After 45 years in the making, a single by The Beatles has been released. It’s the latest example of artificial intelligence‘s intervention in the music industry. In some ways, it’s a symptom of the trend towards digital necromancy in contemporary music: the use of AI to simulate or recreate the presence of deceased musicians, in this case, to have them create new tracks.

Now And Then is a track from ’78, well known to long-time fans. It had remained a demo on a tape that Lennon left to Yoko with the note “For Paul”. So, the intention of the piece seeing the light of day was already in the author’s mind. However, nine lustrums ago, he certainly could not have imagined that to achieve this, AI intervention would be necessary, initiated by Peter Jackson for the creation of the docuseries Get Back, for Disney+. And that later, the piece would be distributed on Spotify.

- Now and Then

- Artificial Echoes of Real Voices, with Lil Peep and XXXTentacion

- The Magical is Real: The Case of GPT-3

- Digital Resurrection in Music

- The Difference Between Analytical and Generative AI

- Imitations of Life: The Copyright Knot

- Necromancy in Pop Culture

- Sonic Specters and Real Ghosts

- Spectrality in Music

- The Uniqueness of Sound

- Retromania for the Future?

Now and Then

The demo was worked on by including the solo recordings that George Harrison had tried to write in the mid-90s, before the Liverpool trio decided to abandon the project due to the poor quality of the original recordings. At the time, they managed to successfully complete Free as a Bird and Real Love, starting from Lennon’s demos. In this case, however, it seemed impossible because his voice was muddled. Covered by the piano line, it seemed inseparable.

It was the AI that allowed for a thorough cleaning and restoration work, nothing more. Ringo Starr wanted to make this clear:

We’re not pretending anything. That is actually John’s voice, Paul’s voice and bass, George on rhythm guitar, and me on drums.

Yet Lennon’s voice was partly reconstructed by an artificial intelligence. This raises the question: where is the boundary? When does manipulation become digital necromancy? It’s the paradox of Theseus’ ship that questions the identity and continuity of an object despite changes: if all parts of a ship are gradually replaced, is it still the same ship?

An artificial intelligence can intervene to separate a voice from another line and clean it, certainly. But is it mere restoration when a machine learning system completes missing parts of the recording with frequencies generated anew?

Ringo added:

It was the closest thing to having him back in the room with us, so it was very intense for everyone […] It was as if John was there. Incredible.

This is one of the spectral potentials of digital necromancy.

Artificial Echoes of Real Voices, with Lil Peep and XXXTentacion

The issue of digital necromancy is pressing and needs to be addressed urgently. Recently, Liam Gallagher praised a fake Oasis album generated by artificial intelligence by an underground band. Grimes has given permission to fans to use her AI-generated voice in their music projects. ‘Just don’t make me sing a Nazi anthem,’ she commented.

The British magazine NME has explored the issue, reassuring about the proliferation of artificial intelligence in music. The thesis is simple: if a large supply of artificial music is created, there will be a large demand for human music. Although it’s early to speculate on the repercussions that such a tool will have on an already fragile market, it would be useful to investigate the growing tendency to keep the dead on Earth and make them sing for us. Lennon wanted the piece to see the light; probably Harrison less so. In any case, McCartney and Starr made the decision for everyone. This does not happen with many fan-made online productions, created for pure entertainment. At other times, however, it happens with productions directed by the majors, like the unintended epitaph of Falling Down by Lil Peep and XXXTentacion.

The Magical is Real: The Case of GPT-3

What was a decade ago an episode (S02E01, Be Right Back) of Black Mirror has long been a reality. In 2020, Joshua Barbeau programmed a version of GPT-3 with all the recorded conversations of his deceased wife Jessica, who died eight years earlier. Now, in the USA, companies like Somnium Space and Deepbrain offer the possibility to create a copy of oneself to stay in touch with loved ones after passing away. These digital meta-specters manifest in unexpected and surprising forms. Like true specters, they lurk in the most hidden and secretive nooks.

Digital Resurrection in Music

The concept of spectral absence pervades liminal spaces, and there is extensive literature on this (the idea that in transitional spaces, the absence of something or someone can be strongly felt). But how does this reflect if the dead produce art? Or rather, if artificial intelligence creates art using the deceased through forms of digital necromancy?

Some artists already seem immortal through their music, but this is a completely different matter. With emerging AI models, a few years ago, fans reinterpreted the voices of deceased musicians in new songs: Freddie Mercury singing on George Michael‘s Careless Whisper and Michael Jackson attempting Avicii‘s Wake Me Up. But these AI models are not just imagining a universe where music greats lived long enough to spend the last years of their careers doing karaoke of dubious taste. In the case of The Beatles, it’s an official piece, part of Lennon’s real production.

The Difference Between Analytical and Generative AI

“In general, we distinguish between analytical and generative uses”, explains Dr. Tom Collins, a lecturer in music technology at the University of York. Analytical AI, the more traditional form, is used to analyze existing data to help in prediction or automation. This means it can be useful for purely manual tasks. Generative AI, on the other hand, is capable of learning from data and then creating new data from its findings. The AI used for the restoration algorithm of Lennon’s demo is a mix of the two. It’s generative AI, the kind that mimics timbres and is, for example, at the heart of virtually all viral TikTok covers and is witnessing rapid development thanks to increasingly powerful computers.

Tyler, the Creator has been explicit in his desire not to be reincarnated by AI after death through digital necromancy. Similarly, Ice Cube called Heart On My Sleeve, an AI-generated duet between Drake and The Weeknd, “demonic” and urged Drake (who, by the way, released a “duet” in 2018 that included unreleased voices of Michael Jackson) to sue the creators. The song was subsequently removed by Universal Music Group. But as pioneers of an uncharted territory, there is still no real legal and ethical reflection.

Imitations of Life: The Copyright Knot

Without coherent rules and guidelines to define what is allowed or not, virtually anything can be done with AI. Theorists like Nick Bryan-Kinns, professor of Interaction Design at Queen Mary University of London, seem rather calm about future scenarios. After all, he says, the legend surrounding artists resides in what they were as living beings and how this translated into their songs.

AI simply does not have the same lived experiences as a human […] It has never fallen in love nor felt the emotion of watching a sunset. It hasn’t gotten drunk and never had a hangover. So it will probably be a bit boring.

This was perhaps valid in the past. Recreating a dead person is not so much an AI problem, on paper, as it is an issue of access to data on their memories, their words, their way of expressing themselves and living. If this can be a problem for people who lived forty years ago, due to the lack of an archive, today a cell phone tracks everything.

Once brought back to life, however, it will be necessary to decide who will own the rights to use the living dead; whether it will be record labels, companies, or families who can lease it out.

Necromancy in Pop Culture

Popular culture has always been fascinated by the idea of regenerating the dead, exploring the complex dynamics and ethical dilemmas surrounding mourning. Works like Stephen King‘s Pet Sematary and the 2015 film The Lazarus Effect investigate the repercussions of bringing loved ones back to life, raising questions about the emotional weight and moral implications of manipulating death. Absence is a personal and complex, human experience. The desire to reconnect is just as much, but it is legitimate to wonder what the consequences might be if we delegate the answer to machines.

Does digital necromancy provide a way to overcome death or simply makes it eternal? It’s not easy to distinguish whether it’s about the capacity to change the future or represents a form of stagnation in the past that begins to prey on the possible even after exhausting what was alive in it.

Initially, it was Gen Z, the same generation that adores series like Stranger Things which stimulate nostalgia for a time they never lived, who used new technologies to resurrect dead artists through unbalanced mashups; a surprise for scientific communities. But it’s not just a creative turn, like the sampling of 50s soul riffs in the 90s. What is brought back to life by reusing a voice is the social, political, aesthetic, and emotional capital of an artist.

Sonic Specters and Real Ghosts

It’s primarily a symptom. The way we deconstruct and reinterpret the art of our predecessors is part of the endless dialogue that music allows us to create. But there are two elements here: where does this desire for resurrection come from, and what value does a product of a machine with essentially a predictive model have. What do we do with something that a dead person “didn’t say, but could have said”?

After exhausting the fun that can come from asking questions like “What would it be like if Kurt Cobain sang in the Shrek soundtrack?”, digital necromancy raises multiple issues.

Spectrality in Music

First of all, one must consider that ghosts have always been fashionable. It’s a somewhat primordial notion, the belief that spectral visitors bring premonitions and omens is something that crosses all cultures and dates back to the dawn of human history. Subsequently, one might somehow argue that music is inherently spectral. Due to the invisibility of sound or the way certain melodies haunt us for days, whether we want them or not; the madeleine-like power of certain harmonies or motifs to instantly unlock our memories like a sonic Proust syndrome.

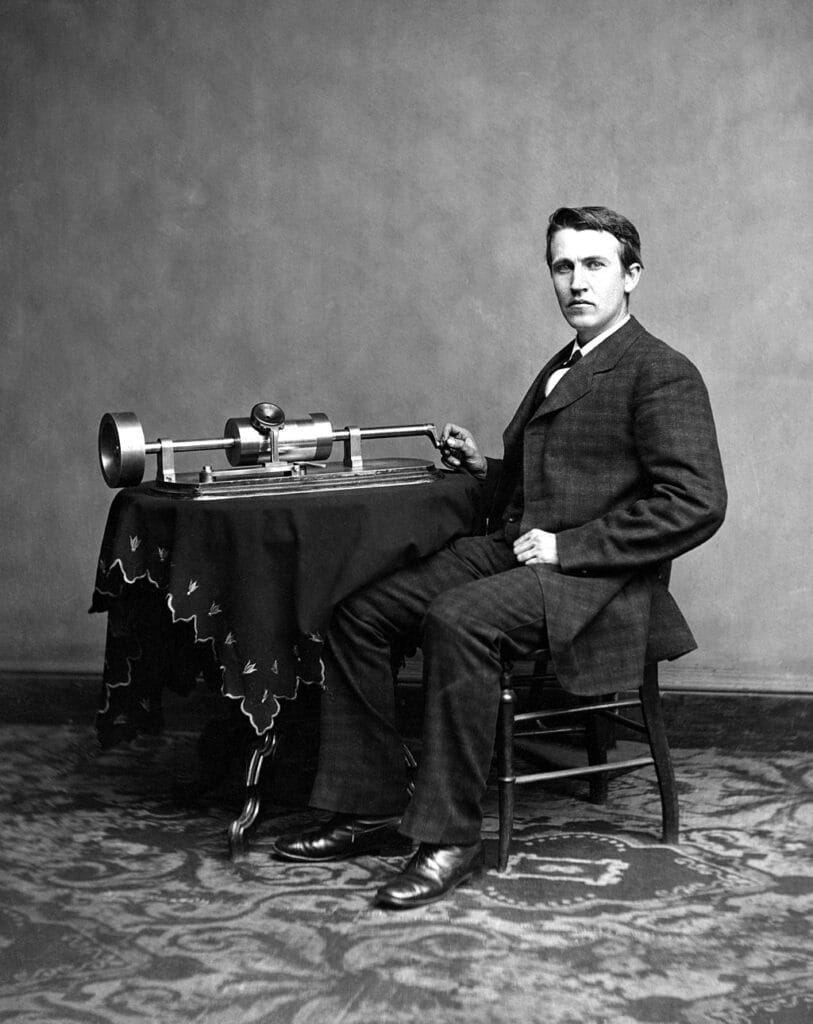

Another aspect concerns the spectrality of the recording itself: originally, Thomas Edison conceived the phonograph as a way to preserve the voices of loved ones after their death. Records have accustomed people to living with ghosts. Record stores are necropolises of vibrations. The public frequents absent presences, the immortal but dead voices of the phonographic pantheon, from Janis Joplin to Chester Bennington. One of the qualities these ghosts didn’t have, however, was to say new things. Until now, the forms had been those of sound taxidermy: these stuffed animals were not capable of moving, breathing, and imitating life.

The Uniqueness of Sound

The same kind of spectral approach was already present in the television medium, in film libraries and archives. In prime-time marathons that commemorate a recently deceased actor, they make them appear as if they are living and breathing throughout the night. Television can be unsettling, perhaps even more so than music, as explored in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983). The word shares the prefix tele (from afar, imaginative) with telekinesis, telepathy, and other paranormal phenomena. A dream machine.

But if humans are becoming increasingly desensitized to images due to the sheer volume of stimuli, music maintains its preeminent phantasmagoric quality: being invisible, passing through walls, and making objects vibrate. We’re not talking about a specific genre of music designed to have spectral notes, like Simon Reynolds‘ hauntologic and eldritchronic. These are ghosts that confuse our perception, crossing the uncanny valley of our defenses to stir real emotions.

Retromania for the Future?

There are many ghosts around. When a great artist leaves this planet, they transform into an icon. The first thing done is to try to release some unpublished piece, record an unexpected featuring with the help of artificial intelligence, and halt the present. This is a significant turning point in our perception of time and future prospects.

To quote Reynolds, in Retromania:

Rock/pop has reached that advanced age – late forties, early fifties, depending on when you date the beginning of the era – where it has more life behind it than ahead. It’s as if the sheer drag caused by the mass of its own corporeal memory had blocked the forward movement of pop, inducing a kind of temporal implosion: the endless retro black hole.

Simon Reynolds, Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, 2011

If we are trapped in the eternal present that cannot generate anything new, condemned to reiterate echoes of the past, a possible strategy might be – contrary to the accelerationism of hyperpop – a reinvention or rewriting of history. Reynolds adds, given the unauthorized absence of the Future, those with radical instincts are forced to investigate the past. Renegade archivists, they seek to discover secret alternative pasts within the official narrative, a pioneering strategy that now AIs seem to unlock with the new persuasive charm of digital necromancy.

No, John Lennon is still alive and we can reason in the present about the revolutionary impulse of the 60s. Kurt Cobain is still singing and we can maintain that nihilistic energy as an uncontrollable and visceral reaction to the contemporary. Discovering the “future in the past”, the return of all the musical nostalgia, from the return to the 70s avant-garde of much of the underground electronic, to the 80s pop nostalgia of much of the light music. It is not just nostalgia, but an attempt to return to past perspectives. More than a Proustian search to recover lost time, it’s about going back in time to change the future.

How this sentiment will soon impact artistic productions is all to be seen, and the possibilities increase with the unstoppable advance, at least on paper, of technology. Meanwhile, machine learning has brought us the last Beatles song in which they all played. At least, the last one recorded while they were still alive.