The Nightmare | In the meanderings of the subconscious of Füssli

Artist

Year

Country

Material/Technique

Dimensions

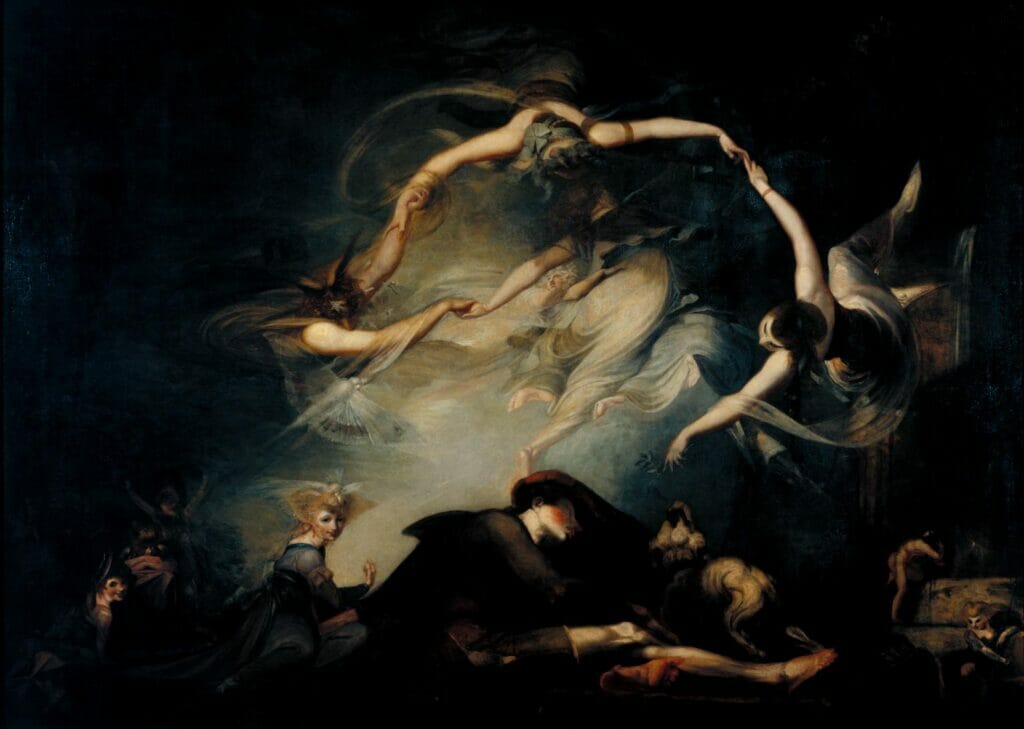

One of the paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy of London in 1782 caused something of a stir at the time, the frisson of shock partly because of its veiledly erotic atmospheres and partly because it brought to the stage the most frightening part of the unconscious in ways as crude as never before. This was The Nightmare, the most famous painting by the devil painter, as the Swiss-English painter Johann Heinrich Füssli used to call himself. The work, painted when he was 36, was an immediate success and was made into several replicas. It still captures the modern observer today because of the universal phenomenon it showcases: nightmares.

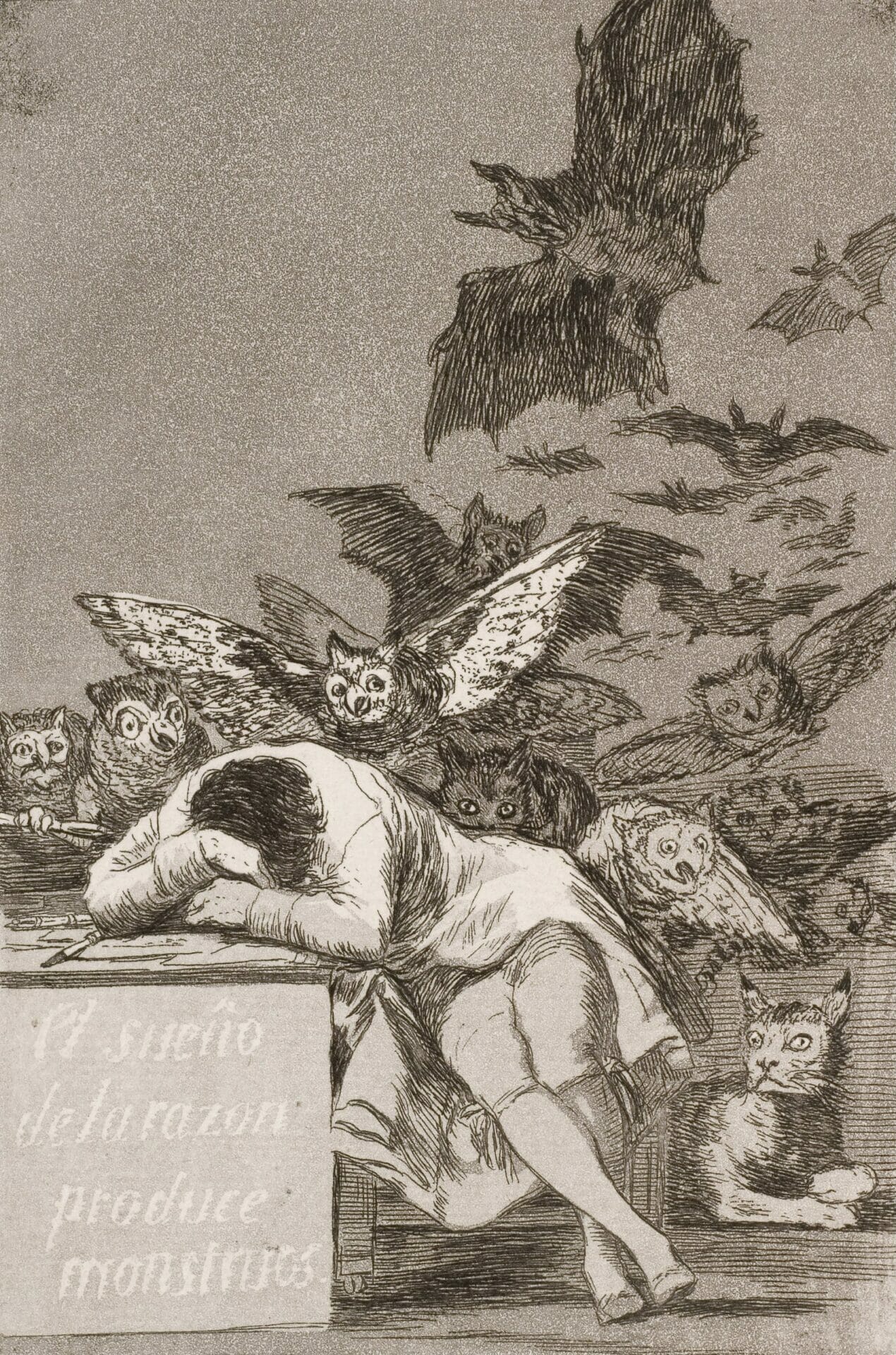

In aphorism number 231 of the collection written by Füssli between 1788 and 1818, he states: “One of the least explored regions of art is dreams.” In The Nightmare, the artist portrays a nightmare and the dark part of the unconscious that expresses itself through it for the first time in art history. For the first time, he portrayed together reality as such and its unconscious, obfuscated version.

Between reality and dreamlike imagery

The painting depicts a woman inside a room. She lies on a bed in the grip of hypnagogic illusions, or daydreaming nightmares. Her unconscious body, arms and head are dangling on the floor. A fiercely grinning demon sits on her chest. Its pointed ears and hump emerge from the dark background, like in a Gothic gargoyle. It is the depiction of an “incubus” that has just sucked the life out of his victim. With his terrifying gaze, he looks at the viewer as if he were his next victim. To the demon’s left is the head of a white horse with pupil-less, hallucinated eyes. An erotic symbol belonging to the imagery of Scandinavian nightmare legends.

The only illuminated parts are the girl’s body and the white robe from the veiled fabric enveloping it, some furnishings resting on the bedside table, and the blanket yellow and orange, all of which belong to reality. The rest of the furniture and the monsters are dimly lit and barely emerge from the darkness and representing the girl’s unconscious. The illuminated physical space in the foreground fades into the space of the girl’s unconscious and dreamlike imagination shrouded in darkness.

The Nightmare (1781), Johann Heinrich Füssli, Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Detroit Institute of Arts.

The Nightmare was only the beginning of a series of other works on the same theme. Later in A Nightmare leaves the bed of two sleeping girls (1793), instead, he portrayed the awakening from the dream. Then other scabrous dreams. In 1793, The Shepherd’s Dream from Milton‘s Paradise Lost. Between 1796-1804 The Dream of Eve and, in 1789 Richard III and the Wraiths from Shakespeare’s play of the same name.

Incubus, the demon of the night

Füssli drew on 16th- and 17th-century folk literature, especially English, about nightmares, in the making of painting. The word “Nightmare” itself is formed from the union of “night” and “mare”. “Mare” in English means “female horse,” an animal that appears in the painting, but also denotes a small demon that in Scandinavian mythology torments sleepers. As it appears in 18th-century dictionaries, the most common symptoms of nightmares are numbness of the body and a sense of heaviness in the chest, as if someone were sitting on it. In fact, the Latin translation of “nightmare” is “incubus” which comes from “incubare” or “to lie on top of”.

According to ancient mythological beliefs, the incubus was a demonic being that oppressed people in their sleep and even conjoined carnally with them thus causing nightmares or hypnagogic illusions. These are hallucinatory daydream visions that occur in the REM phase during which the victim remains paralyzed and cannot wake up completely, thus becoming trapped in the nightmare. These monsters were called by different names in different folk legends. For the Romans, they were fauns or rural deities, in the Middle Ages a kind of proto-vampires. In Norse mythology they were Mahr, and in Italy, they were a witch called “Pantafica.”

Italy, an inspiration

Füssli as a good connoisseur of figurative art, in addition to letters, felt the influence of various works for the creation of The Nightmare. He was especially inspired by Italian works he became aware of during his stay in various parts of Italy, including Rome, Naples, and Florence. It is said that he spent entire weeks studying the details of Michelangelo‘s Sistine Chapel, of which he was a great admirer. Not surprisingly, critic Nicholas Powell identifies the source for the maiden’s pose in the Sleeping Ariadne in the Vatican and the source for the horse in the Horse Tamers on the Quirinal in Rome.

Other pictorial sources attributed by critics are the Dream of Hecuba, Giulia Romano‘s decoration in Mantua for the Palazzo Te, the fitting found at Pompeii and Herculaneum for the furnishings of the bed and the table, and the classical Sileni types for the “incubus”. While Chappel, on the other hand, identifies more specific similarities with the Bacchanalian scene on the marble sarcophagus of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale of Naples. He found parallelisms between the sleeping Maaenad and the woman in The Nightmare like the position with the arms backwards, the robe wrapping around the women’s curves, and the cut of the curtain.

A story of love and eroticism

Art critic Janson, in 1963, interprets the painting in a strongly erotic and autobiographical key. In 1799 Füssli fell in love with Anna Landolt von Rech, the granddaughter of his friend the physiognomist Lavater. A love that was not consummated because of the opposition of her father, who made her marry another man. The artist was devastated and fell into deep despair. Janson argues that the girl in the painting is a projection of Anna and that the nightmare is Füssli himself. Other erotic symbols would be the horse, the fiery red of the curtain, and the transparency of the woman’s dress.

In the 1753 Essay on the Incubus or Nightmare (and in several other sources on the subject of that time), the main victims of nightmares include precisely the victims of the evils of love. Moreover, on the back of The Nightmare delivered to the Detroit Insitute of Art there was hidden an unfinished portrait of a seductive young woman who resembles the artist’s beloved, a fact that would further validate such an interpretive key.

Füssli, the evil painter and the great precursor

Füssli used to refer to himself as the “painter in the service of the devil”. He favored depicting monstrous figures such as mischievous witches, galvanized devils, and satanaxes. All these subjects surrounded the painter’s home, according his painter friend Benjamin Robert Haydon. Due to his rare and innovative expressive and imaginative power, also given by the original coexistence of neoclassical and romantic elements in his works he was an inspiration for several contemporary and subsequent artistic currents.

For example, his artistic work coincides with the publication dates of the most important works of Gothic literature such as Horace Walpole‘s The Castle of Otranto (1764), Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus (1818) and John William Polidori‘s The Vampyre (1818). The Nightmare established a defining leitmotiv in the Gothic novel since they have as a common device the nightmare. Mary Shelley herself, as critic Sophia Andres states, took inspiration from it for the description of Elizabeth Lavenza‘s death, the fiancée of Victor, the creator of Frankenstein.

‘She was there, lifeless and inanimate, thrown across the bed, her head hanging down, and her pale and distorted features half covered by her hair.’

Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus, 1818.

The Nightmare in pop culture

The dreamlike and hallucinatory images Füssli enacted would become a source of inspiration for the Symbolists. While for visionary episodes and atmospheres rich in pathos, the artist would be a forerunner of Expressionism and Surrealism. But The Nightmare, thanks to the universality of the theme it enacts still appeals to the modern viewer. In pop culture, the impact of it can be seen in various areas. In Wes Craven‘s 1984 movie, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Freddy Krueger is a kind of “incubus” or boogeyman. He kills the children of the men who burned him alive while they sleep.

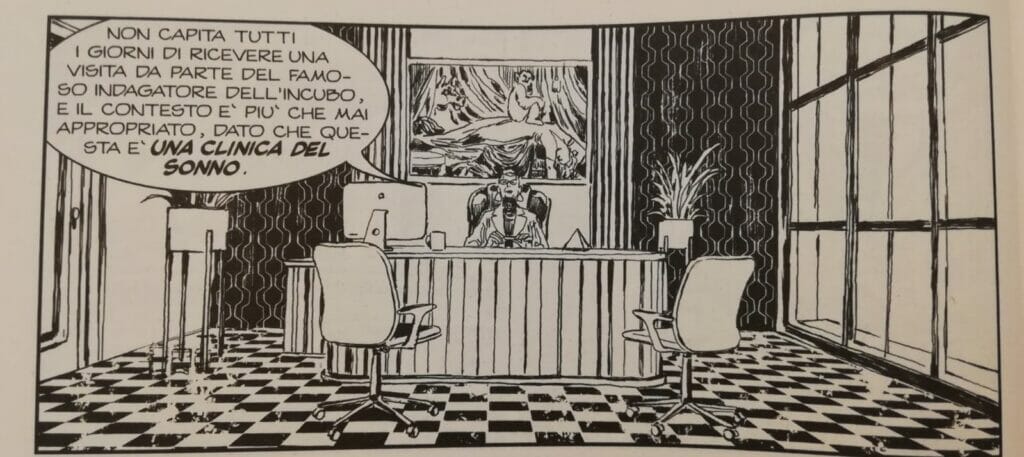

Similarly, Füssli’s painting also influenced the construction of a historical enemy of Dylan Dog (“the nightmare investigator”), namely Mana Cerace, one of the monsters in the comic, a boogeyman who also kills in his sleep. An explicit reference to Freddie Kruger. The Nightmare is then the absolute protagonist of issue 434 of the regular series Non con fragore…, written by Claudio Lanzoni, Barbara Baraldi and drawn by Sergio Gerasi. In this comic Dylan carries out his investigations inside a sleep clinic. During the meeting with Dr. Heche, Füssli’s The Nightmare stands out in his office (plate 18) since the patient of the clinic Dylan is investigating suffers from hypnagogic paralysis. Dr. Heche claims that perhaps Füssli himself also suffered from hypnagogic illusions and that he also saw:

(…) black, threatening shadows perceived by the subject as hostile presences from which he feels physically threatened.

Non con fragore…, 2022.

Non con fragore…, 2022, © Sergio Bonelli Editore SpA. Dylan Dog è un personaggio creato da Tiziano Sclavi.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic