Here by Richard McGuire | The Graphic Novel that Redefines Time - Review

Author

Year

Format

By

My dad took the same photo of us every year in the same spot as we grew up, […] All the photos of family stuff all look the same.

Richard McGuire

With these words, Richard McGuire sums up the heart of Here, a comic that explores the passage of time through overlapping moments in the same room. And in which everyone, anywhere in the world, at any time, eventually finds themselves living the same experiences.

American illustrator and author McGuire first published Here in 1989 as a six-page strip in the magazine Raw, edited by Art Spiegelman (Maus). The idea was born when a roommate told him about Windows, the operating system released a few years earlier. Fascinated by the possibility of displaying multiple windows at the same time, McGuire applied this principle to narration, showing the same space in different eras. In 1991, this version was adapted into a short film.

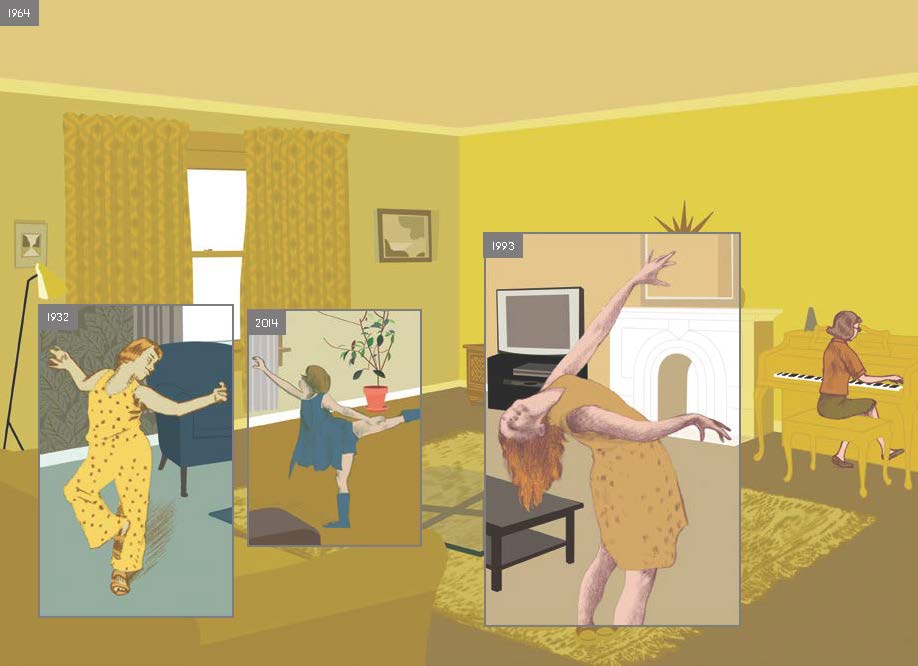

After over twenty years, McGuire resumed and expanded the project. The 2014 graphic novel, published by Pantheon, has a more intimate dimension. The author set it in his childhood home, incorporating family photographs and historical research on New Jersey. The book thus becomes a journey through time, where past and future intertwine in a single image. In Here, space transforms into memory.

I think there’s a big difference between the two versions. I see the first one more as a formal exercise in style, while the second one – since I’m older now, I have much more artistic experience and I hope I’m also wiser – has a much more intense emotional connotation.

Richard McGuire in an interview for Fumettologica

A story without a beginning or ending

It’s 1957. A woman walks into the room. She came in to get something, but she can’t remember what. How many times has this happened to anyone? That’s how Here begins.

The entirety of Here takes place in the same physical spot – a corner of a room – but each page overlaps different eras, from the distant past to the most distant future.

Each double page is a window into history, with events that fit together non-linearly. The reader moves between 3 billion BC, with primordial landscapes; 1609, with Native Americans, and 1775, with Benjamin Franklin. The 20th century is crossed by scenes of everyday life, while the future extends to 22,175, showing unknown life forms and once again a wild nature.

Time passes without following chronological logic: a man laughs in 1989, coughs, and collapses to the floor, but his family’s reaction comes only dozens of pages later. In 1949, a mirror breaks, while in 2111, the room floods. The story of the room (and therefore of the entire house) emerges through small details: the wallpaper that changes, the fireplace that disappears, and the television that becomes obsolete.

It almost seems that McGuire wants the readers to experience how Dr. Manhattan perceives time in Alan Moore’s graphic novel Watchmen: not as a linear sequence but as a simultaneity of overlapping events. Each moment coexists with the others, the past, present, and future merge, and the reader becomes an omniscient observer of a story that has no fixed protagonists. In Here, the characters change, it is the place – that corner of that room – that remains.

Past, present, and future: everything exists at the same time

For us believing physicists, the separation between past, present and future has only the meaning of an illusion, albeit a tenacious one.

Albert Einstein

At first, the reader might think that the room is Here’s protagonist, but this is not true. The real protagonist is time. It does not flow linearly, nor does it advance according to logic. McGuire describes a world in which every moment is a connection to others, revealing that time is not a flow but a set of stratifications that influence each other. As William Faulkner says in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is not dead! Actually, it’s not even past.” And this is the principle on which Here is based: every moment exists simultaneously with the others.

A man, in 1986, wears a T-shirt that says Future Transitional Fossil to remind that every life, however unique, is just a link in an endless evolution. The cyclical nature of existence is evident in small gestures repeated over time: birthday parties, manual labor, music, love and death.

This cyclical nature does not only concern individual lives but the entire history of humanity. The philosopher George Santayan famously said “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”, and theory after theory has been elaborated on History repeating itself, on social and political cycles, showing how periods of stability and crisis alternate regularly. McGuire, with his visual story, confirms this vision. Even if with a slight variation.

Our era does not escape this pattern either. Wars, revolutions, economic crises, and rebirths seem to retrace the steps of those who lived in the past. But with each cycle, new variations emerge, new details that change the context without altering the underlying mechanism.

In Here, in 1775, Benjamin Franklyn says “Life has a flair for rhyming events”. McGuire then suggests that History never repeats itself exactly the same, even if in a very similar way, but continues to rhyme with itself in an eternal return that connects past, present, and future.

The aesthetic language of Here

In his graphic novel Here, McGuire combines artistic techniques and influences that give the book an evocative visual look. Hand drawings meet digital coloring, alternating Photoshop, watercolors, and vector graphics to create a layered effect. The author explains that he used such different techniques because he did not want “it to be all ‘hard edge’ vector art.” “I wanted a warmer look. I was playing around with watercolor and gouache and pencil, making rough drawings,” he explains, highlighting the importance of experimentation in his creative process.

The shades vary according to the era, inspired by the color rendering of old photographs. They almost recall Wes Anderson‘s palettes. The colors of the 1950s, with their gray, red, and green colors, contrast with the golden tones of the 1970s photos, creating a palette that guides the reader through the eras. The fixed setting of the room recalls Edward Hopper’s paintings, with empty spaces that suggest a suspension of time. McGuire’s attention to architectural detail, evident in his use of vector graphics for the furnishings, lends the book a tangible realism. In contrast, aligning the room’s perspective axis with the book’s central fold is a visual device to aid reader immersion.

Memory survives

Here has been welcomed with great enthusiasm since its first appearance in 1989. Chris Ware, one of the most influential authors of the modern graphic novel, author of Jimmy Corrigan and Building Stories, said to The Guardian that the discovery of McGuire’s work radically changed his way of thinking:

It was the first time I had had my mind blown. Sitting on that couch, I felt time extend infinitely backwards and forwards, with a sense of all the biggest of small moments in between. And it wasn’t just my mind: Here blew apart the confines of graphic narrative and expanded its universe in one incendiary flash, introducing a new dimension to visual narrative that radically departed from the traditional up-down and left-right reading of comic strips. And the structure was organic, nodding not only to the medium’s past but also hinting at its future.

Chris Ware

Here has also been adapted into a digital version. The e-book emphasizes the central concept of the work: the overlapping of past, present, and future. The reader can, in fact, even change the chronological order of the scenes, offering an even more immersive and engaging experience, which amplifies the idea of a stratified time.

The concept of history’s cyclic nature is part of the graphic novel’s structure. In the first pages, a woman in 1957 enters the room without remembering why she did it or what she is looking for. She is the person with whom Here ends on the last page when she finally remembers what she needs: a hardcover book. Perhaps, then, only memory, recollection, that survives time: those glimpses of a bygone era.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic