Blade Runner | The Future on a Razor's Edge

Year

Runtime

Director

Cinematographer

Music by

Format

Genre

Few movies deserve the title of “visionary” as much as Blade Runner. Directed by Ridley Scott (hot on the heels of the success of 1979’s Alien), the movie depicts a dystopian future of rare vividness. And its implications, both timeless and contemporary, over the years made it a must-see classic.

The year 2019. The Earth is overpopulated and plagued by all kinds of pollution. Those who can flee to other planets, the so-called “off-world colonies”, in search of a better life. To meet the colonies’ need for slave labor, the Tyrell Corporation, the world’s most powerful tech company, provides “Replicants”: biomechanical, sentient androids that are virtually equal to humans – even when it comes to emotions. As a safety mechanism (for humans, that is) replicants are equipped with artificial memories and a lifespan of only four years.

Four of them, led by the Luciferian Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), mutiny and flee to Los Angeles, in an attempt to infiltrate Tyrell’s headquarters. Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a retired “Blade Runner” – the special unit tasked with hunting down the insurgent Replicants – is then forcibly called back into service. His task soon proves more difficult than expected. And an encounter with the melancholic prototype Rachael (Sean Young) will make him question his own humanity in every way.

Future is the ultimate critic

Now a cult classic, Blade Runner was poorly received by audiences and critics alike at the time of its release. For instance, film critic Pauline Kael called it a “suspenseless thriller” that showed more interest in visuals than storytelling.

One reason for the flop was the changes the producers made to try to appeal to more mainstream tastes. Most notably, the recording of voice-overs for Deckard (introduced to recap the most elusive plot points) and a far too happy ending which did cause more than one inconsistency.

Another is bad timing. Audiences were fed up with the post-apocalyptic scenarios of the 1970s and were not yet ready to look at a future as pessimistic and yet prophetic as that typical of the 1990s. In addition, Steven Spielberg released E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial in 1982. The movie offered a far more reassuring idea of science fiction – first pioneered by Star Wars (1977) – and would go on to break box office records worldwide despite its daring competition. John Carpenter‘s The Thing also struggled financially because of this.

But, as with any cult movie worthy of its status, a slow and visceral reappraisal followed. In 1991, Scott had the opportunity to work on a first director’s cut to restore his vision of Blade Runner. And finally, in 2007, after 25 years of influence on the collective imagination, a final cut of the movie arrived. Scott reportedly framed Kael’s review on his office wall, where it remains to this day. After all, the future is the ultimate critic.

Back to the future

Loosely based on the novel But Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, the screenplay by Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples is a synthesis of thoughtful and spectacular cinema. The existential and ecological concerns are the fruit of Fancher’s early drafts. From Peoples’ production-mandated rewrites come the high-concept plot and genre mixing.

The seasoned bounty hunter’s execution of his targets in a series of duels, one by one, are downright Western elements dressed up for the future, and Peoples would go on to write the screenplay for Clint Eastwood‘s 1992 breakthrough as a director, Unforgiven. The introspective tone, the general melancholy, and the tropes of the private eye and the dark lady, along with its problematic aspects, trace the sci-fi plot back to the noir genre. The result is a neo-noir flick in the most futuristic sense of the word. And Scott and cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth played this core to the hilt.

In a constant play of light and shadow, smoke and primary colors, the film carefully crafts an almost expressionistic look. The connection between such a style and noir is far from accidental. Many stylistic elements of German Expressionism had migrated to the genre as anti-Nazi directors moved to Hollywood during the Reich, most notably Fritz Lang. And indeed, his expressionist sci-fi classic Metropolis (1927) is one of the main visual references for the movie. In this sense, Blade Runner is a kind of homecoming or reborrowing.

Vangelis‘ retro-futuristic score completes the picture, blending blues and electronic music, and incorporating Japanese and Greek melodies into a quintessential Hollywood soundtrack.

The end result is a tech-noir outside of time and space. And thus capable of reaching universal depths and truths. That’s the paradoxical beauty of the postmodern. “Copies of a copy” become “myths of a myth”. The patchwork of the most disparate sources (if done right) strips them of their contingencies until nothing’s left but distilled wonder. Until all that remains is pure epic:

When the choice of the tried and true is limited, the result is a trite or mass-produced film, or simply kitsch. But when the tried and true repertoire is used wholesale, the result is an architecture like Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. There is a sense of dizziness, a stroke of brilliance. […] When all the archtypes burst in shamelessly, we reach Homeric depths. Two cliches make us laugh. A hundred cliches move us. […] Something has spoken in place of the director. If nothing else, it is a phenomenon worthy of awe.

“Casablanca, or, the Cliches Are Having a Ball” by Umberto Eco

Visions from the metropolis

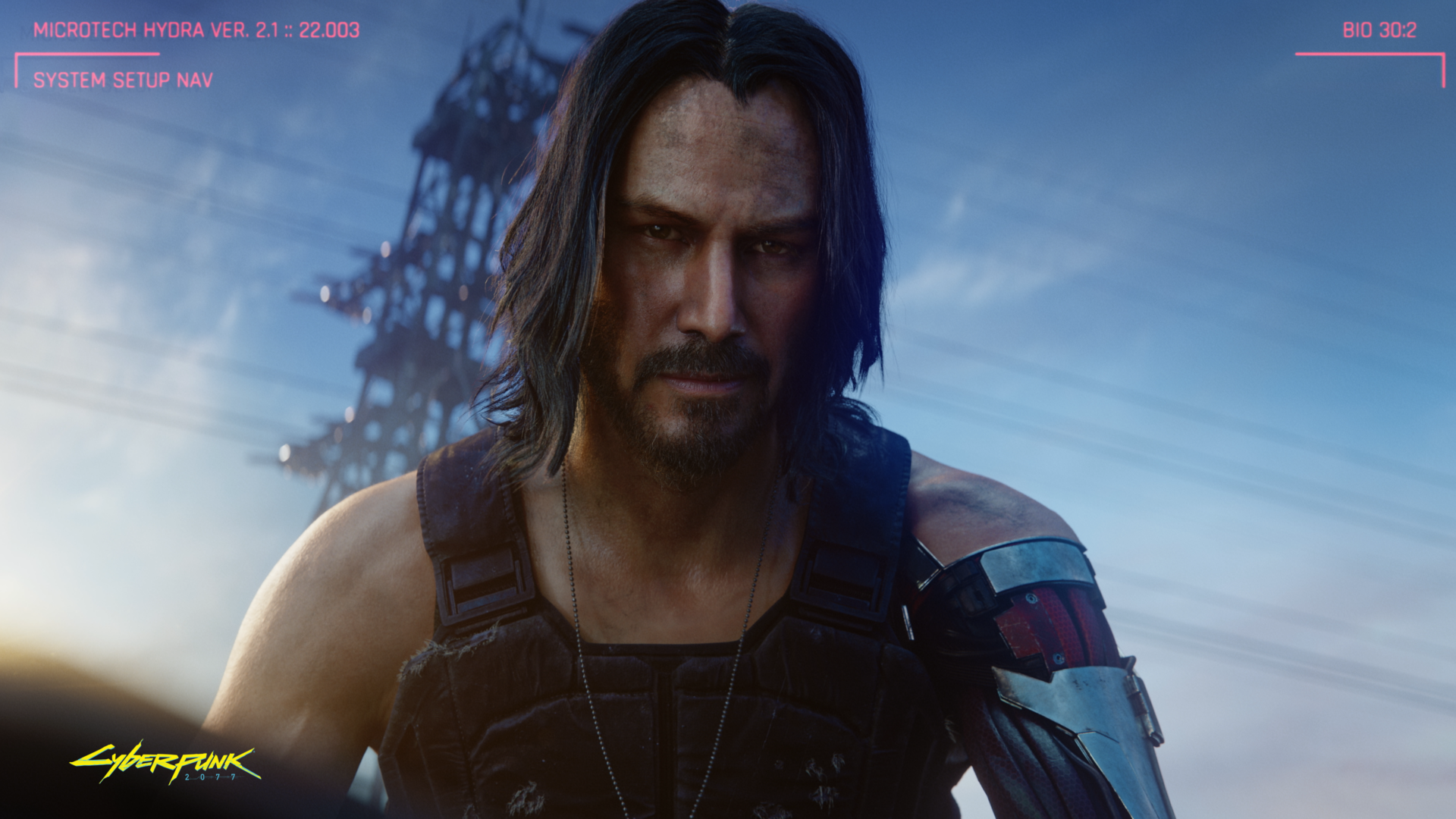

With its peculiar vision, Blade Runner provides a perfect objective correlative for modernity, for what was (and is) an increasingly brave new world. As a result, this vision became a highly influential trend in the decades following its breakthrough. Blade Runner set itself up as a benchmark – if not a manifesto – for a unique subgenre, the most appropriate for depicting future civilization and its discontents: cyberpunk.

Katsuhiro Ōtomo‘s Akira series (1982-1990), Masamune Shirow‘s Ghost in the Shell franchise (1988-2020), Lana & Lilly Wachowski‘s The Matrix saga (1999-2003), even David Fincher‘s Seven (1995) and the Batman movies directed by Tim Burton and Joel Schumacher all owe much of their dark mood, look and feel to Blade Runner. Scott himself returned to it in several of his subsequent works. From the neon-lit Tokyo of the action flick Black Rain (1989) to the violently chaotic Florence of Hannibal (2001), the tide of Blade Runner has yet to recede.

The unmistakable look of cyberpunk is evident in the bizarre costumes, in the over-the-top makeup, and most importantly, in the monumental production design based on the sketches of concept artist Syd Mead. A design that glamorizes junk in yet another mix of ancient and modern. A design that juxtaposes dark and cluttered apartments with the overcrowded metropolis on a perpetually rainy night due to pollution, lit only by the neon lights of its oversized neo-Gothic skyscrapers.

In such an alienating environment, anything but silence and solitude seems unrealistic. A cocktail of claustrophobia and agoraphobia (which also characterized Scott’s Alien) emerges. The struggle for survival is all that’s left, or so it seems.

Everybody wants to ruin the world

Pauline Kael blamed the movie for this desolation:

Here we are – only forty years from now – in a horrible electronic slum, and “Blade Runner” never asks, “How did this happen?” The picture treats this grimy, retrograde future as a given – a foregone conclusion, which we’re not meant to question. The presumption is that man is now fully realized as a spoiler of the earth. The sci-fi movies of the past were often utopian or cautionary; this film seems indifferent, blasé, and maybe, like some of the people in the audience, a little pleased by this view of a medieval future – satisfied in a slightly vengeful way. […] “Blade Runner” doesn’t engage you directly; it forces passivity on you. […] The people we’re watching are so remote from us they might be shadows of people who aren’t there.

“Baby, the Rain Must Fall” by Pauline Kael – The New Yorker

But that’s the point. In most dystopian stories (including Blade Runner 2049), the main characters want to save or rule the world, or at least deal with its state. In Blade Runner, the apocalypse is assumed, somewhat absentmindedly. It is a fact like any other, a nuisance that everyone can live with, like the incessant rain. Of the many prophecies of cyberpunk, this is the most frightening, and also the closest to (self-)fulfillment.

Blade Runner is no longer science fiction. It’s a contemporary thriller.

“Are we living in a Blade Runner world?” by David Barnett – BBC

The events of the plot have no effect on their surroundings. The viewer can almost sense that they are just some of the many affairs that take place in the metropolis. Yet Blade Runner‘s evocative power grows stronger the bleaker the picture becomes. The movie thrives not only in spite of this vanity but because of it. It refuses any form of naïveté. But thanks to such a contrast, it leaves room for the most honest kind of hope.

The Replicant party

When Replicants are advanced enough to develop emotions, and their human creators prove to be nothing more than cold calculators, the result is inevitable: rebellion, however desperate or violent. A political undercurrent creeps in. After all, the Replicants are slaves pitted against their creators (and their arena is a world from which all able-bodied white people seem to have long since fled). The more hopeless their rebellion becomes, the more titanic the tones it takes on, in full John Milton‘s Paradise Lost fashion.

To describe the Replicant condition, Roy Batty paraphrases a passage from the poem America: A Prophecy by William Blake:

Fiery the angels fell;

deep thunder rolled around their shores;

burning with the fires of Orc.

Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer)

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake famously said of Paradise Lost, that John Milton was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it”. The same is true of Blade Runner. What at first appears to be a malfunction in the script – the fact that the viewer sympathizes more with the villains than with the hero – becomes its trump card.

By taking the side of the replicants while telling the story from the human point of view, Blade Runner maximizes ambiguity. And it achieves depth as a result, in the notion that doubts and questions are much more important to stories than clear-cut positions and closed answers.

Razor’s edge runners

The question of who is truly (and actually) human arises. Replicants can have artificial memories. And thus artificial identities, since past experiences and lived lives are fundamental to the sense of self. But their desires are more human than human, if not too human.

It soon becomes clear that surviving is not enough. One must also live a meaningful life. But if these attempts at meaning prove fragile, perhaps the true quest – for both humans and Replicants – is to find some peace of mind with which to reconcile oneself. The movie’s most famous monologue delivered again by the machine man Roy Batty says it all:

I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe… […] All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain… Time to die.

“Tears in the rain” monologue, written by Hauer himself, who also had the idea to quote Blake.

In a way, it is close to the Japanese concept of Mono No Aware: the feeling of detached awareness of the transience of all things, at once melancholic and serene. And it is a possible answer to the existential tension that Blade Runner manifests from its very title. “Running the blade” implies living on a razor’s edge, for brevity and vanity, under metropolitan rain.

Batty’s monologue is delivered to Rick Deckard, the bounty hunter who doesn’t fully share the cruelty of humans. And thus, of course, to the viewer. The final quote from another cult classic comes to mind. Despite the radical differences with Blade Runner, it’s still a principle for science fiction as a whole:

The unknown future rolls toward us. I face it for the first time with a sense of hope, because if a machine, a Terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can too.

From James Cameron‘s Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991)

Tag