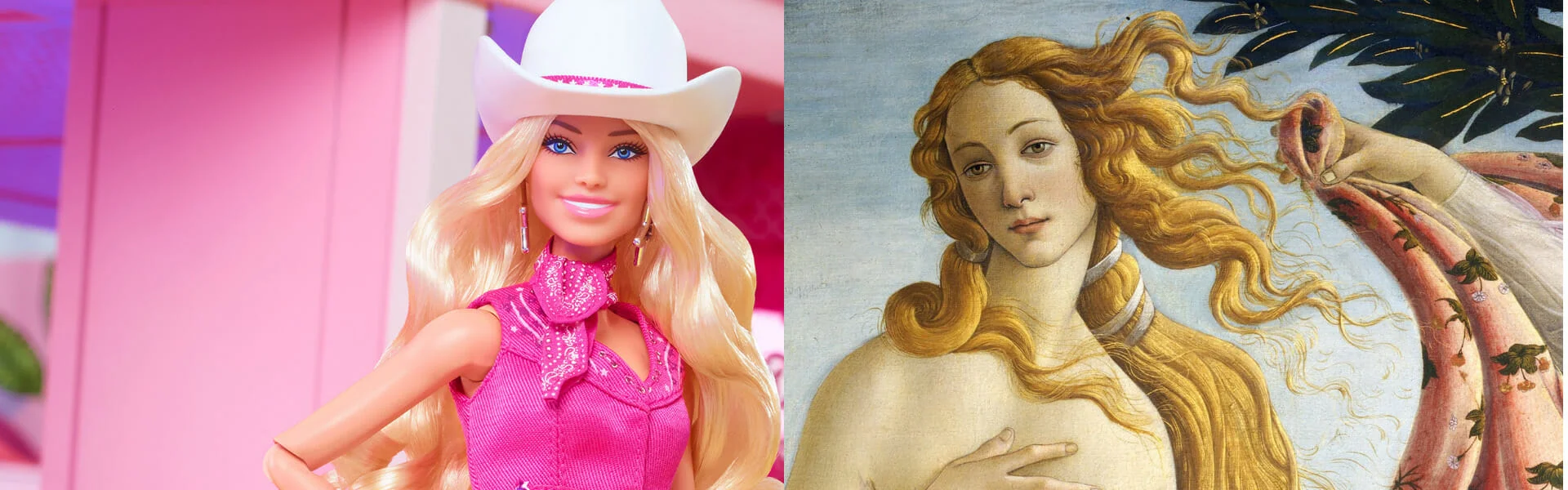

The Birth of Venus and the iconic Barbie doll are two very different cultural objects. The former is a famous Renaissance painting created by Sandro Botticelli in the 15th century, depicting the goddess Venus, while Barbie is a popular line of dolls launched in 1959 by the Mattel production company. However, what Botticelli’s Venus and Barbie have in common is the concept of idealised beauty. Both subjects become icons of beauty in their respective historical and cultural contexts. Indeed, Botticelli’s Venus is often celebrated for her grace and aesthetic perfection, while Barbie was modelled with idealised physical features and body proportions that were considered perfect even if unrealistic. Both figures invite us to reflect on how ideas of beauty and the concept of femininity have evolved over the centuries, moving from classical aesthetics to modern pop culture influences.

Sandro Botticelli, one of the masters of the Italian Renaissance

Sandro Botticelli, whose real name was Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, was a famous 15th-century Italian painter, born in 1445 in Florence. He has been one of the great masters of the Italian Renaissance. The artist worked for various prominent figures of the time, including members of the Medici family. In spite of his talent and popularity, Botticelli fell into disgrace during his last years of life, when he was seized by a strong conversion and came very close to Savonarola‘s theories: his artistic production was affected by this new view of the world, which was at times mystical and visionary. However, over time, his entire production has been re-evaluated and appreciated as a milestone of Renaissance art.

His influence is still evident in art history and his works are recognised and admired worldwide. Botticelli is famous for his depictions of mythological, religious and allegorical subjects. His paintings are characterised by the use of bright colours and elegant, graceful figures.

Visualizza questo post su Instagram

His most popular work is the Birth of Venus, a painting depicting the goddess Venus emerging from the foam of the sea, foam caused by Uranus’ member falling into the water when he was emasculated by his son Saturn. The work may have been commissioned by the Medici family, one of the most influential families of the Italian Renaissance. Today, the painting location is in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence together with another famous work by the artist, The Spring.

The Birth of Venus, the creation of an icon

The Birth of Venus is a painting made by Botticelli around 1485-1486. This work depicts Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, landing on the island of Cyprus. The painting shows Venus, intent on covering her nudity with her long blond hair, surrounded by mythological figures. Her pose is delicate, as she is pushed on a shell towards the seashore by the Zephyrus wind. He embraces a female figure, perhaps identifiable with another wind such as the Bora. On the right instead, there is a nymph, representing the Hour of Spring, waiting to dress Venus in a mantle of flowers.

The composition, the delicate tones and the elegant movement of the figures give the painting a harmonious and dreamy atmosphere. The Birth of Venus is an iconic work of the Italian Renaissance and one of Botticelli’s most famous masterpieces. For this aesthetically refined canvas, which recalls classical mythology, the artist depicts Venus with body proportions that reflect the ideal aesthetics of the Renaissance. The figure of Venus is slender and sinuous, following the aesthetic ideals of the time. However, the painting has some exceptions to the actual anatomical proportions. Venus’ neck is elongated and slender, while her arms appear slightly lengthened.

The divine beauty of Venus, the proportions of a goddess’s body

Botticelli transposed the aesthetic canons of 15th-century beauty onto canvas. They dealt with high foreheads, pale skin and a body with pronounced forms and abundant hips. Botticelli’s Venus and the other female figures in his works such as The Spring (1482) and Portrait of a Young Woman (1480-14805) all embody the ideal of beauty that women sought to emulate. In creating his Venus, the painter took inspiration from the classical models of the ancient Greek statuary of Venus pudica and Anadiomene, whose poses and balanced forms he took up.

The first treatise on the proportions of the human anatomy, the Canon of Polyclitus, dates back to the classical period of Greek art. In 450 B.C., the Greek theorist Polyclitus began measuring various bodies of young people in order to search for the proportions of the human body. His goal was to create a human sculptural figure that was as close to reality as possible. He discovered that once the measurement of a finger or a head was established, all the remaining proportions of a figure could be calculated. From then on, the Canon became a reference model of ideal beauty in representations of human figures.

Barbie, the unrealistic proportions of a perfect body

In 1959, Mattel introduced Barbie to the international market. The lesson of Polyclitus is forgotten and, consequently, the harmonic relationships between the various parts of the body. The model of harmonious beauty of the classical Venus is surpassed and taken to exasperation by the modern Venus. Barbie, indeed, possesses unrealistic measurements with her neck, arms and waist disproportionate to the rest of her body parts. According to Focus, if Barbie really existed, she could not lift her head because of her too-thin neck. She could not even lift weights because of her very small wrists. Furthermore, her legs are twice as long as her arms and her small feet would force her to crawl instead of walk.

In 1992, the best-selling Barbie doll ever, Totally Hair Barbie, was released. The canon of beauty became an unattainable, almost virtual model, and for this reason, perhaps, so desired. Kilometre-long legs and tiny circumferences are what the society of those years demanded. Over time, Barbie adapted to changing generational tastes, and the following came to life: Barbie Petit, Barbie Tall and Barbie Curvy. The doll will therefore adopt more realistic sizes and hair with various hairstyles and colours than the canonical blonde hair. Another important innovation came when, in the 1980s, the first black Barbie was born, under the banner of a more inclusive canon of beauty.

Anatomical Venuses of the 18th century: macabre Barbies?

Intriguing, albeit macabre, life-sized antique ‘dolls’ were the anatomical wax Venuses of the 18th century. Medicine was in full development and the study of female anatomy through such models became widespread as the bodies could be opened and explored at will. These ‘sleeping beauties’ (M. Sardina, Amedit 34, March 2018, pp. 26-29) were born in the second half of the century in France and England, created, among the first, by Guillaume Desnoues (1650-1735) and Abraham Chovet (1704-1790). In Italy, the ‘enlightened pope’ Benedict XIV (1675-1758) favoured the appearance of such sculptures, which were both gloomy and sensual. The waxworker Clemente Susini (1754-1814) distinguished himself by modelling the most important ones.

Venus-zombies: ambiguous beauty between Eros and Thanatos

Making these Venuses calls into question different types of knowledge and techniques, first and foremost ceroplasty. The lying young Venuses were naked, surrendering, similar to their Renaissance predecessors, apparently caught in the act of falling asleep. The removable parts open up revealing in layers the internal organs, right down to the womb, which often contained a foetus. Gestures and features inherit the sensuality of Giorgione’s Venuses (1510) and Titian’s (1538). The sinuosity recalls Botticelli’s antecedents such as the Birth of Venus (1485) or the Hellenism of the Venus de’ Medici (1st century BC)

The head of the anatomical Venus is reclined backwards, followed by the neck that draws an emphatic ‘S’ curve. On the face the eyes are half-open and the lips are barely parted. All the details contribute to an ambiguous image, oscillating between eros and death. One perceives an idea of passive beauty, which makes such sculptures more of ‘zombie dolls’ (M. Sardina, Amedit 34, March 2018, pp. 26-29) than smiling Barbies.

Anatomical Ceroplastics: Medical Instruments from Votive Origins

The function of these perturbing Venuses was to study female anatomy. Anatomical parts had to be reproduced with precision. The ceroplasters therefore were highly skilled in their art, as well as careful connoisseurs of anatomy. The statues consisted of a metal core that supported all the other wax components. The eyes were made of glass, the hair was real. Susini’s Venus de’ Medici had a necklace made of real pearls that strategically covered the line of the neck, where the chest opened up. In history, anatomical waxwork has its roots in the ancient practice of ex-voto production. Since the classical era, anatomical ex-votos were in fact widespread, made of terracotta as well as wax and metal.

Barbie, the transformation of an icon through the generations

Put on the market on 9 March 1959 by Mattel, Barbie imposed herself in global iconography right from the start. She was born with a distinct identity, to the point of having a full name: Barbara Millicent Roberts. She went from being a toy to being a standard of beauty, of style. As a symbol that spans generations, the doll itself has evolved with the changing society. Over the years, Barbie dolls have been created to represent the most varied careers, even those furthest from the female canons, with different ethnicities, and above all different physical forms and abilities, in the name of inclusiveness, an essential value of today’s society.

A constant that has always accompanied the figure of Barbie is Ken. He too underwent several transformations but always remained faithful to the figure of a character at Barbie’s service. It’s an avant-garde and feminist condition considering the times in which it was created (1961).

Margot Robbie, an imperfect Barbie in a perfect pink world

Barbie becomes flesh and blood for the first time with Greta Gerwig‘s live-action. The director, a multiple Oscar nominee, chooses Margot Robbie as the lead actress to bring the iconic doll to life. In Barbie’s world, everything is pink and perfect, fake, except for the protagonist, who is considered less than perfect and therefore forced to embark on a journey into the real world, where she will have to live without her comforts. So much pink paint has been used to paint the set that the industry is in crisis worldwide. Moreover, the doll is always depicted on tiptoe, a detail that the director strongly wanted in her film.

Accompanying her on this adventure are Ken (Ryan Gosling), and many other Barbies, including a mermaid Barbie, played by pop star Dua Lipa. She also curated the soundtrack, along with other artists such as Billie Eilish. One of the big names in the cast is Helen Mirren as the narrator. The film will also feature a previously unseen John Cena, as a merman, and some faces from Sex Education, such as Emma Mackey, who is credited with a strong resemblance to Margot.

From the Venus influencer to the inclusiveness of Barbie

From Greek statuary, through Renaissance art, women have always been subjected to unattainable aesthetic canons, after all, just think that Venus was a divinity. An extreme concept of beauty is therefore proposed that humans would not have been able to live up to. Botticelli’s painting is one of the iconic works of Italian art, so his Venus has been turned into an influencer to publicise Italy’s cultural heritage with the Open to Meraviglia campaign. An invitation to the dolce vita, demonstrating the power of beauty even centuries later.

Today, inclusivity has made its way into the concept of beauty and Gerwig’s Barbie is an example of this. Although aesthetically Barbie’s figure remains impeccable, the film shows that she is not perfect, that life has its difficulties and that beauty is not enough to cope with it. Margot Robbie restores a human dimension to a cultural phenomenon that is as incisive as it is distant from reality. The inclusive beauty praised in the film is a metaphor for the birth of a woman free from all canons. All that remains is to reflect on the journey of imperfection through beauties from different eras, from Botticelli’s Birth of Venus to the latest Barbie models.