Rediscovering the Goodhart Ducciesque Master | A Duccio-inspired Madonna and Child at the Hearth of Sienese Trecento Art

Material/Technique

Sir Charles Eastlake, together with his wife Elisabeth Rigby, travelled much to Italy at the time he directed the National Gallery. They were both enthusiastic about the purity of primitive Italian art, in particular Trecento paintings. Today, The Rise of Painting 1300-1350 at the National Gallery gathers their legacy through some of the most significant works that made Trecento Senese art exceptional. A remarkable example of this artistic sensibility is the Madonna and Child with the Annunciation and the Nativity by the Goodhart Ducciesque Master, which conveys the spirituality and intimate detail typical of early Sienese art.

The Goodhart Ducciesque Master case: a wooden panel like an illuminated page

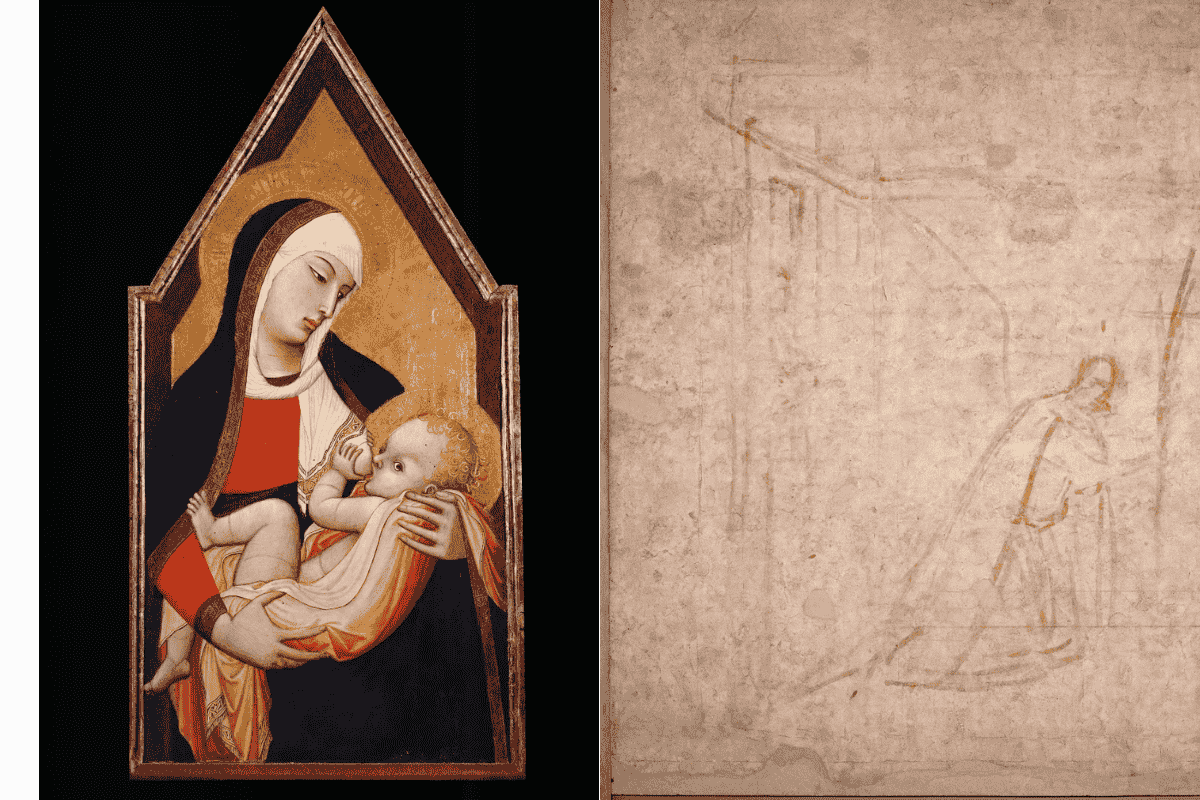

The trim panel with the Madonna and Child with the Annunciation and the Nativity (img 1) – by a close follower of Duccio di Buoninsegna, ca. 1310-15 – was created for private devotion. The dimensions, details, and organization suggest that the author knew the art of illumination. Initially a diptych, it misses the left wing, where maybe there was a Crucifixion. In the main image, the Child plays with the veil of the Virgin, and she looks straight at the devotee. A touch of humanity establishes a closer contact between the viewer and the intimate and delicate spirituality characteristic of early Sienese painters.

The Annunciation shows the shy and graceful attitude of Mary, whose cape falls in sinuous golden folds. The Nativity, although in the Byzantine scheme, presents enjoyable natural details. The ox and the donkey look after the Holy Infant with affection, and a variety of animals follow the shepherd.

Crazy for “Madonnas”: collecting the primitives in the nineteenth century

This small panel exemplifies the type of devotional artwork that charmed British collectors in the nineteenth century. Part of the broader “exodus of Madonnas,” such works were often removed from their original settings and dismembered (img 2-3). Hence, they were sold on a flourishing art market desirous of early Christian purity.

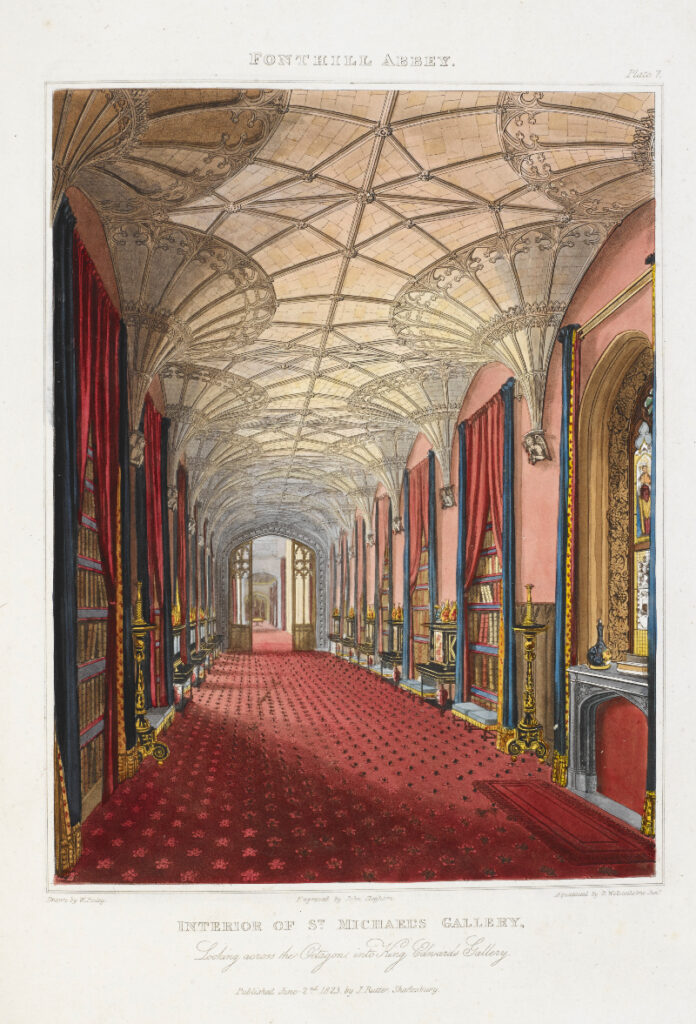

Charles Fairfax Murray, who lived in Florence and travelled to Siena, played a key role in sourcing and interpreting the artworks for collectors and institutions. Influenced by Ruskinian ideals, Murray saw in these Sienese images a spiritual value lost in modernity. They found eager homes in Britain, from aristocratic collections to eccentric settings like William Beckford‘s neo-gothic folly, Fonthill Abbey, where medieval art intertwines with a vision of romantic, sublime beauty (img 4-5). These Madonnas were more than ornaments. Indeed, they became cultural references, embodying a nostalgic craving for an imagined, sacred medieval past filtered through Victorian eyes.

A specimen perfect for a clergyman

In 1835, William Young Ottley purchased The Madonna and Child, along with many other early Italian paintings, including the panels from Ugolino di Nerio’s Santa Croce Altarpiece (image 6). In 1836, the panel passed to his brother Warner. Next, the 8th Earl of Northesk exhibited it in his Scottish castle from 1847 to 1890 (Reverend Barnes). Then Thomas Sutton owned it, and in 1920, the MET bought it from Taddeo di Bartolo.

In the 1950s, the panel was attributed to a follower of Duccio. It was the perfect work to include in a collection. It was a small specimen of early Sienese art, not expensive and representative of primitives. The fact that a Reverend owned it exemplifies the role that this and many other similar panels played in clergymen’s collections. Without a doubt, they fitted the adorned ambience of an ecclesiastic space with the aesthetics of pure morality and spirituality.

The Sienese reunited and their legacy

The exhibition at the National Gallery highlights the importance of reuniting artworks that have been scattered around the world. Once part of devotional spaces, these paintings now dialogue again in a setting that enhances their original function and value. They shaped the Sienese artistic and cultural scene in the Trecento and continued to have an impact on the modern world.

Their charm transcended the sacred: in Victorian Britain, such works sparked visual revolutions. The aesthetic ideals of early Italian painting inspired the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with passion, reviving their clarity, symbolism, and intense emotion. These Madonnas and saints shaped interior design, furniture, and even fashion, becoming icons of a broader cultural yearning for purity and craftsmanship. Today, bringing them together demonstrates that the artistic flourishing generated this legacy, that of the enduring impact these primitives have had on our perception and contemplation of Medieval art.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic