Diabolik | The King of Terror

Year

Format

By

‘I am a murderer, Eva. If I need to, I kill. And that leaves me completely indifferent.’

Diabolik, from L’isola degli uomini perduti (The island of lost men)

Diabolik, the masked man whose real name is still a mystery, was born in Italy from the mind of Angela Giussani.

History has it that at that time, in Turin in 1958, there was a murderer who, after writing to the local press, had started calling himself Diabolich. He was never caught. There are those who think that the inspiration for the comic (especially for the name) comes from here, or perhaps from the character of Fantômas, the famous and ruthless criminal protagonist of the homonymous novels.

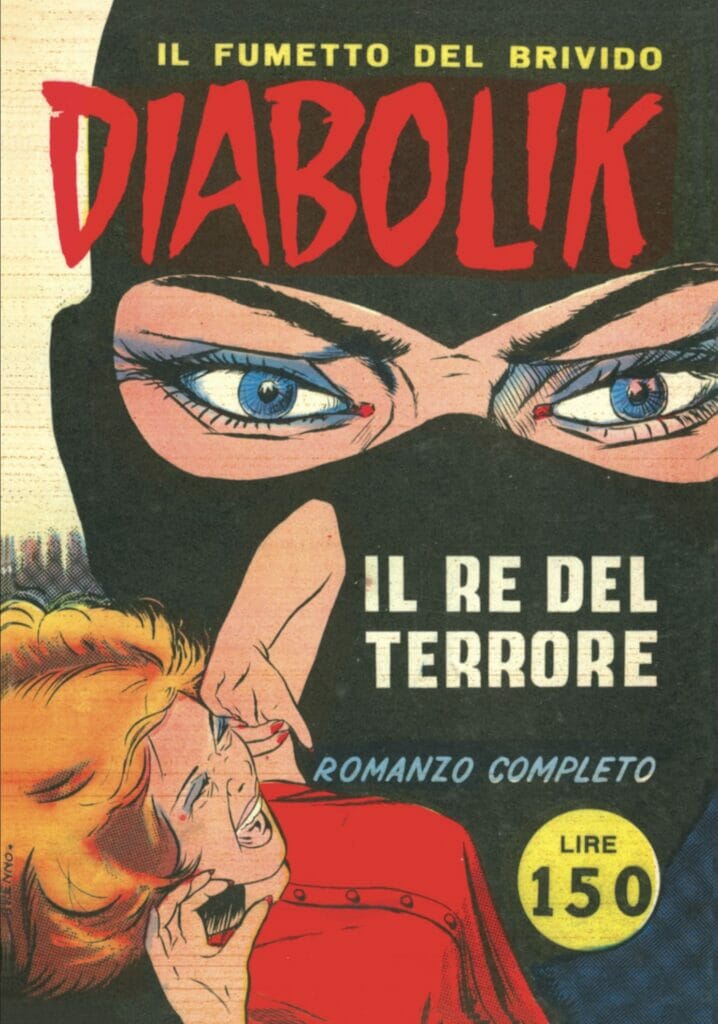

But the fact is that when Diabolik saw the light on November 1st 1962 with Giussani’s publishing house, Astorina, other comic book publishers observed its birth with a wry and amused smile: they didn’t believe that a ruthless criminal would be successful. History proved them wrong.

The King of Terror

Up until Diabolik, Italian comics were more akin to what might be called ‘boys’ stuff’. Giussani, on the other hand, wanted to conquer a more adult audience, bearing in mind the newborn success of adventure novels with romantic subplots. Astorina then published Diabolik in a pocket format, smaller than the other comics, so that commuters – adults – travelling for work could carry it easily.

But the main characteristic of Diabolik was a new type of character, which created a new genre of comics, at least in Italy: the so-called fumetti neri, or black comics. This term refers to those comics in which the protagonist is an anti-hero or a criminal, and their stories therefore see a reversal of morals with respect to the common dictats of real society. Compared to the American comics, Diabolik could then be a more ruthless and morally compromised Batman.

With Il Re del Terrore (The King of Terror), the first issue, all of this quickly became clear. Diabolik is a thief who, in the imaginary city of Clerville and its surroundings, doesn’t steal from the rich to give to the poor, but to return to his lair with his loot. His is more a challenge against himself and the law, to show that he is the smarter between him and his nemesis, the police inspector Ginko. And, if someone gets in the way of his work, Diabolik has no problem killing them in cold blood.

Naturally, he has a code of honor that he follows slavishly, but he’s mostly a murderer and a criminal mastermind, and readers have always found it fascinating to read about how he would carry out his umpteenth heist, thanks also to the help of his technological devices and his masks, constructed so as to be able to assume anyone’s identity.

The social reaction

Such a character could not help but trigger a number of controversies. There have been a variety of allegations, such as inciting violence and even disturbing the souls of readers. The corruption of minors, incitement to commit crime and obscenity are just some of the complaints that have been made against the creators of Diabolik. It was as if, to a superficial eye, nowadays one genuinely rooted for the stalker protagonist of the TV show You.

Diabolik has always been, in the minds of its creators, the expression of what is wrong in society, especially within the bourgeoisie (to which Diabolik and its authors also belong), whose ideology is based on consumption and accumulation. Diabolik shows a side of this social class in a way that evidently not everyone liked: being merciless and dominating at the expense of the weakest.

By 1964 Angela Giussani’s sister, Luciana, worked as an author at the Astorina publishing house as well, and the two had always pushed ahead regardless, overcoming negative opinions and letters from lawyers. They had no intention of changing their character.

The arrest of Diabolik

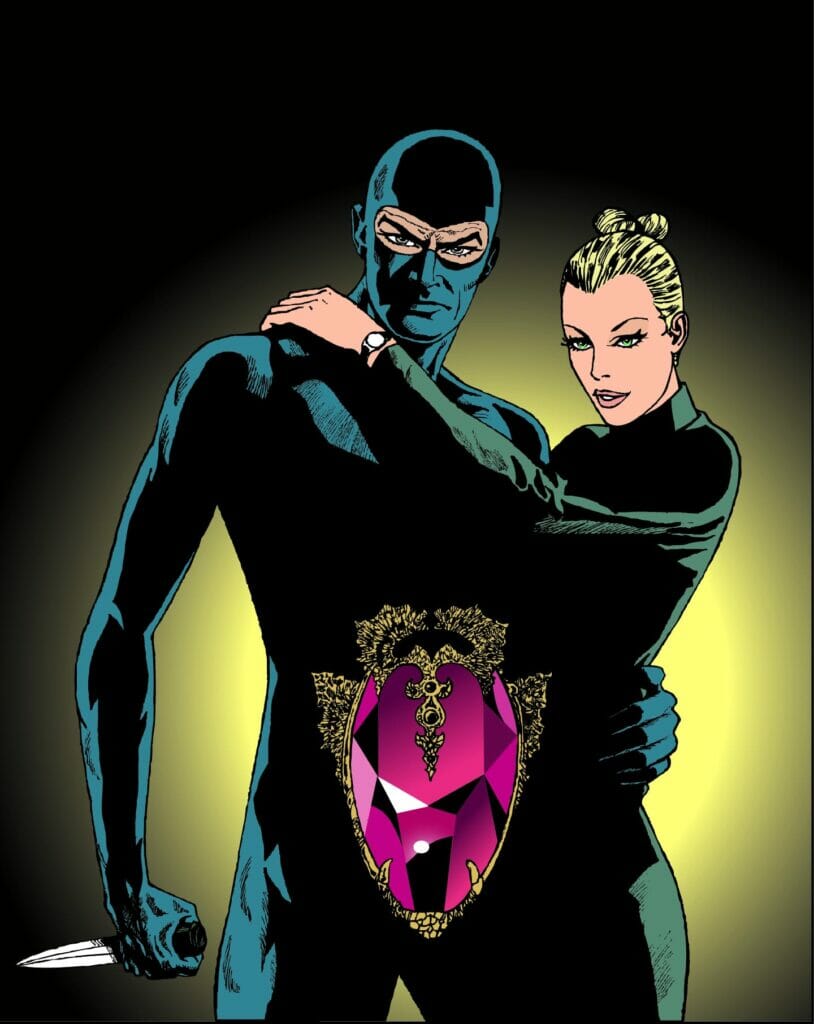

When one thinks of Diabolik, the person that springs immediately to mind is his partner, Eva Kant. The widowed woman, who married her cousin only so as to be able to recover her family name, is introduced in the third issue in 1963. Called L’arresto di Diabolik (The arrest of Diabolik), in this issue she saves the criminal from the guillotine. Obviously, of course, the two then flee together.

As Mario Gomboli, current director of Astorina, said in an interview for AudibleBlog, “Diabolik’s a thief and a murderer, yet he knows how to be sweet and sensitive with his partner, to whom he’s strictly faithful. Eva Kant is a determined woman, strong and ruthless when needed. She suffers the charm of her companion but is not dominated by him.”

Eva is a woman of extreme beauty, but has never been Diabolik’s subordinate. She isn’t the protagonist (although she takes center stage in many stories), but she has always had an equal relationship with the criminal. Indeed, when Diabolik tries to act superior, Eva never misses an opportunity to remind him they’re on the same level.

She has therefore subverted the canons of the comic book woman, often seen as a trophy, a victim or just a sweetheart. The same thing goes for their concept of a couple: they’ve never married and never had children. They define their love story as being perfect as it is, and in the 60s and 70s a de facto couple couldn’t but create a further stir. Diabolik has always tried to keep up with the socio-political context of the time, often even overtaking it. Just to mention one instance, in 1974 an issue included an illustration of Diabolik and Eva in which the characters themselves invited readers to vote NO on the referendum on the abrogation of divorce.

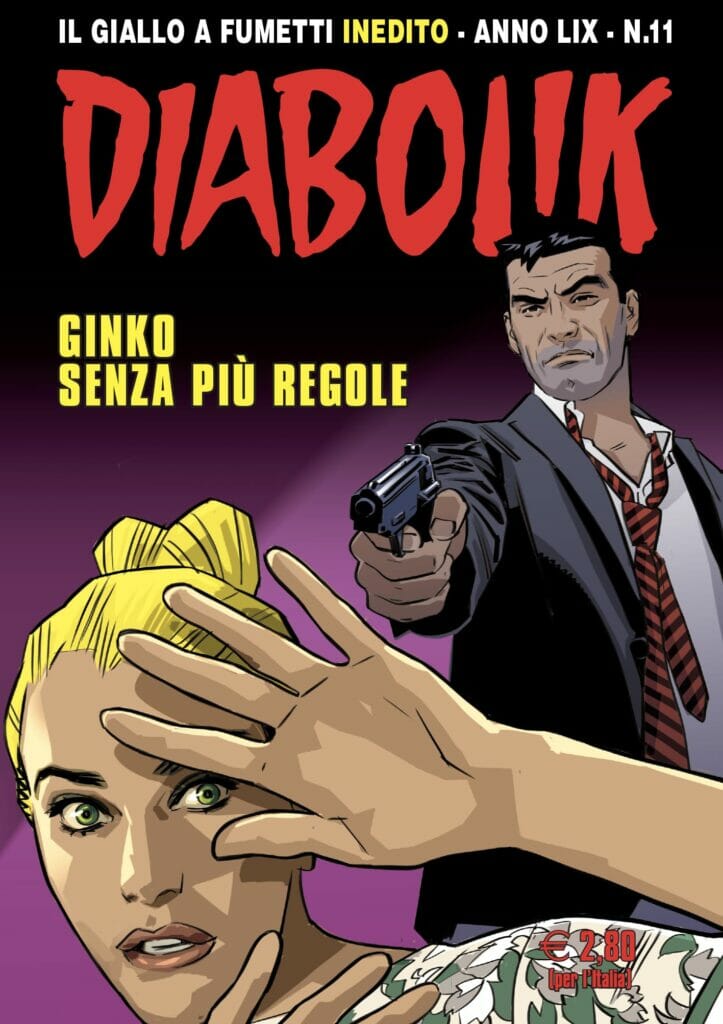

Ginko with no more rules

Someone has to hunt down both Diabolik and Eva, and his name is Ginko, the police inspector. Peculiar indeed is the use of the letter K in his name, a choice made to underline the bond that the policeman has with the criminal. In fact, the two are alter-egos of the same person, even in their lineaments: the American actor Robert Taylor inspired both their character design.

The concept is explored once more in 2020, with the issue Ginko senza più regole (Ginko with no more rules), in which the inspector finds himself manipulated and unaware of it: he faces a psychological journey that threatens to break his mind irreparably, forcing him to make gestures that he would later regret. It’s up to Diabolik and Eva to investigate what is happening to the inspector.

Diabolik doesn’t want anything bad to happen to Ginko. Their relationship is one between adversaries, not enemies. The criminal carries out his misdeeds precisely for the sake of adrenaline and being able to escape justice. If the one who embodies the values of justice was suddenly missing, there would be no more taste or excitement.

The relationship is like that which binds Moriarty and Sherlock Holmes, especially given that Ginko looked a lot like the latter, the more so at the beginning of his comics career. They certainly still have in common the never wanting to give up, a marked deductive intelligence and also a love for the pipe.

Diabolik, who are you?

Diabolik is still ongoing, with more than 900 issues up to now. Its publication has also extended abroad, in various countries on all continents. It has several films to its credit, including a trilogy still in progress (Diabolik, Ginko all’attacco! and Diabolik, chi sei?), video games, board games, novels, animated series, documentaries, exhibitions, and even a radio comic and an audio comic.

Since its inception, it has attracted acclaim and discussions. With the birth of fumetti neri, imitations and parodies have followed, from Satanik to Kriminal passing through Cattivik and Paperinik. Even in the United States, Diabolik inspired the cartoonist Grant Morrison for the creation of Fantomex, a member of the X-Men whose assistant AI has the name of E.V.A.

There will always be something to discover about him. In the 1968’s issue Diabolik, chi sei? (Diabolik, who are you?) the readers can discover something about Diabolik’s origins. He’s an orphan raised by a criminal called King. However, because even the protagonist still has no idea who his real parents are, there is still possible information to unravel.

Diabolik brings mysteries even in the real world. For example, the illustrator of the first issue, Angelo Zarcone, known as “The German”, disappeared into thin air. Not even the famous investigator Tom Ponzi, hired to find him for Diabolik‘s twentieth anniversary, managed to do it.

Over the years Diabolik has not remained the unscrupulous criminal he once was. His code of honor has strengthened and now his killings mostly focus on other evil criminals. But certainly, he still has a lot to tell about the society in which we live.

‘Diabolik will cease to exist when society no longer will need him to detect its contradictions.’

Angela and Luciana Giussani

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic