Monet and Mitchell | A dialogue about colors, nature, and feelings

Year

Country

Format

Original Exhibition

Exhibition dates

Material

The exhibition Monet – Mitchell, at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris until February 27th, 2023, creates, for the first time, a visual, artistic, sensory, and poetic dialogue between the works of two artists, Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Joan Mitchell (1925-1992).

The exhibition presents on one side the work of one of the most famous French painters, the father of Impressionism. On the other, the work of a female American artist, noted for her colorful bursts amongst the Abstract Expressionists.

Side by side, these two oeuvres and artists resonate, communicate, and debate. The similarities in Monet and Mitchell’s palettes and their brush strokes catch the audience. There are other common themes, such as the passion for nature and the landscapes, and the drive to transcribe the depth of human feelings.

This impossible debate between these two authors ends with the reconciliation of their works and philosophies, leading the viewers to new angles where they can rediscover Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism.

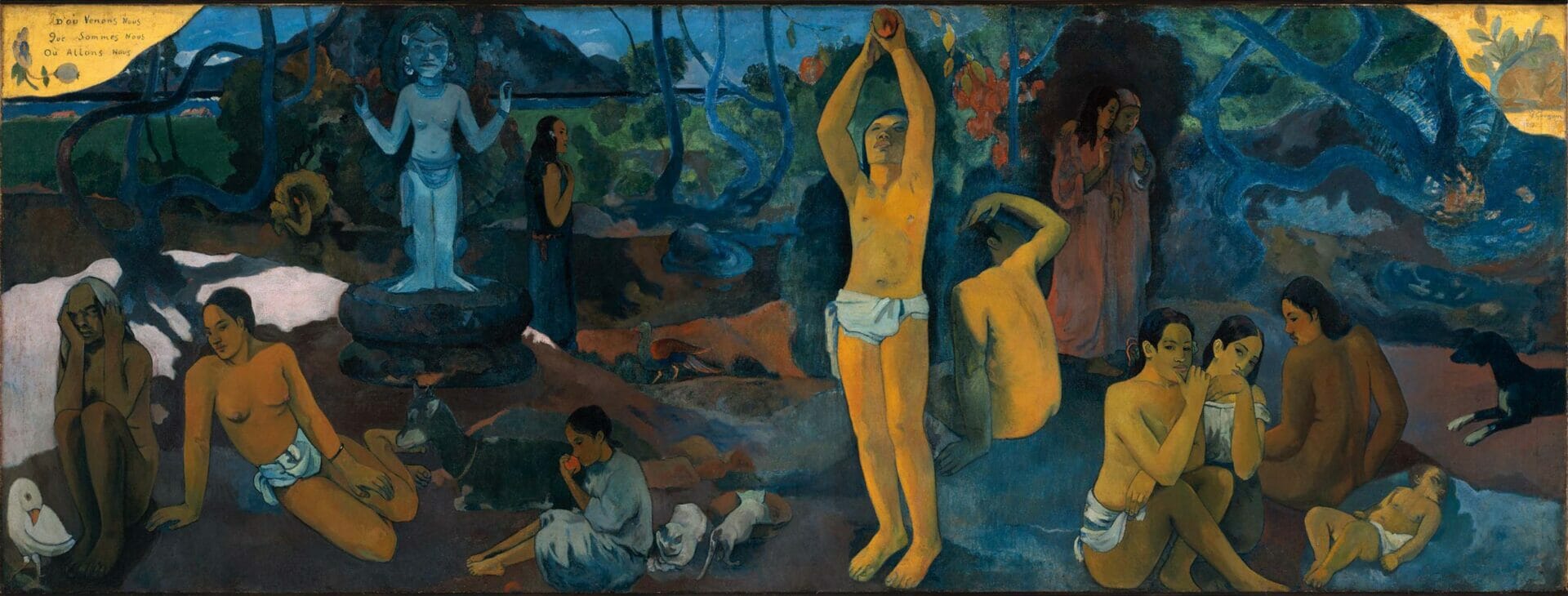

The world of Monet: light, colors and movements

The Impressionist movement gained its name thanks to Claude Monet’s painting called Impression, Sunrise exhibited in 1874, because the critic Louis Leroy accused it of only being a sketch or an impression. It is said that the rise of Impressionism was a response to the creation of photography: this new medium influenced artists interested in capturing the instant, snapshots of mundane and soft scenes of everyday life. Instead of competing with photography’s accurate representation of reality, Impressionists felt free to convey their perceptions of reality by focusing more on light, colors, and movements. Various stylistic trends stemmed from the initial group of the movement, allowing for instance Fauvism to appear with the work of Paul Gauguin.

Claude Monet, born under the name Oscar-Claude Monet in 1840, lived for most of his life around Paris. He also traveled to Normandy, Algeria, London, and Holland. With a sometimes difficult temperament, prone to anger and desperation, Monet was a hard-working artist and a gardener at heart, as his numerous series of paintings would attest. His oeuvre represents the triumph of Impressionism.

The world of Mitchell: jazz, gestures, and poetry

Mitchell’s artistic beginnings were shaped by the fervid atmosphere of New York City in 1950, taken over by jazz, painting, and poetry. At that time there appeared the gestural paintings of abstract expressionists. Also called action painters, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Franz Kline were the prominent figures of this movement. With them, the significance of the canvas changed, it stopped being the support, the background, on which events were represented, and it became the event itself. Kline and de Kooning supported Mitchell and invited her to exhibit in 1951 at the 9th Street Show. This exhibition was the post-war artistic happening that pinned down New York as a new cultural center on the map.

Joan Mitchell was born in 1925 in Chicago. She spent her life between the United States and France. Thus, she was not bound by the aesthetic constraints of Abstract Expressionism. In Europe, she encountered artists with a more lyrical style that resonated with her. Indeed, Joan was raised with poems told by her mother who was a poet and also deaf. As a result, poetry and rhythm remained a source of inspiration for her emotionally intense abstract work.

The common ground, a land of painters

The two individuals and their inspirations came from the same ground, the same land, a town, and a garden to the west of Paris. Monet stayed with his family in a house in Giverny from 1883 until he died in 1926. There, the artist imagined his garden and a pond around which he meticulously arranged endless blooming flowers. This closed and controlled environment allowed Monet to capture his surroundings more easily. As for Mitchell, she moved in 1989 to Vétheuil, close to where Monet’s former residency had been between 1878 and 1881. Indeed, from her terrace, she could oversee his house. Thus, she shared with him this elected view from Normandy, a setting that allowed the explosion of her talent.

However, Mitchell claimed total independence from her predecessor. She once said:

In the morning, specially very early, it is purple; Monet already demonstrated that… When I go out in the morning, it is purple, I am not copying Monet.

Joan Mitchell in a interview given to Suzanne Pagé, the general curator of the exhibition

According to Mitchell, if there are any existing similarities in their work, they were not signs of imitations not even mere coincidences, but the result of the variables provided by the same environment that was the same source of inspiration.

Claude Monet, The Artist’s House from the Rose Garden, 1922-1924 Oil on canvas, 81 x 92 cm

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris MONET, PARIS,

Nature whispering creativity

The eyes of the artists offer new ways to look at one’s surroundings. Notably because for these creative people, nature acts as a Muse. According to ancient Greek mythology, the nine Muses were the Goddesses of art, literature, and music. Muses whispered into the genius’ ear. Furthermore, Muses started as nymphs, creatures connected to fertile growing things such as water and plants.

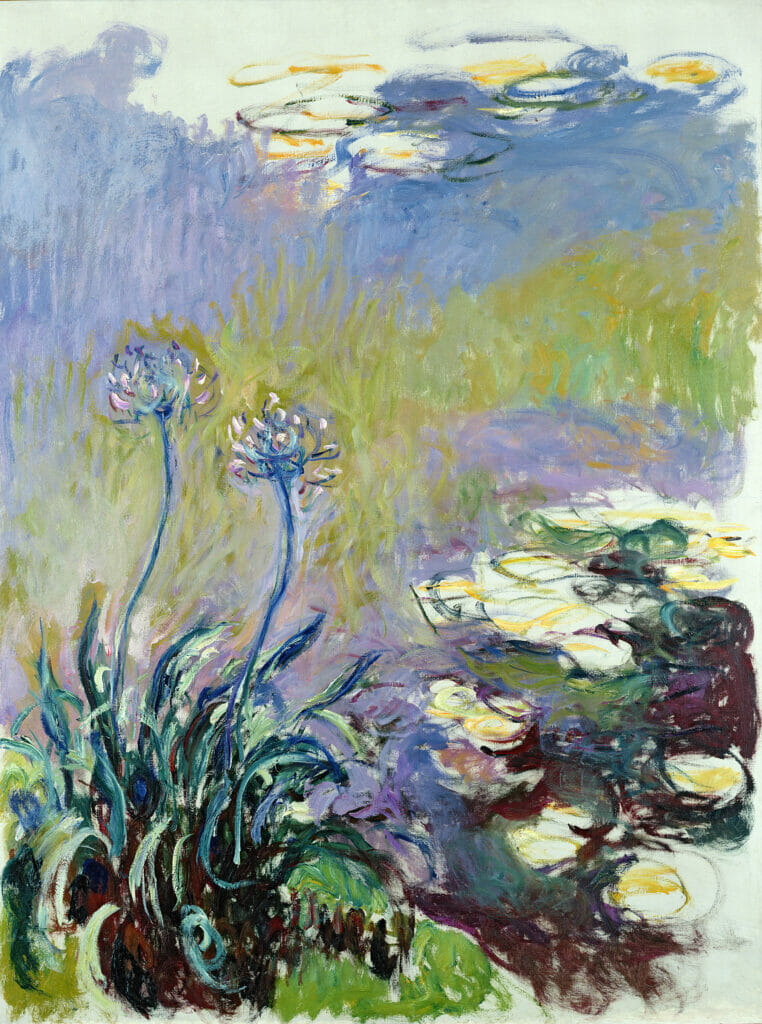

Hence, it is no wonder that Monet’s last thirty years were dedicated to his Water Lilies (Les Nymphéas). This cycle of 250 paintings enshrines his desire to illustrate the ever-so-slight changes of light on his beloved pond. When Monet settled down in Giverny, he designed his garden of Eden. The landscaping project consumed him as much as painting did. However, this investment in time and money was not in vain. Indeed, the gardens and the outdoors in general, were after all, the atelier of the impressionists. Only in the open air, could Monet observe that unutterable trembling of the light that he had pursued from Normandy to Venice, through Norway and Holland. In the later stage of Monet’s oeuvre, perspective was abandoned, and outlines gradually faded to prioritize light and colors.

Presented next to his late artwork, there is Mitchell’s work that seems at first glance to be unbounded and in total abstraction. However, her work tapped into the recollection of her memories, mingled with the experience of her surroundings. At night, she would paint the feelings evoked by the places she encountered during the day. This is the rich paradox that makes her work unique. Her abstract paintings sometimes seemed to form recomposed landscapes. In her fields or territories series, blocks of colors formed patterns that evoked cultivated lands. Indeed, she said:

My painting is abstract but it is also a landscape, without being an illustration

Joan Mitchell

Finally, some of the creations by Monet and Mitchell were designed as environments themselves. Indeed, these paintings are immersive. In the exhibition, their installations surround the viewers. This creates the possibility of wandering in artificial and poetic new worlds. Moreover, the dimensions of the canvas liberate the paintings from spatial constraints. Indeed, some of the exceptional series occupy entire walls. For instance, the triptych of the Agapanthus (1915-1926) measures a prodigious thirteen meters. Moreover, various polyptychs from the Great Valley series are presented together to form a complete visual panorama.

Oil on canvas, 93 x 74 cm

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Joan Micthell, The Great Valley, 1983 Oil on canvas, 260.4 x 200 cm

Foundation Louis Vuitton, Paris

© The Estate of Joan Mitchell

Photo : © Primae / Louis Bourjac

Two differing methods to transcribe the depth of feelings

Nature is not the ultimate subject for Monet or Mitchell. Indeed, it is more the contemplation of nature that triggered feelings, or sensations, that they wished to transcribe onto the canvas.

I do what I can to render what I feel when in front of nature, and that most of the time, to succeed in rendering what I feel, I totally forget the most elementary rules of painting, if there are any. In short, I will allow many mistakes in order to delineate my sensations.

Monet writes in a letter addressed to his friend Gustave Geffroy in 1912

In other words, Monet would compromise his technique to transfer his internal world to the canvas. Moreover, fellow artist John Singer Sargent, while visiting him in London around 1900, gave an account of his sometimes chaotic work procedure. Sargent watched Monet struggle, surrounded by 80 canvases, to find the right one depicting the light effect he was waiting for, and often he was not able to find it until the effect had already passed. Arguably, this feverish obsession and the audacity to break away from conventions made him ahead of his time and thus appeal to abstract impressionists.

For Mitchell, the use of particular colors was linked to feelings and emotions. Indeed, she shows affection for colors tied to her childhood. For instance, the color yellow in her paintings is not synonymous with the joy of marigolds. Instead, it cries out like the setting sun’s light on a winter’s day. Elsewhere, for Joan Mitchell, music and poetry are facilitators that helped her reach a state of metaphysical trance, one which allows pure creativity to blossom.

Oil on canvas, 200 × 180 cm

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Oil on canvas, 279,4 x 360,7 cm Private collection

© The Estate of Joan Mitchell

Photo : © Patrice Schmidt

Comparing the techniques and palettes of Monet and Mitchell

From the juxtaposition of the two artists, the viewers can detect a similar palette. Indeed, the blues, greens, and purples are dominant colors, meshed with hints of bright yellow and reds. However, the use and application of colors resonate differently in their paintings. For instance, in Monet’s Wisterias, the patches of pink and lilac pastels occupy most of the canvas. The colors seem to radiate from the subject, which conveys a velvety and chimerical idea of the flower itself. It is magical, and comforting and stimulates interior contemplation.

In comparison, Mitchell executes her paintings with highly saturated colors. Mitchell researched the effect that one color had on another, and what both of them did in terms of space and interaction. For instance, her use of cobalt blues is electrifying. Moreover, in her painting Edrita Fried (1981), her composition of complementary blue and yellow colors instigates a feeling of elevation of the soul.

The technique used is oil painting, both by Monet and Mitchell. In some places, the movements of their brush are similar, filamentous threads remind of calligraphic writings. However, the textures in their paintings differed widely. Monet’s brush strokes are short and supple, whereas Mitchell’s touch gives an impression of rapidity. Moreover, Mitchell created compact zones of colors alternating with empty spaces. She also added drips of paint. In one of her works, the superposed blocks of colors and the drippings surprisingly resembled layered graffiti tags on a crumbling wall.

Oil on canvas 100 x 300 cm

Musée Marmottan Monet courtesy from Wikimedia Commons

Oil on canvas, 279,4 × 680,7 cm

Paris, Centre Pompidou, in a depot in the Museum of Grenoble

© The Estate of Joan Mitchell

A dialogue to conciliate and deepen understanding

The comparison between Monet and Mitchell appeared when critics forged the notion of “Abstract Impressionism” in 1950. Elaine de Kooning would have coined the term to highlight the links between the last works of Monet and the abstract American paintings inspired by landscapes. This movement was attached to painters from the second generation of Abstract Expressionism to which Mitchell belonged. Moreover, Mitchell was among the few women recognized in this male-dominated art scene. Appearing in an interview in the documentary by Arte dedicated to Joan Mitchell, she said that others appreciated her only because being a woman, as she did not appear as a threat. She continued saying that Julius Carlebach told her “Oh, Joan if only you were French, male, and dead”.

These are three characteristics that define Monet, a phrase that echoes back to her comparison to him. Arguably, Mitchell’s work presented alone could have stirred less interest because it is less popular and disruptive than Monet’s. Indeed, Monet’s latest work approaching total formlessness is acknowledged as the origin of abstract art. Nevertheless, the juxtaposition opens a door into contemporary art for an audience less accustomed to appreciating abstract work. The dialogue is key because the purpose of the latter can seem at times, incomprehensible. Precisely, because representation disappears from the canvas. Even though, it seems to be looming over it. What remains is the nature of contemplation, or the attempt to crystalize what looking at beauty and wonder feels like.

Tag