Poetry –

Wislawa Szymborska, Some People Like Poetry

but what is poetry anyway?

More than one rickety answer

has tumbled since that question first was raised.

But I just keep on not knowing, and I cling to that

like a redemptive handrail.

In her poem, Some People Like Poetry, Nobel Prize winner Wisława Szymborska makes an age-old question explicit: what is poetry? To her, the essence of poetry remains unknown. While dwelling on the awareness of how impossible it is to describe something so impalpable, she describes the function of poetry as extremely concrete. To the Polish writer, poetry provides us with a feeling of support and safety, like a handrail does when going down some steps.

Szymborska, in the poem, notices that many writers have attempted to answer the same question. That is true: many poets have tried to explain to others and to themselves the art of writing in lines. Metapoetry is in fact a term born to indicate poems that deal with the topic of poetry. These texts are not theoretical dissertations on the value of poetry. As a matter of fact, they use the same, powerful tools of regular poems: images that convey a message or feeling.

Fernando Pessoa: poetry as a game of mirrors

During his literary career, the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) had many alter egos. He built entire new identities for himself, which included appearance, deeds, and political leanings. He used all these versions of himself to sign many of his literary works. On the contrary, he signed Autopsychography with his real name and surname. The title of this poem involves a substitution: he refers to the term autobiography but replaces “bio” (the ancient Greek root for “life”) with “psycho” (“mind” but also “soul”). Indeed Autopsychography is a voyage inside the conscience to explore the mysteries of poetic creation.

The poet is a man who feigns

And feigns so thoroughly, at last

He manages to feign as pain

The pain he really feels

Poetry is usually associated with truth. El poeta dice la verdad (“The poet speaks the truth”) is the title of a famous poem by Federico Garcìa Lorca, in his Sonnets of Dark Love. Pessoa disagrees with that statement. To Pessoa, to fully express the impulses of the soul, the poet has to use an element of fiction. El poeta è um fingidor, he says, where the noun derives from the Latin word fingere, which stands for “to pretend,” but also “to create,” “to shape.” Even Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi, in his poem The Infinite, uses the word fingere to write about the possibilities of imagination.

Whatever he wants to write, the poet must appeal to the imagination. However, imagination doesn’t necessarily mean deceit. To narrate the pain he experienced, the writer needs to imagine, to build it in his mind. This leads to a paradox: to tell the truth, the poet must feign.

And those who read what once he wrote

Feel clearly, in the pain they read,

Neither of the pains he felt,

Only a pain they cannot sense.

Pessoa goes on to illustrate the game of mirrors activated by poetry. After the writer, it’s the turn of the reader. When he reads about the pain, he comes into contact neither with the real pain of the poet nor with the one he faked. The pain the reader experiences has nothing to do with the tangible reality. He borrows a feeling and dives into it on his personal wave, no matter where it comes from in terms of space and time. As a consequence, poetry is a powerful instrument of empathy: it makes the readers feel others’ sorrows and soothes the loneliness of the human condition.

As a result, poetry is a silent appeal to emotions, offered and received by two souls longing to share. Something similar is explained in a scene of The Postman, a 1994 movie directed by Michael Radford. In this movie, Massimo Troisi plays a man who is a postman on the small island of Procida, where the famous poet Pablo Neruda (Philippe Noiret) lives. Troisi’s character learns to love poetry through his encounters with the latter.

Emily Dickinson: poetry as electricity

In the first of the six books of De Rerum Natura, the Latin poet Lucretius seizes the opportunity for a preliminary declaration of poetics. He compares the pleasantness of poetry to honey on the edge of a glass and the usefulness of truth to bitter medicine. Medicine – the Epicurean philosophy he intended to spread in Rome – is the ultimate goal. Still, honey is the necessary means without which the patient would never drink the bitter cure. Among the ancients, this declaration of intent was familiar, from literature to oratory.

Eight centuries afterward, Emily Dickinson, while working on a less institutional project, does not feel the need for any definition of warning. Nonetheless, her free verse, in the poem To pile like Thunder to its close, holds something close to an explanation of what poetry meant to her. It sounds like a wish for her own words: reaching the intensity of thunder, the word of God.

To pile like Thunder to its close

Then crumble grand away

While Everything created hid

This — would be Poetry —

Or Love — the two coeval come —

We both and neither prove —

Experience either and consume —

For None see God and live —

To Dickinson, poetry is electricity. The thunder erupts when the sky has accumulated such electrical energy that it can no longer postpone the lightning. In the same way, the poem unloads on the sheet the emotional and intellectual charge accumulated during certain intervals of silence. Dickinson’s metaphor seems to suggest that silence is the dark side of poetry. Without it, there would be no accumulation of electricity. That is, there would not be that potent mixture of meaning and personal experience through musicality. So, the poem would not hit its mark, it would be, actually, discharged.

In this poem – number 1,247 from Dickinson’s corpus – thunder, poetry, love, and God are placed on the same level. The first three elements are the manifestation of the last one. Poetry, in its essence, would coincide with God’s word, identified with thunder in more than one passage of the Bible. But the conditional (“This – would be Poetry”) indicates that it is a utopian aspiration. The experience of poetry, as human, is never total and absolute like the ideals that inspire it. It is impossible for humankind to fully get to know them. Anyone who experienced them would be consumed.

Almost at the same time, the French poet Arthur Rimbaud was working out a somewhat similar idea of literature. He too believed that making true poetry would lead to consummation. According to Rimbaud, the artist’s task is to melt into his own creation. But, consistent with the recklessness of the cursed poet he was, he did not want to give it up. On the contrary, he sought poetry precisely for this reason. It turned into it as an extreme adventure. A game in which – Dickinson would say – “all is the price of all.” And in which who consumes wins.

Antonio Machado: poetry as a song

The poem From my briefcase by Antonio Machado, published in 1924, illustrates the elements which Machado considers the pillars of poetry. The choice of the title is significant: if a worker keeps his instruments or documents in a briefcase, the poet keeps the keys of poetry–writing in this particular text, as if it was a folder.

Musicality has always been an essential aspect of poetry: poetry is, in fact, the language context where the sound of words does matter and makes the difference. However, for some poets, music was everything in poetry. One example is the symbolist Paul Verlaine’s famous line: “Music before anything else.” This idea inspired many poets at the end of the nineteenth century like Rubén Darío, the Nicaraguan poet and father of Modernism in the Hispanic world. Antonio Machado, the leading figure of the Generation of ’98, clearly took a distance from this radical view, without denying the importance of music either.

Chant and Tale is Poetry.

One sings an alive story,

telling its melody.

According to Machado, poetry is a fusion of music and the story told. Apart from the first line, where the idea is clear, the other lines express the importance of such a fusion through the association of the verb “sing” to the noun “story” and of the verb “tell” to the noun “melody.”

Therefore, Machado’s poetry “Prefers the poor rhyme / and the indefinite assonance,” which is why he chooses metrical forms that are all characterized by the assonance: soleá, the three-verse Andalusian combination, copla, the poetic form intended to be the lyrics of a song, and romance, which has no strict stanza division and forms narrative poems. But the importance of these metrical forms goes further: they all form part of the popular tradition, so Machado shows how poetry should be simple and belong to everyone, not just to an élite. Moreover, they have an intrinsic connection with music: soleá represents one of the most important palos (“cantos”) of Flamenco; romance was part of the oral tradition and sung by troubadours; copla is present in the folkloric Spanish music.

Not hard and eternal marble,

Neither music nor painting,

but word in time.

According to Machado, poetry is a deep intuition that sprouts when the soul meets the world. In this meeting, time is bigger than us, and yet it is us. The poet doesn’t introduce the concept of time in a philosophical discourse. Instead, he shows that time is something strictly concrete in human life. That is why he prefers “the verbal and poor rhyme, / and temporal“: in fact, the verb is action and action occurs in time.

All the imagery

that didn’t sprout from the river,

cheap imitation jewelry

The flow of time is compared to the flow of the river: the inspiration for such a view comes from Jorge Manrique, the Spanish poet of the fifteenth century who wrote that “Our lives are rivers, gliding free/ To that unfathomed, boundless sea, / The silent grave!” and the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus‘ ever-present change and pantha rei (“everything flows”). According to the poet, capturing the essence of life and its temporal fluidity is the brilliant goal of poets.

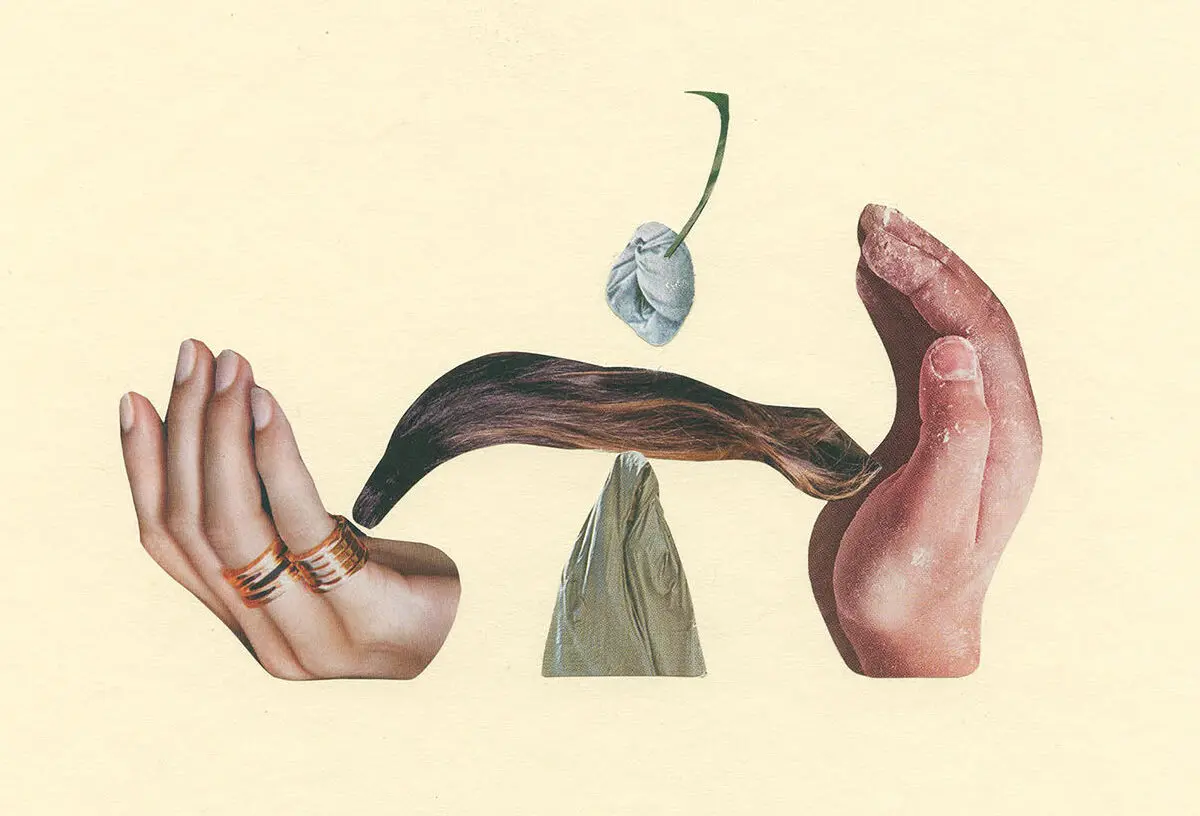

Analogue collage created by Luisa Romussi. Have a look at the project and her profile on Instagram.