Arturo’s Island | Elsa Morante’s Poetic Journey into Youth and Loss

Length

From its first pages, Arturo’s Island immerses the reader in a world where the sea shines with “an indifferent splendor” – at once enchanting and relentless. Here lies the essence of Elsa Morante’s masterpiece: a novel that mesmerizes with lyricism while exploring solitude, desire, and the painful awakenings of adolescence. Published in 1957 and awarded the Strega Prize, the book stands as a landmark of Italian postwar literature, offering a vision of youth at the threshold of myth and reality.

Through Arturo’s eyes, readers witness the fragile architecture of ideals, the collapse of illusions, and the bittersweet necessity of leaving home behind, even as the island itself remains forever imprinted on the heart.

A Boy Among Waves and Rocks

Arturo grows up in Procida, a small island off Naples, in the shadow of a dead mother and an often-absent father. His house, the Casa dei Guaglioni, carries a dark superstition: women who live there are doomed to die young. Arturo spends his days roaming the island, master of his boat and of the sea, dreaming of heroic adventures.

When his father returns with a young bride, Nunziata, Arturo’s sense of himself and of his family is unsettled. She both disrupts and softens him: baking him cakes on his birthday, she becomes the maternal presence he never had, yet the patriarchal worldview lingers. Morante does not absolve Arturo; she exposes his confusion and inner struggles, as he navigates a world shaped by patriarchal expectations and machismo.

Procida: Dreamscape of Eternal Summer

Procida is not merely a setting; it is a character in its own right. The island appears like the stage of a Midsummer Night’s Dream, a celestial season where earthly beauty reaches its peak. The author renders its cliffs, caves, salted wind, and endless water with lyrical descriptions that verge on the fantastic.

For Arturo, the island is both home and kingdom. He is its young ruler, free to sail along its shores, to wander across rocks and fields, to feel invincible. As childhood fades, he faces the ache of departure, the impossibility of watching one’s birthplace become distant:

I don’t want to see Procida disappearing, turning gray (…) I’d rather pretend it never existed. So, until it vanishes completely, I won’t look back.

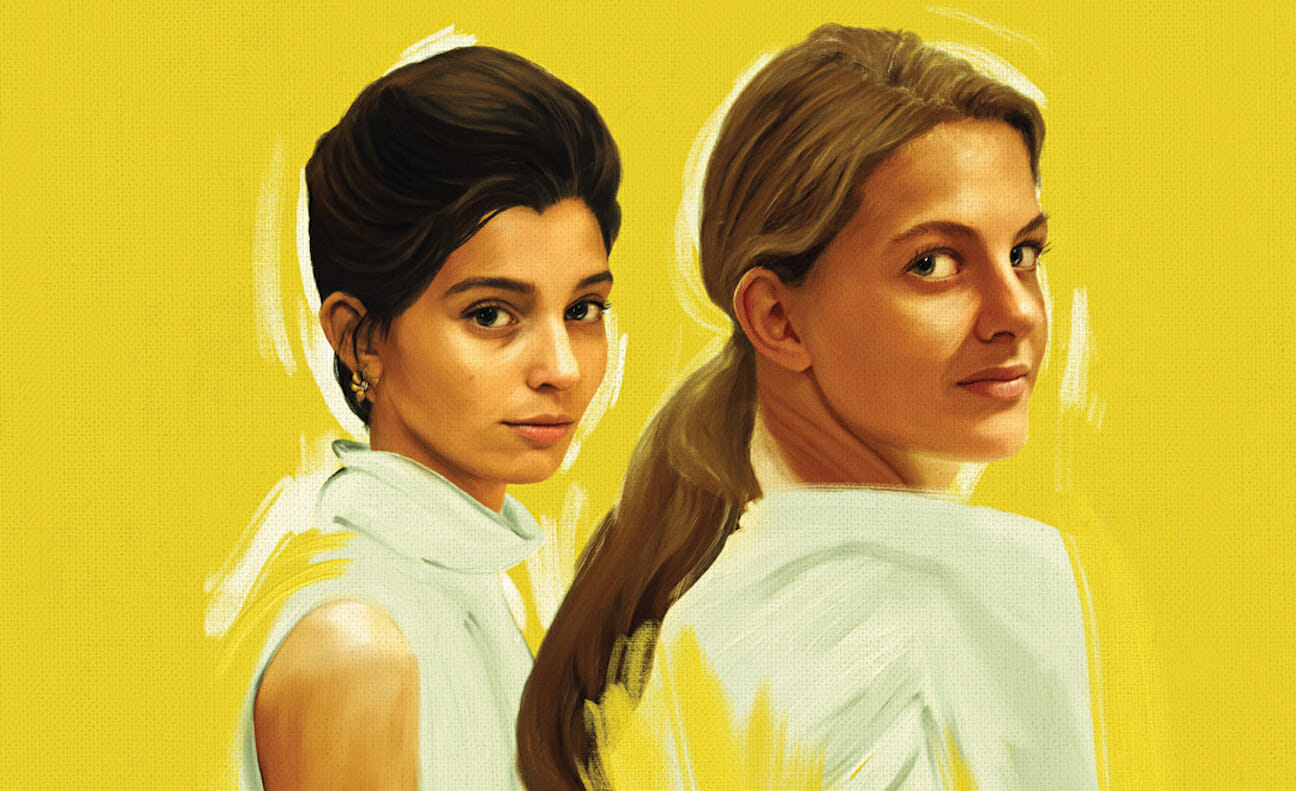

Arturo’s Island

Names, Heroes, and the Dissolution of Myths

One of Arturo’s earliest prides is his name:

One of my first prides had been my name … Arturo is a star: the fastest and brightest light in the constellation of Boötes (…) and also the name of an ancient king, commander of a band of heroes, who treated them as equals, as brothers.

Arturo inhabits these myths, comparing himself to figures from Greek tragedies, such as Oedipus, Achilles, and Odysseus. His father, Wilhelm, initially appears godlike, remote, celestial. As Arturo matures, he begins to see himself as a flawed human being, capable of mistakes. The collapse of paternal myth is the novel’s most intimate tragedy: no human, not even a father, can live up to the grandeur of epic.

Women, Superstition, and the Weight of Machismo

The Casa dei Guaglioni is shadowed by superstition: women who enter are believed to be doomed. Arturo grows up motherless, haunted by absence, and seeks maternal care in his stepmother, Nunziata. She disrupts and softens him at once, offering warmth he never knew. Yet the relationship is complex: Arturo experiences both the comfort of a maternal presence and the stirrings of first love.

Arturo grows up in a culture that diminishes women. He observes:

According to my father’s judgment, real women possessed no splendor and no magnificence (…) they went around like sad animals.

Patriarchal and southern cultural beliefs shape his perception of women as weak, burdensome, and, sometimes, dangerous. Morante portrays his confusion and longing with honesty, showing how absence, superstition, and machismo shape the formation of desire, love, and moral judgment.

Morante herself once said she wished she had been born a boy, aware of the freedoms and privileges this might bring. When she said, “Arturo, c’est moi”, she identified with his agency and courage, exploring adolescence, desire, and ambition from a perspective she longed to inhabit.

From Morante to Ferrante: Literary Mothers and Daughters

Morante’s ambivalence toward maternal figures in her romance did not prevent Italian feminists from claiming her as a symbolic mother. The Collettivo delle Librerie delle Donne di Milano described her as “one of the mothers of us all” in 1982.

Elena Ferrante, her most famous literary heir, often credits Morante with legitimizing her bold, unflinching portrayals of female desire and imperfection. Ferrante’s Naples recalls Morante’s Procida: both spaces of poverty, violence, superstition, and family secrets. Natalia Ginzburg, another towering figure of the same generation, admired Morante above her peers. Together, these authors mark a lineage of Italian women’s writing that is now increasingly recognized in English translation.

Finally, Arturo’s Island traces the beginnings of selfhood and the end of childhood, the beauty of belonging and the pain of departure. Morante gives us a boy who loves too much, dreams too intensely, and must confront the impossibility of myth surviving reality. Procida may fade on the horizon, but it remains indelible. Morante’s vision of adolescence – at once cruel, luminous, and unforgettable -continues to speak across generations, as if each reader were boarding that ship alongside Arturo, carrying an island within.

Tag