The ancient rituals related to the idea of the afterlife constitute a fascinating yet mysterious field to explore. Antiquity offers the opportunity to reflect on different views of death, or on what the afterlife can offer. Depicted or sculpted doors in antiquity had the purpose of faking a larger space in houses but into tombs. The souls of dead Egyptians would pass through and take a boat. Etruscans and local populations of central Italy would banquet or wait for their guardians to open them. However, dying was not the same affair for everyone.

“Opening the secret double doors”

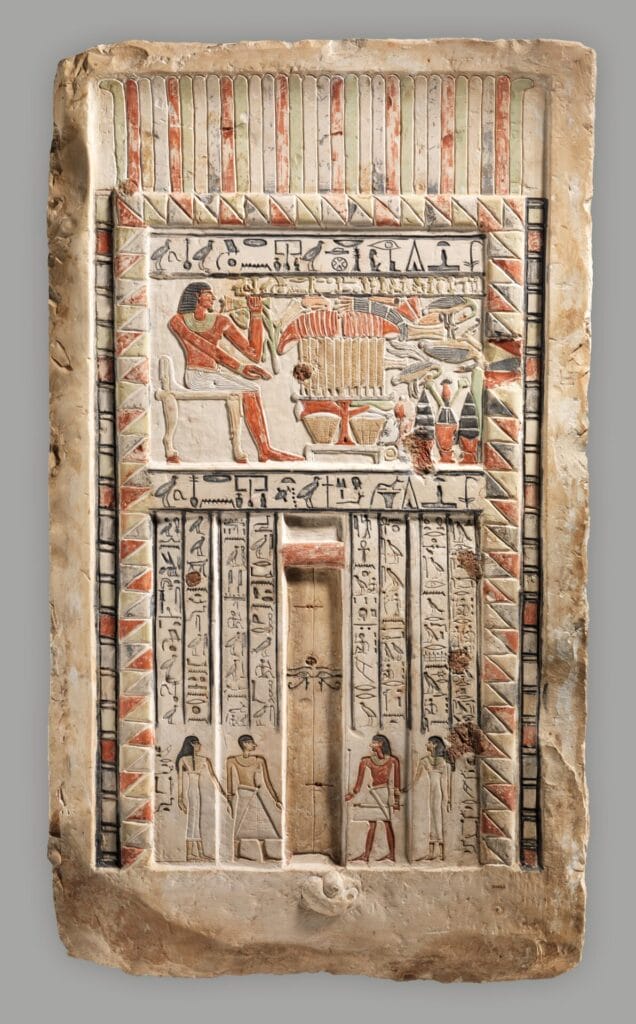

Some of the earliest false doors in tombs date back to ancient Egypt. Once the soul passed through them, Ra himself would introduce the dead person to “the heavenly conclaves” (E. Brovarski, The Doors of Heaven, 1977, p. 110) by floating it on his boat. When Osiris appeared as the god of death, he only would open or close the doors. His judgment (Psychostasia or weighing of the soul) influenced the boat trip. The false doors were monumental and enriched with reliefs with spells and wishes for the soul. Each element had a specific role in the opening or closing. For instance, the leaves were the main barrier between the two worlds. The name of the deceased was repeated so the soul would not be exiled (as in the false door of Wd´-Dri, Cairo Museum). Moreover, these thresholds were not only exclusive for kings or pharaohs but also for other important people (pictures 1-2). The tomb of Mereruka, a powerful officer, preserves a statue of the dead passing through the false door.

Etruscan demons: defending the afterlife with swords and wings

For the Etruscans (9th century B.C., central Italy) rituals were essential, especially the cult of death. Since the 7th century B.C., they built a necropolis (towns of the dead). Burials looked like houses for the afterlife, plenty of lavish frescoes with pleasant and colorful life scenes. Depicted doors connected to the afterlife, guarded by demons. They had wings, their skin was livid blue, and their characters monstrous. They brought swords or axes and took (courteously or not) the dead to the afterlife. The feminine demons were Vanth (François Tomb, half of 4th century B.C., Necropolis of Vulci) and Scilla (Tomb of The Winged Demons, 2nd half of the 3rd century B.C., Necropolis of Sovana), the male Charun (Tomb of Charun, 250-275 B.C., Necropolis of Monterozzi, Tarquinia). As death constituted a sad a traumatic event, Etruscans relied on demons and depicted colorful decorations to exorcise this emotional bearing.

The cult of the dead in the woods: ancient Central Italy and doors made of stone

Into the woods of the Amplero Valley – Abruzzo region (Italy) – Cantone necropolis (1st-century B.C.-1st century A.C.) is a sudden ghastly yet sacred vision. About 50 tombs are the silent witnesses of the life of the Marsi, a community of Italic-Roman warriors who lived here since the 4th century B.C. (959 m.a.s.l.). There are different kinds of burials: fossa, chamber, and gravestones. Two steles imitate a door design borrowed by Romans: the door leaves have four areas, two bring half sphere ornaments, overcome by a stylised fronton. Nevertheless, in this necropolis rituals involved pouring libations into canals to the chamber tombs. Rich goods accompanied the noteworthy members of the community to the afterlife (i.e. ivory beds). These false doors prove that here death was acknowledged as a transition, influenced by Romans and Etruscan. Convivial rituals intensified the passage, wishing an enjoyable afterlife to the dead.

Our afterlife doors

The door as a symbol of transition from the corporal state to a different state – or from the realm of life to a different dimension where to stay – is one of the most ancient and used features. The use of the fake, depicted, sculpted door in antiquity can be easily found also in our times. It only takes a walk into a cemetery. Gates of monumental tombs, like in the Staglieno Cemetery (Genoa) or in the Verano Cemetery (Rome) are only a few examples of this heritage. Death is still seen as a passage to nowhere and our graveyards constitute the legacy of ancient necropolis: the only difference is that sometimes the modern chapels consent to cross the threshold and there are no guardians to keep us inside.