The Raven | Poe's study on paranoia

Author

Year

Format

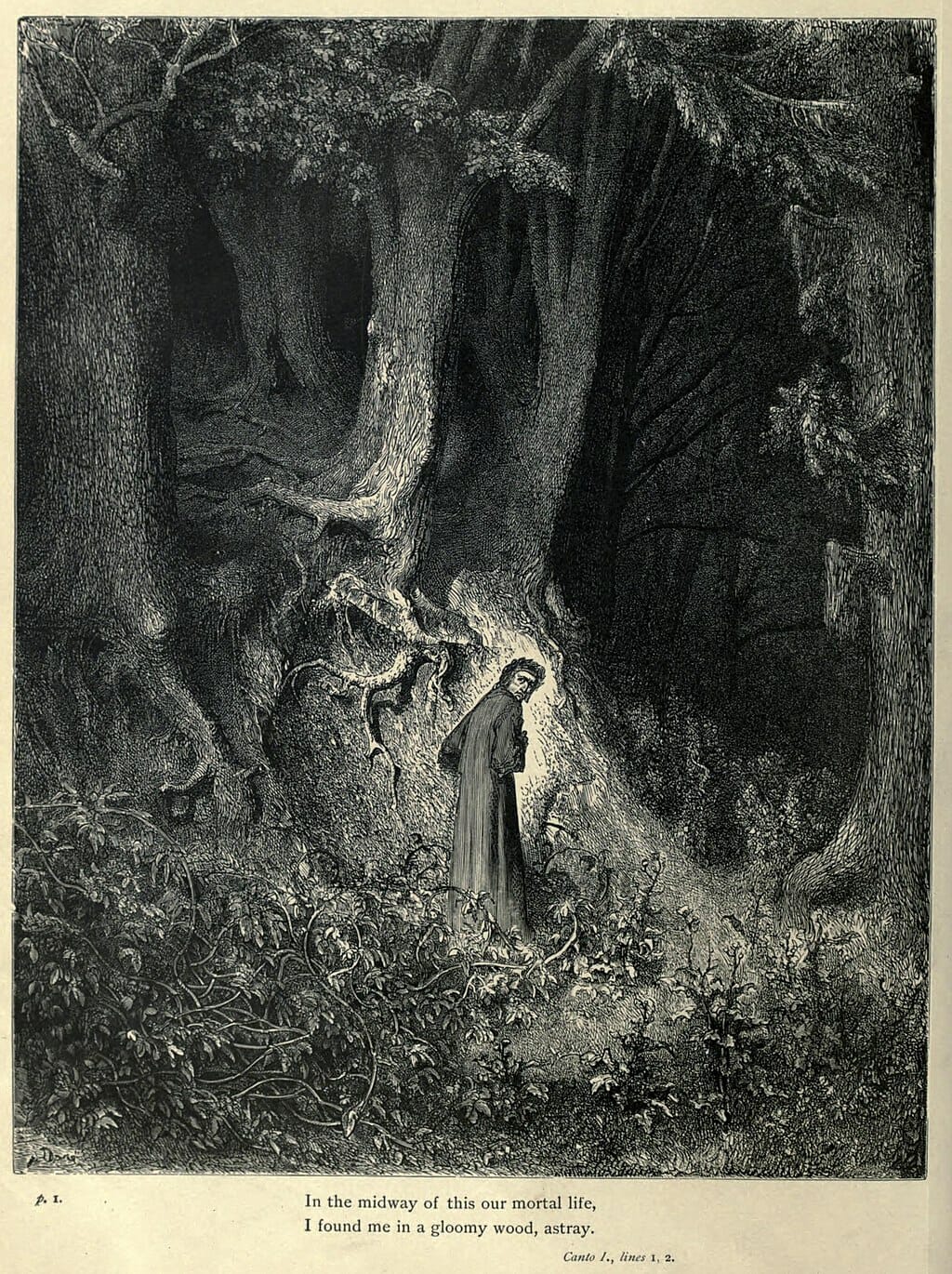

Midnight. A man is grieving the loss of his lover Leonore and reading an old volume. Suddenly, he hears noises coming from the front door. He believes it might be a visitor, but when he opens the door, nobody is there. In a hushed voice, he calls for Leonore. He comes back to what he is doing, but then the noises reappear. The second time he goes to open it, he finds a dark and ominous bird.

This is the gloomy opening of The Raven, a poem written in 1845 by Edgar Allan Poe. The rest of the poem is a dialogue between the speaker and the raven that only responds with one word: “Nevermore.”

A disturbing atmosphere

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

The Raven is a study on grief, guilt, and paranoia, three themes that are crucial in Poe’s literary production. Poe introduces the reader to a disturbing atmosphere: it’s late at night, it’s December, so it’s cold outside, and there is some recent sorrow hunting the man. The loss of Leonore in mysterious circumstances – the reader doesn’t know the reasons for her death – makes him fear a possible return. His anxious feeling is suspicious and arguably connected to guilt.

How obsession works

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

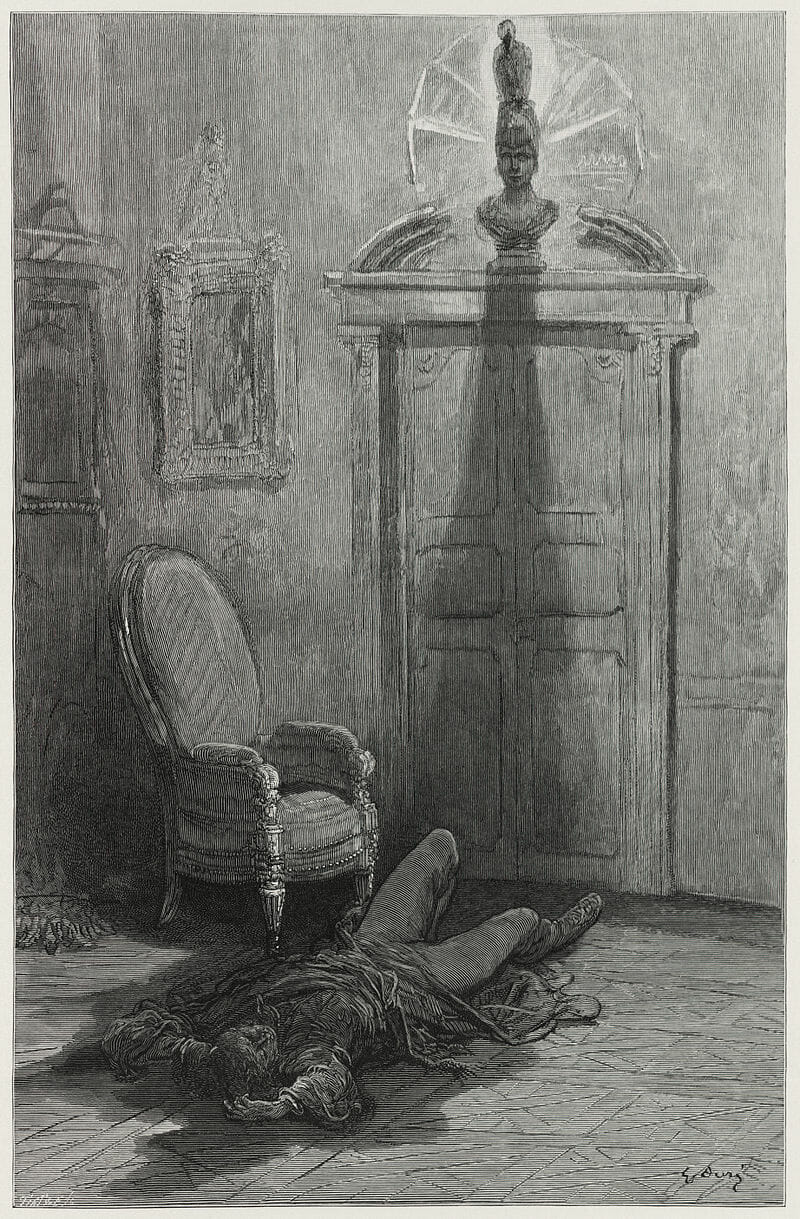

In Poe’s tales and poems, guilt is rarely about right and wrong. It’s a powerful force that operates from within an individual and drives him to self-destruction. The Black Cat and The Tell-Tale Heart are an example. To the man narrating, the raven is a prophet of an obscure future. But to the reader, it becomes the mirror of the secret fears of the narrator. Because of this, it becomes irrelevant whether the raven is a real presence or a hallucination.

At first, the man appears melancholic but rational: he considers logical explanations for the sounds he hears. However, the more he interrogates the raven, the more he slides into madness, interpreting the mono-response of the bird as a personal conviction. Obsession feeds on self-induced torture. The American writer Henry James perfectly depicted this idea in his horror tale The Turn of the Screw, where the screw is a metaphor for the slow penetration of paranoia.

A fecund legacy

Poe’s references in writing the poem were numerous, beginning with Charles Dickens‘ Grip in Barnaby Rudge, a clumsy raven reproducing human words and the sounds of many objects. Poe thought that Dickens didn’t manage to realize the full creepy and dramatic potential of the animal. In fact, in his poem, the raven becomes a thing of evil, the incarnation of horror.

The Raven left an immense heritage in the artistic world. For example, the Italian poet Giovanni Pascoli wrote L’Assiuolo (The Scops Owl) as a soliloquy to a sad bird’s call, inspired by Poe’s work. They both imbue the two-winged animals with a supernatural role. To Pascoli, the voice of the bird mirrors the one of the beloved people he lost. The use of onomatopoeia is different, though. In Pascoli’s poem, it’s the pure reproduction of a sound (chiù chiù), while Poe uses a meaningful word whose articulation recalls the cawing of a raven.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic