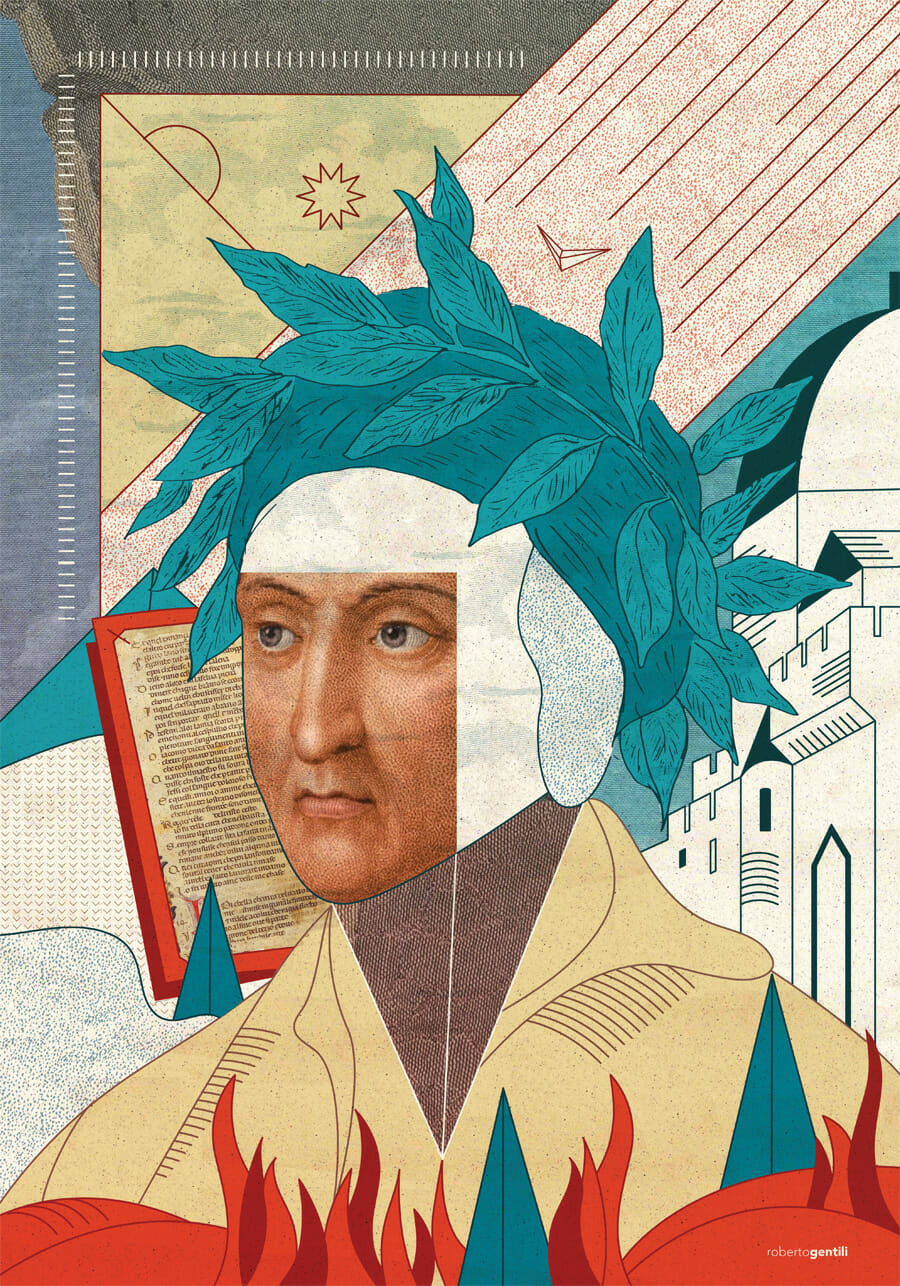

Doré and the horror vacui in Dante's Divine Comedy

Artist

Year

Country

Format

Material/Technique

Paul Gustave Doré was a French artist and printmaker, born in 1832. His body of work has succeeded in conditioning and influencing the Western world’s artistic perspective, gaze and imagination.

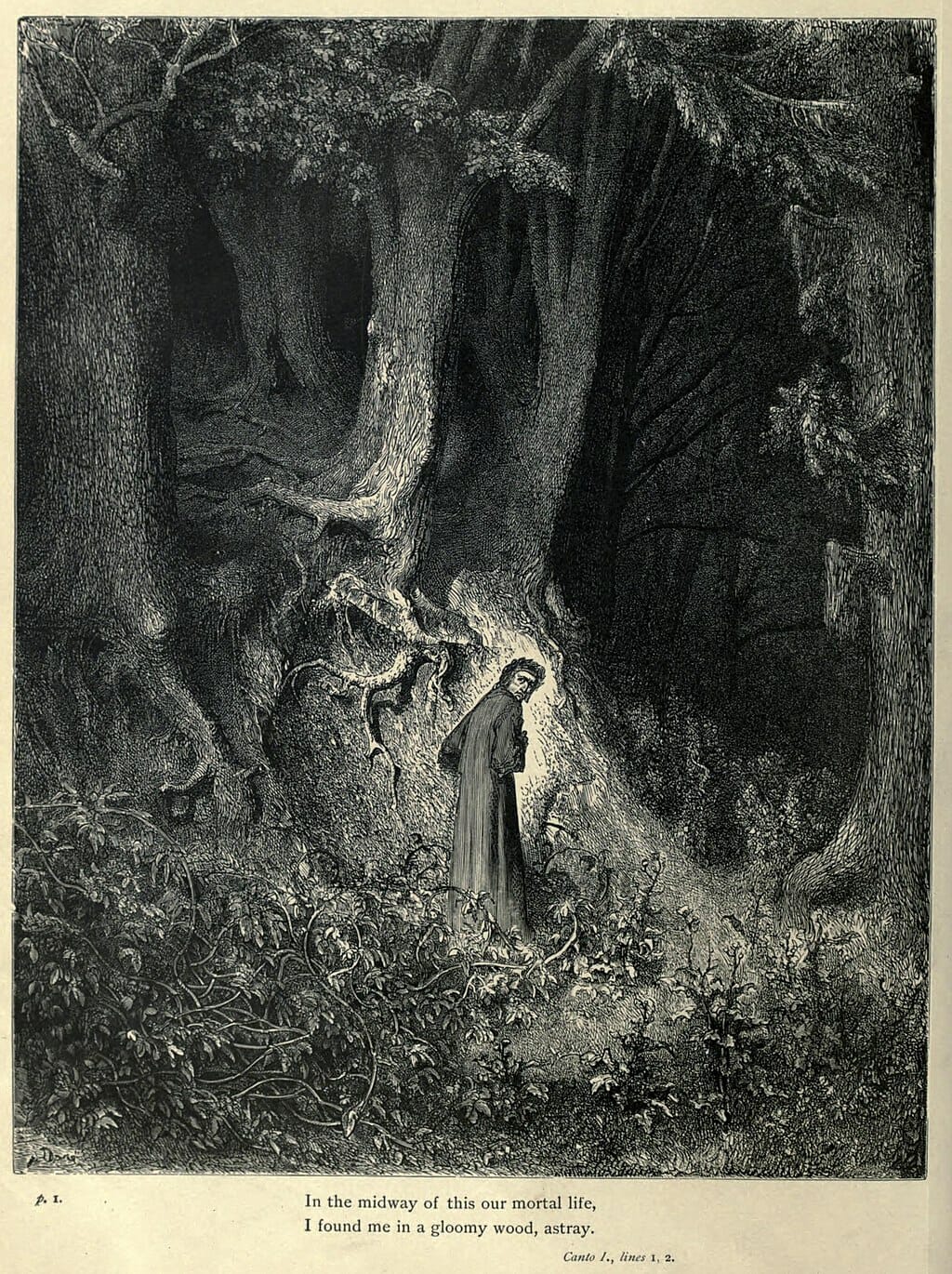

When Doré worked on Dante’s Divine Comedy, his fame was at its peak. His most remarkable ability is to immerse the viewer, who in this case is first and foremost a reader, in his world made up of landscapes that leave no room for emptiness. Doré shows with his illustrations the horror vacui in Dante’s Divine Comedy.

A career at its peak

His fame as an engraver and illustrator nearly damaged his career, when he attempted to try out other art forms such as painting and sculpture. He never received any artistic recognition for these techniques, as his contemporaries in the mid-1800s, especially the French, preferred his illustrations.

Doré reached the apogee of his fame by combining drawings and literature. His artistic fortune focused on the illustrations of texts by contemporary writers of his time, such as Honoré Balzac, Edgar Allan Poe, Alfred Tennyson, and great classic authors, from Dante Alighieri and Miguel Cervantes to Ludovico Ariosto.

He also illustrated the Bible, showing evidence of extreme compositional ability and great invention, proposing unpublished representations of passages from the Holy Scriptures.

Full-page illustrations

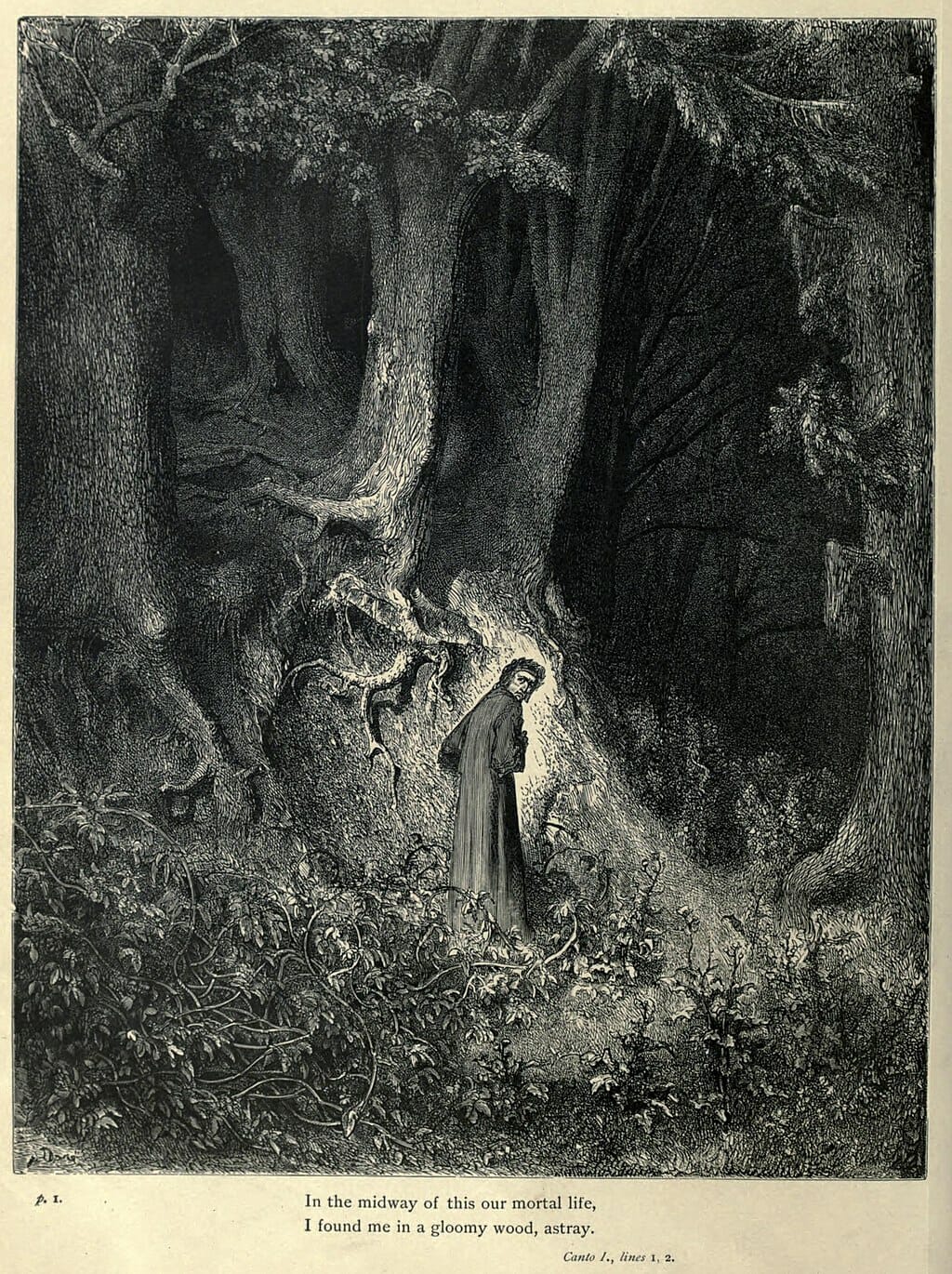

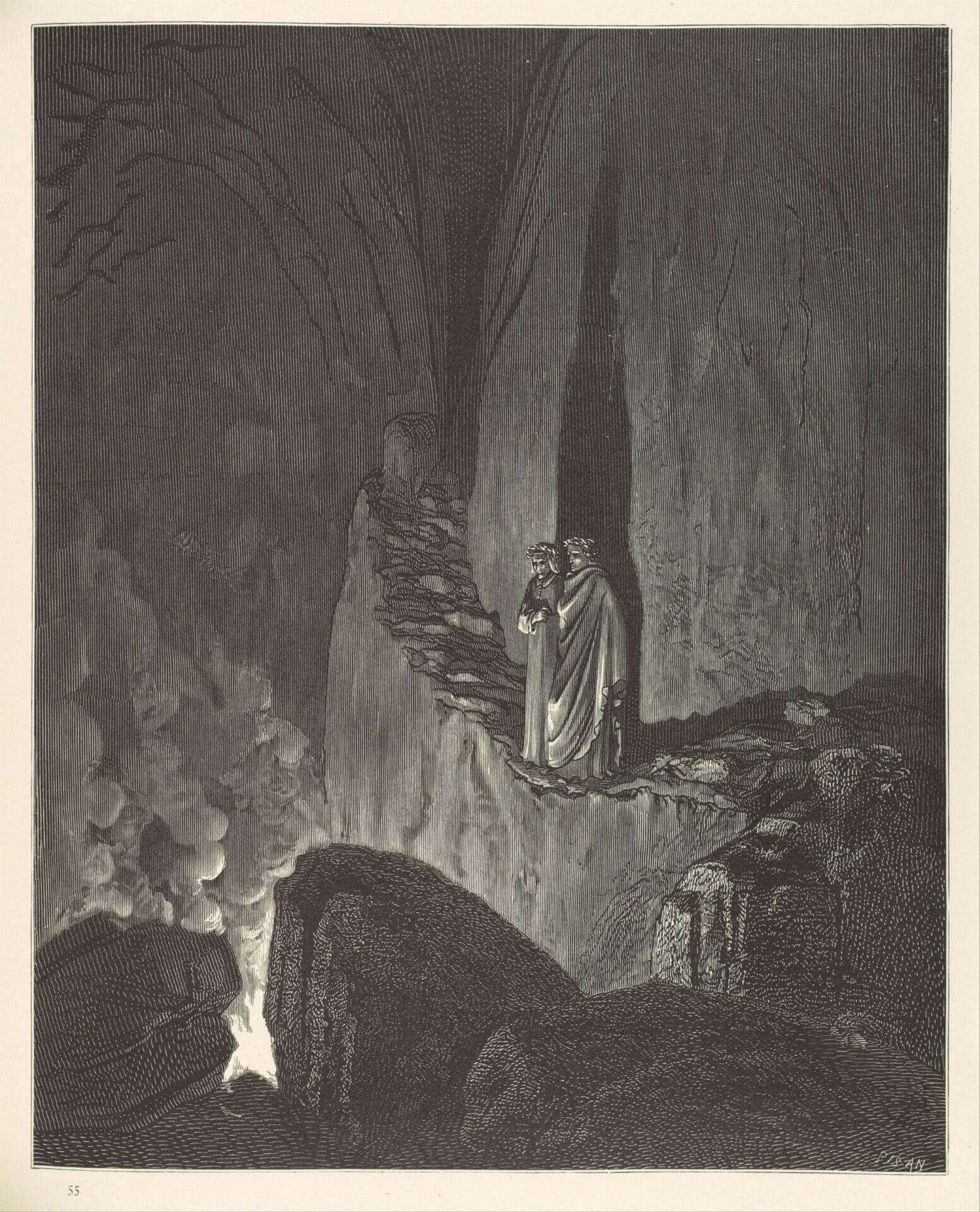

Doré’s landscapes are full. He leaves no trace of white in his pages, which he covers in dense forests, cloudy skies, and crowds of people. This horror vacui, as it is known, his fear of emptiness and the blank page, is a signature element that becomes in his works a ploy to orchestrate his scenes and guide the viewer’s eye. It derives from Aristotle’s idea that “nature abhors an empty space.”

In the First Canto of Dante’s Comedy, Doré leads the viewer’s gaze through the play of chiaroscuro in the background. In doing so, he exploits the verticality of the trees and the diagonal of the ground to highlight the Poet figure with a sort of lay halo. This element is a clear homage to the art of Tintoretto and Rembrandt.

Towards the climax

The way Doré organizes his illustrations’ elements is reminiscent of a chorus. He places each component carefully, composing a visual melody that points towards a goal, often the protagonist. It is as if Doré is playing the role of a conductor directing various voices and instruments toward a climax. This skill is reminiscent of Gioachino Rossini’s similar ability to create melodic and narrative tension by exploiting the chorus.

For example, in William Tell‘s finale, the composer bases the instrumental part on an endlessly repeating motif acting as a foundation, leaving no room for silence. From a succession of individual and different voices, Rossini builds the chorus that guides the audience to the finale.

What Rossini did in music, Doré realized in his illustrations, succeeding, like no artist before him, in rendering the concept of a finale in a clear visual way.

Tag