, in as much it concerns the iconography of the snake with dragon features, representing the lindworm of the Northern European mythology, a bipedal dragon sometimes pictured without wings. The same creature will merge in the legend of St. George fighting against the Dragon portrayed by several artists such as Paolo Uccello and Raffaello Sanzio.

On the right is Orpheus, portrayed returning from Hades with his wife Eurydice, after he has convinced the Gods of the Underworld to return his beloved to him, thanks to his mastery in playing the lyre. He turns back to look at her violating the pact made with Persephone and Hades. As consequence, Eurydice is lost forever and banished to hell, the cone-shaped structure filled with flames behind her back which is accessed through the infernal gate.

A revolutionary landscape and color

The setting and the colors are the protagonists of the painting, a result of the artistic tradition of the Venetian school of the early 16th century. Venetians revolutionized the visual art of that age by introducing the sentiment for nature, and Tonalismo that consisted of gradually spreading the color tone over tone in overlapping glazes, thus obtaining the perfect fusion between figures, backgrounds, and landscapes.

Orpheus and Eurydice is divided into two opposites landscapes that reflect the emotions of the protagonists and stands respectively for the world of the living on one side and of the dead on the other. On the left, white is the dominant color, the viewer can see a peaceful and bright-colored landscape crowned by the bell tower of Piazza San Marco in Venice.

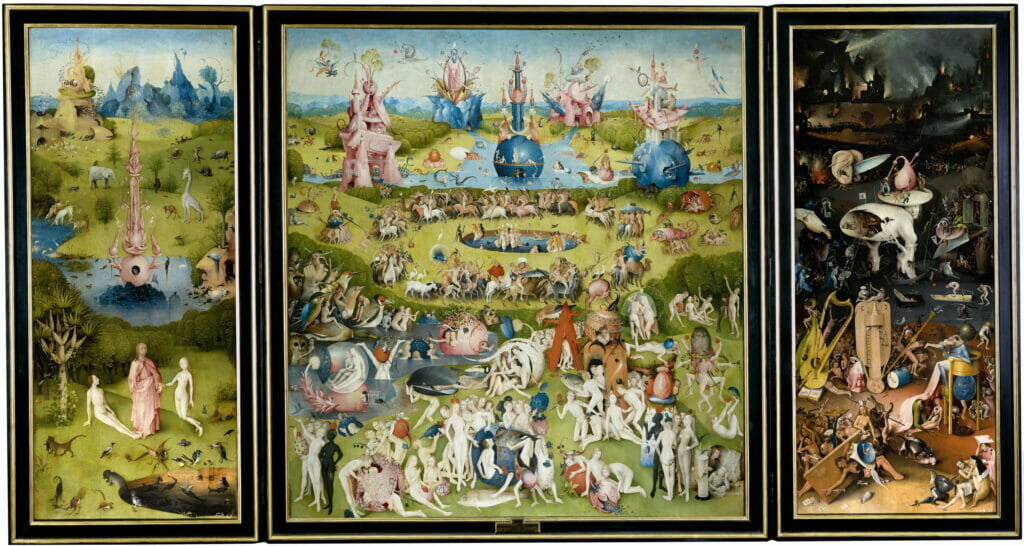

Whereas on the right side, dominated by the color red, Titian portrays Inferno and its gate immersed in a landscape shrouded in smoke and fires, probably having in mind Bosch‘s illustration of the Hell in the right panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), whose similarly tones and nature sharply oppose those of the previous panels of Eden and Creation.

Ultimately it is the color and not the drawing (as like happened in contemporary Tuscan painting that followed Giotto‘s example) defines the shapes and perspective space of the canvas through the effects of light and shadow.

The seeds of Titian’s style

Apart from in than in Orpheus and Eurydice, the illusion of spatial perspective originating from contrasting chromatic masses, a more fluid and theatrical narration, a peculiar disposition of the figures, and the tonal sweetness of landscapes, can be found in Titian’s three frescoes for the Scuola del Santo in Padua. These works, commissioned in 1511, are his first independent commission after Giorgione’s death and his earliest securely documented paintings (Sarah Wilk, Titian’s Paduan Experience and Its Influence on His Style, 1983). Thanks to these similarities critics have established Orpheus and Eurydice‘s date of creation as being in the same years of Padua’s frescoes.

However, Orpheus and Eurydice is assimilated into two other commissions of mythological subjects, based upon Ovid’s Metamorphoses, dating between 1506 and 1508: The Birth of Adonis and The Forest of Polydorum, both located in the Musei Civici in Padua. These last two works could appear to form a cycle with Orpheus and Eurydice, since they share the same literary source, the horizontally developed narrative, and the predominance of the landscape over the figures. As result, this could anticipate the date of the painting from between 1511 to 1506.

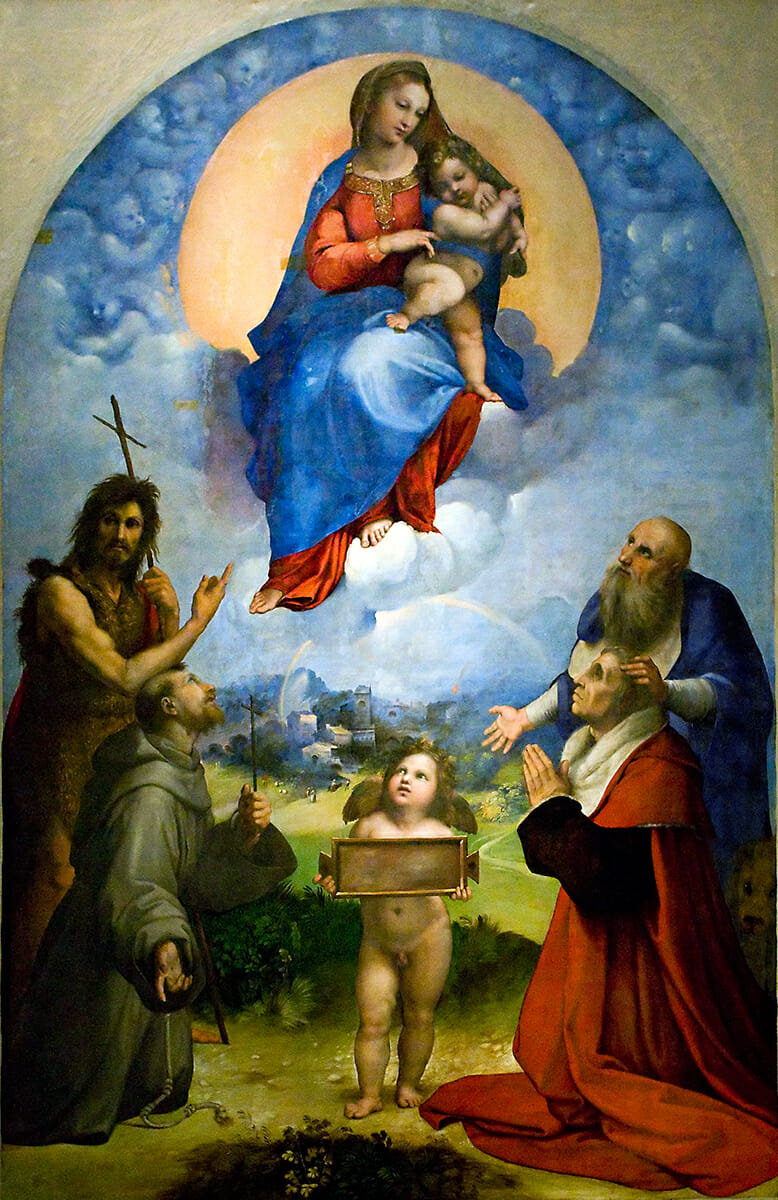

These early works are essential to understanding his artistic training and development as they contain the seeds of an artistic revolution in the use of color and of the figure that would bring Titan his fame, culminating in the revolutionary Assumption of the Virgin (1516-1518) and Pesaro Madonna (1519-1526). As a result of these, critics equate his skill in colors to Michelangelo’s mastery of drawing.

A prolific love myth

The Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice has enjoyed widespread fame since ancient times, becoming prolific in the most varied artistic forms. In art it has been represented by artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, and Eugène Delacroix, in films such as Le sang d’un poète (1930) by Jean Cocteau, in drama by Jean Anouilh’s 1941 Eurydice, in ballet by George Balanchine’s 1948 Orpheus, and in music such as in Euridice by the Italian songwriter Roberto Vecchioni.

When it comes to literature, many authors have reinterpreted Virgil and Ovid’s classic versions of the myth that stood as a symbol of love that overcomes death, twisting the story and the perspectives. In particular, the writers of the Twentieth century wonder why Orpheus turned around and give an active voice to Eurydice’s emotions.

Concerning the first solution, Cesare Pavese in the dialogue titled L’inconsolabile contained in Dialogues with Leucò (1984) focuses on Orpheus’s character. His Orpheus does not care about love anymore because a greater destiny is waiting for him. He does not go to the underworld to get Eurydice back, when after death she becomes “something else”, but to save himself. In fact “it is necessary that each one descend once into his own hell” to forget the past and move on.

A different solution is given by Dino Buzzati in his graphic novel Poem Strip: Including An Explanation of the Afterlife. Published in 1969, Buzzati reinterprets freely the myth transporting it to the hippy climate of Milan in the 60s, charging it with an explicit eroticism considered scandalous for that time. Orfeo becomes Orfi, a rock singer who plays the guitar instead of the lyre. In Buzzati’s version of the myth, Eura (Eurydice) herself does not follow Orfi in the world of the living because death can be defeated only by accepting it.

Instead, a female perspective is given by the Russian poet Marina Ivanovna Cvetaeva who gives a personal reinterpretation of the myth in her Eurydice to Orpheus contained in Posle Rossii (1928). Cvetaeva overturns the situation by exploring Eurydice’s point of view. According to her, Orpheus’s intervention of saving her awakes the memory of a past and irrecoverable life, impeding the serenity brought by death. That is why she tells him “forget and abandon me” instead of the Ovidian version portrayed by Titian in which

she could not say a word of censure of her husband’s fault; what had she to complain of – his great love?

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book X.

Tag