Fahrenheit 451 transcends the boundaries of science fiction

Author

Year

Format

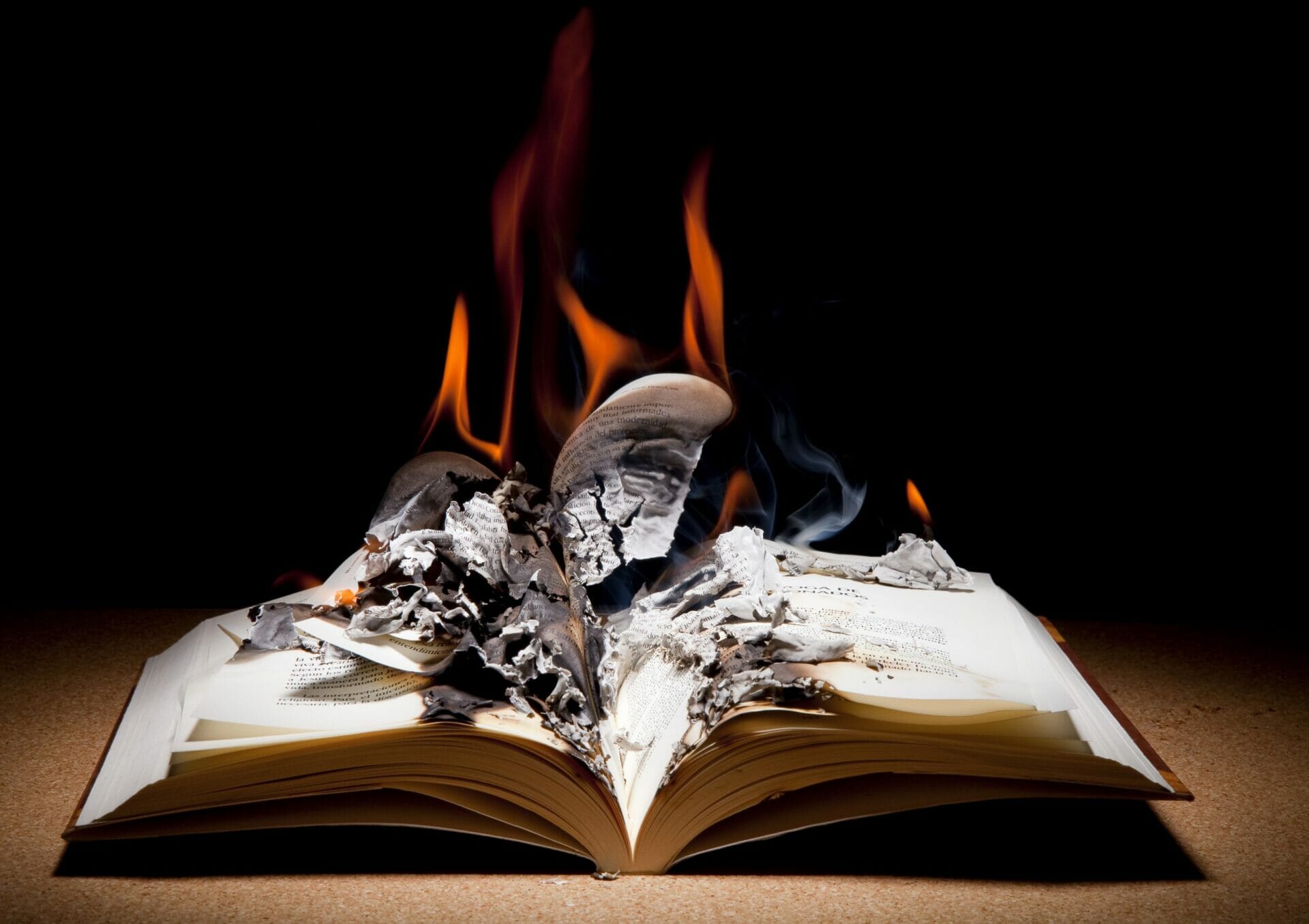

Fahrenheit 451 is the temperature at which paper burns and the number engraved on the hat of the firemen who have the task, in the dystopian world imagined by Bradbury, to burn every existing book. In an unspecified post-1960s uchronia, a totalitarian society has forbidden the possession and consumption of any literary product, on pain of the house seizure and a prison sentence. Guy Montag, the protagonist of the novel, carries out his task – he’s a fireman – with precision and dedication until he meets two women. The first one is an old woman who chooses to burn in her house with her books. The second one, Clarissa, is a mysterious girl who has the apotropaic task of breaking Guy’s imposed blindness.

A critique to contemporary society

Bradbury’s novel has transcended the boundaries of science fiction literature to become a true classic of popular literature, and like every classic, it is still relevant. The story of a society where iconography and simplification have replaced verbal language resonates with some aspects of the contemporary world.

Like two other great works of science fiction authors, Huxley’s Brave New World and Orwell’s 1984, Fahrenheit’s world is a world where control passes through information management. If the influence is clear, for a 1953 book, of recent historical events (the Nazi book burning, the Stalinist purges, the politics of McCarthyism), it is likewise undeniable that Bradbury focuses, from the sensationalism of dramatic events to the prevailing presence of the mass media in our homes, on some crucial points of our daily life.

Memory and imagination

The novel is the elaboration of a story that initially came out in the newborn Playboy magazine since no one else wanted to take the risk of publishing such a politically hot work. Later, François Truffaut made a film adaptation of it in 1966, which helped make some scenes or dialogues memorable. In the 2000s, Michael Moore took the novel’s title up as a tagline for his two Fahrenheit (9/11 and 11/9).

The group that Montag meets at the end – or the beginning? – of his journey, a society of men-books (who have learned pages and pages of literature by heart so as not to see it vanish) is a beautiful image of the link between memory and imagination and the importance of the human element in the transmission and narration of culture.