How could a 20th century art movement influence the most-watched Japanese anime in the world? One Piece is a work of art to the most discerning eye, and to fully appreciate it, one must understand the principles of Cubism.

- When It All Began: Painting Made of Cubes

- A revolution or a natural evolution?

- The Many Faces of the Cube

- The affirmation of a phenomenon, the first cubist work

- Analytical Cubism and Synthetic Cubism

- The avant-gardists: Picasso’s leading colleagues

- Orphic Cubism: Harmony in Colours and Forms

- Cubism and Futurism, the spirit of the 20th-century avant-garde

- Carlo Carrà, the intellectual between the two movements

- Artistic Interconnections

- Cubism in the Universe of Eiichiro Oda

- Devil’s fruits, the power of Art

- One Piece from 1997 to the present, beyond time and space

When It All Began: Painting Made of Cubes

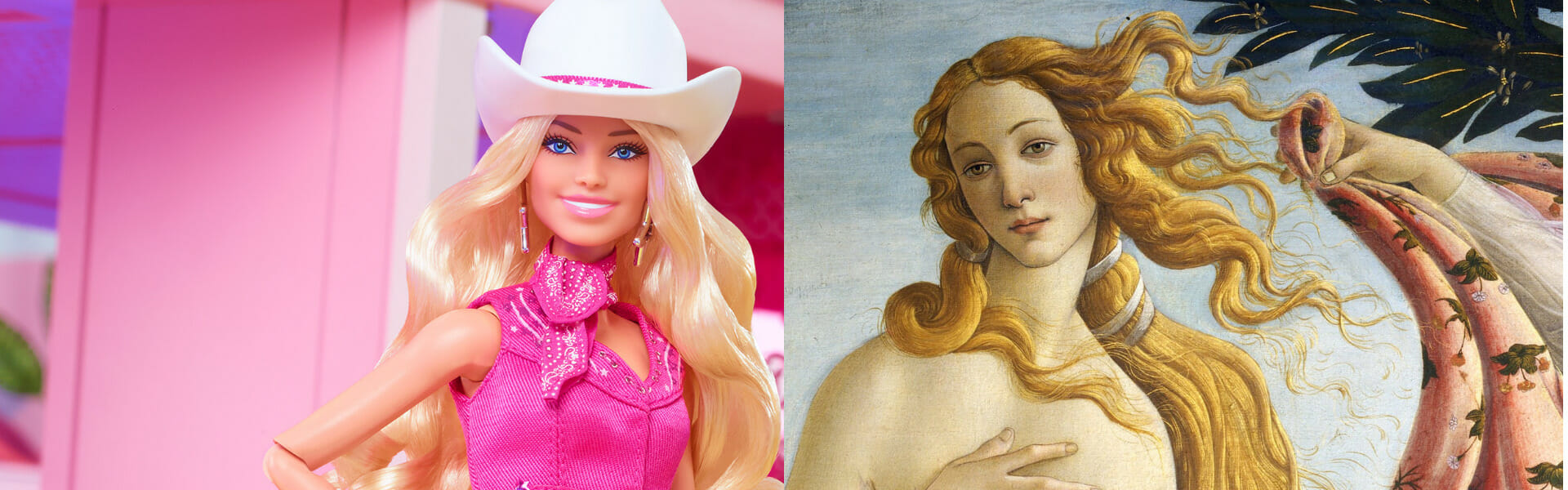

Cubism, an innovative avant-garde movement that emerged in the early 20th century, heralded a seismic shift in the landscape of artistic expression. Founded by visionaries such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Cubism sought to dismantle the traditional approach to representing the world. Art critic Louis Vauxcelles was the first to speak of ‘painting made of cubes’. On the occasion of an exhibition on Paul Cézanne, he said that ‘Braque mistreats forms, reduces everything – places, figures, houses – to geometric patterns, to cubes‘. A description that did not displease the new school of artists who have since called themselves Cubists. Rejecting single-point perspective, the artists fragmented and deconstructed landscapes and figures into geometric shapes and facets. The result is a multi-dimensional representation, presenting a subject from several points of view at once.

Cubism was not only an aesthetic innovation, but also represented a philosophical and intellectual breakthrough. Cubist artists aimed to convey the subjective experience of the viewer. This avant-garde movement reflected the dynamism of an era characterized by rapid technological, social, and cultural change.

Cubism’s impact reverberated far beyond the boundaries of painting. It influenced sculpture, literature and even architecture, leaving an indelible mark on the trajectory of modern art. As an avant-garde force, Cubism challenged artists and audiences to question preconceived notions, inviting them to explore the boundaries of perception and representation in ways never seen before.

A revolution or a natural evolution?

Cubism was inspired by several influential art movements that paved the way for its birth. First and foremost, Post–Impressionism, in particular the works of Cézanne, who explored the geometric structure of objects and landscapes. In addition, the tribal and Iberian art encountered by Picasso played a key role, introducing a fascination for non-Western forms and aesthetics. The fractured perspectives and multiple points of view inherent in Cubism can be traced back to the influence of Fauvism and its bold use of color. These diverse influences came together to break artistic conventions, resulting in the abstract and multifaceted language of Cubism.

Pablo Picasso deeply admired Cézanne, considering him a mentor. The two artists shared a deep friendship in early 20th century Paris. Picasso attributes Cézanne’s revolutionary approach, his forms and structures, as a crucial influence on the development of Cubism, that is why he defined Cézanne “father of us all”.

Image Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago

The Many Faces of the Cube

The affirmation of a phenomenon, the first cubist work

An avant-garde artistic movement cannot be considered as such if it does not evolve. It is in continuous evolution that one manages to break the mold and cross new boundaries.

The first work that opened the Cubist movement was Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), a work by Picasso (then 26 years old) that scandalized the international art scene. An ambiguous depiction of young prostitutes that the author frequented in a Barcelona neighborhood. What disarms the observer are the angular and geometric shapes that look sharp. The exotic-looking maidens demonstrate the impossibility of rendering the three-dimensionality of a face realistic on a two-dimensional surface such as canvas. The aim is to synthesize the subject in its entirety.

Analytical Cubism and Synthetic Cubism

Georges Braque, a French painter, and Pablo Picasso shared an extraordinary friendship. Their bond fostered a creative synergy that catalyzed the Cubist movement. Collaborating from 1908 to 1914, they exchanged ideas, techniques and inspiration, pushing artistic boundaries. In their hands, Cubism was born as analytical, a definition given by the desire to break down and observe the subject from several points, to analyze it and understand it better.

In the last two years of their collaboration, Picasso and Braque reworked their points of view through synthetic cubism, given by the superimposition of parts of the same object, rendered through the techniques of collage and papier collé (glued paper). These techniques are used to best convey the perception of the subject, the artists superimposing different materials, and as the name suggests, even sheets of paper. The viewer can also perceive what he sees through the materials of which the subject is composed.

So as the names of the movement suggest, there is a first phase that aims to analyse the subject by proposing several points of view of it. The second phase goes beyond the first by aiming at the synthesis of the subject through the representation of its totality.

The avant-gardists: Picasso’s leading colleagues

Braque’s distinctive approach was to fragment and assemble objects into geometric shapes, presenting them simultaneously from multiple perspectives. His analytical style is characterized by muted colors and intricate compositions. Many of his compositions, or decompositions, focus on musical instruments such as guitars and violins.

Juan Gris, a Spanish painter, following in the footsteps of his colleagues, demonstrated his mastery in many of his paintings, mastering synthetic cubism in particular. One example is Violin and Glass, executed in 1915. This composition features a violin (with a glass and other elements), a recurring motif in Cubist works, rendered with meticulous precision. Gris’ often muted color palette adds a sophisticated depth to the work. The arrangement of shapes and lines suggests a careful exploration of spatial relationships, reflecting the influence of his contemporaries. The work Violin and Glass encapsulates Gris’s commitment to the principles of Cubism. This shows his ability to fuse intellectual rigor with artistic finesse, making it one of the quintessential representations of the artist’s contribution to the avant-garde movement.

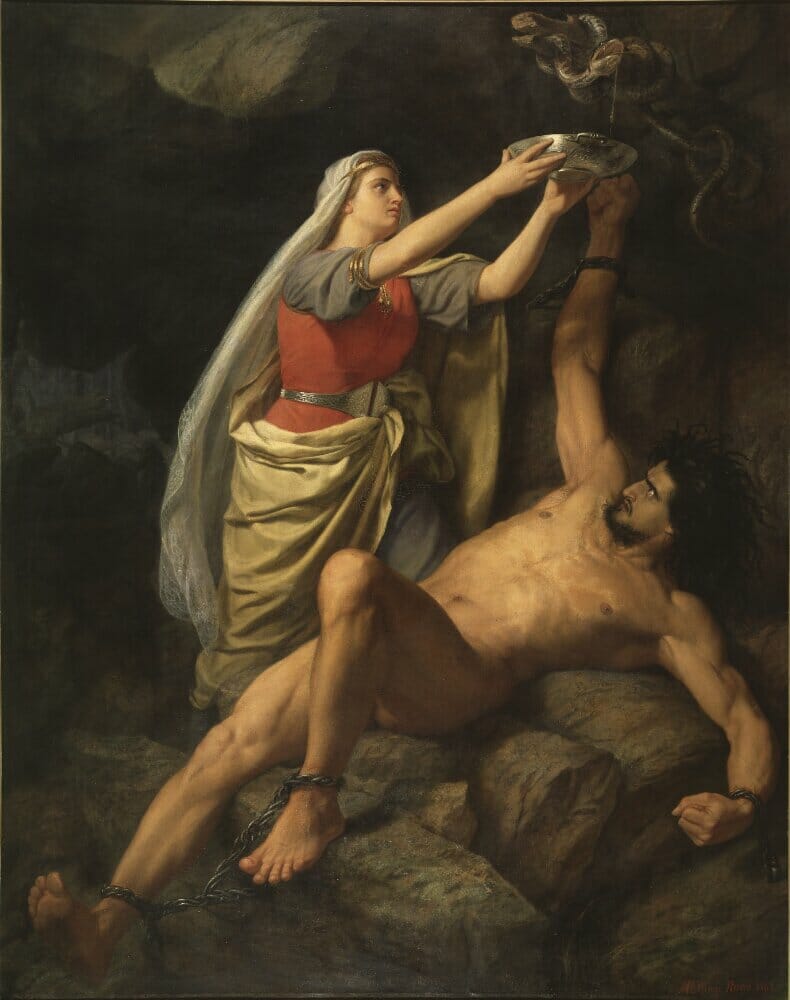

Orphic Cubism: Harmony in Colours and Forms

In the second decade of the 20th century, a parallel style to Picasso’s Cubism developed, leading to pure abstraction. Orphic Cubism was first defined as such in 1912 by the French visionary Guillaume Apollinaire. A symbolist poet but also an art critic and playwright, he always supported and praised the revolutionary inventiveness of the avant-gardes of the time. Orphic Cubism derives from the myth of Orpheus, a singer who uses music as a weapon to bewitch his enemies. Thus Orphic painting aims at a harmony that captivates the observer through contrasting colours and concentric shapes. The Frenchman Robert Delaunay is the spokesman of this Cubist branch. Delaunay’s painting incorporates Orphic philosophy masterfully, as can be seen in La ville de Paris.

In the canvas vivid with contrasts, the subject, a city scene, is dynamic and for this reason closer to Futurism, far from the static nature of the still lifes and portraits of more classical cubism.

Cubism and Futurism, the spirit of the 20th-century avant-garde

Cubism and Futurism were the two main avant-gardes of the early 20th century. They shared a departure from traditional artistic norms, but diverged in their conceptual foundations. Both rejected representational conventions, opting for innovative ways of depicting the dynamism of modern life. Cubism fragmented and assembled forms, presenting multiple perspectives simultaneously. It emphasized subjective experience and the intellectual exploration of structure.

Futurism, led by Filippo Marinetti, celebrated the technology, speed, and energy of the machine age, portraying movement through dynamic lines. Although both movements embraced abstraction, Cubism leaned towards introspection and analysis of form, while Futurism exuberantly embraced the forward-looking spirit of modernity.

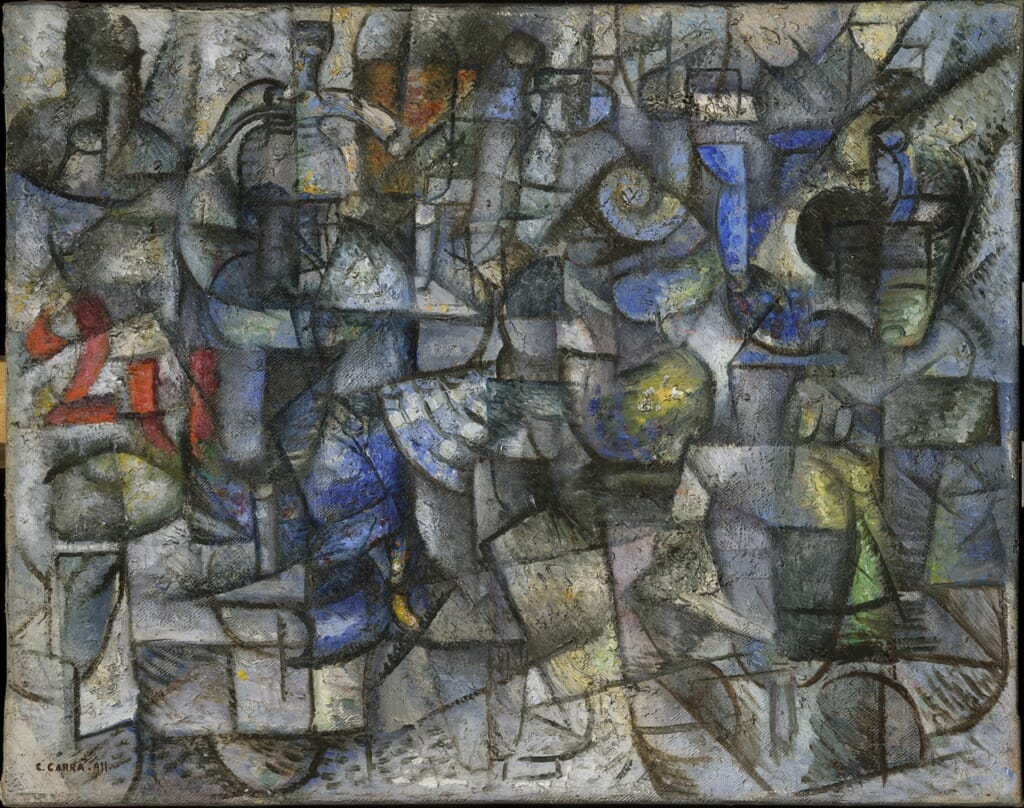

Carlo Carrà, the intellectual between the two movements

Carlo Carrà was an Italian painter and a key figure in the Futurist movement. He played a fundamental role in shaping the aesthetic and philosophical aspects of the group. Carrà’s contribution to Futurism goes beyond his artistic output. His theoretical writings and manifestos influenced the movement’s trajectory, solidifying his legacy as a painter and intellectual force. In his painting Ritmi di oggetti (Rhythms of Objects), created in 1911, one can see the meeting points between the two movements, despite the fact that the author could not call himself a Cubist. In this work, Carrà employs fractured forms and dynamic lines to convey a sense of movement and energy. The objects seem to pulsate with life, embracing the Futurist fascination with the speed and rhythm of the modern world.

Image courtesy of Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano

Artistic Interconnections

Cubism in the Universe of Eiichiro Oda

Cubism may seem far removed from the vibrant and dynamic realm of anime (for this reason perhaps closer to futurism), but its influence has made its way subtly into unexpected corners. In One Piece, the echoes of cubism are discernible in character design and visual storytelling.

The creator of the series, Eiichiro Oda, has imbued his work with endless cultural references. Many of his characters are inspired by existing historical figures such as pirates and Japanese mythology and folklore. One Piece narrates the adventures of Monkey D. Luffy, a spirited young pirate who dreams of becoming the Pirate King. With his motley crew, the Straw Hat Pirates, Luffy explores the vast and dangerous Grand Line in search of One Piece‘s legendary treasure, facing powerful enemies and forging unbreakable bonds.

The characters’ faces are often characterized by geometric simplicity, resulting in angular shapes and sharp lines reminiscent of cubist techniques. The diverse and imaginative landscapes of One Piece sometimes employ fractured perspective, presenting scenes from multiple viewpoints at the same time, much like the fractured spaces found in cubist paintings. Some locations in the series are inspired by Italian cities such as Florence and Venice. Oda has flooded his universe with real-life references, even taking in the architecture of Jerusalem and Park Güell, the park created by Gaudí in Barcelona, to which the cubist par excellence, Picasso, was very attached. Furthermore, the expressive use of exaggerated proportions in the characters, a hallmark of Cubism, contributes to the visual dynamism and unique aesthetic of the series.

Devil’s fruits, the power of Art

Series fans will know that characters gain powers through devil fruits. Each fruit has a specific function and some have a not too veiled reference to Cubism.

Giolla, a member of the Donquixote fleet (and here the reference to Miguel de Cervantes‘ work is undeniable), has eaten the fruit Ato Ato no Mi (Fruit of Art). The latter gives her the ability to transform anything she touches into a work of art that she can mold to her liking. In addition to Cubist references, she revisits other famous works such as Edvard Munch‘s The Scream and Salvador Dali‘s The Persistence of Memory.

Trafalgar D. Water Law, a tribute to Napoleon, is an emblematic character in the series who can be defined as neither good nor bad, but is determined by a strong sense of justice. He joins the crew of Straw Hat (Luffy) to defeat the Donquixote. His power given by the Ope Ope no Mi (Op-Op Fruit) gives him the ability to create a space in which he can manipulate and reassemble anything, including people. In short, a power worthy of Picasso.

One Piece from 1997 to the present, beyond time and space

One Piece began as a manga in 1997, and two years later it was broadcast for the first time. After more than twenty years, it is still the best-selling manga with over 400 million copies sold. Still today, One Piece therefore still has a loyal, multi-generational audience. On 31 August 2023, Netflix launched the live-action series inspired by the anime, which has won over nostalgics and new followers alike. Although One Piece does not declare its debt to Cubism, the subtle incorporation of its principles adds a level of complexity and visual intrigue to the anime.

This shows how artistic movements can transcend their original contexts and find resonance in unexpected creative realms. The boundary between two such distant worlds becomes a fine line if we look at the contribution they made to their respective fields. The Cubists revolutionized modern art, or rather the vision of it. Eiichiro Oda revolutionized the world of manga and animation by creating an intricate, but well-made and therefore enduring product. It is not an isolated case that painting mixes with animation. Just think of the latest exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum, where Pokémon became impressionist paintings. Art in all its inclinations is an eternal testament to revolutions and evolutions. The interweaving of different forms can only give rise to beauty.