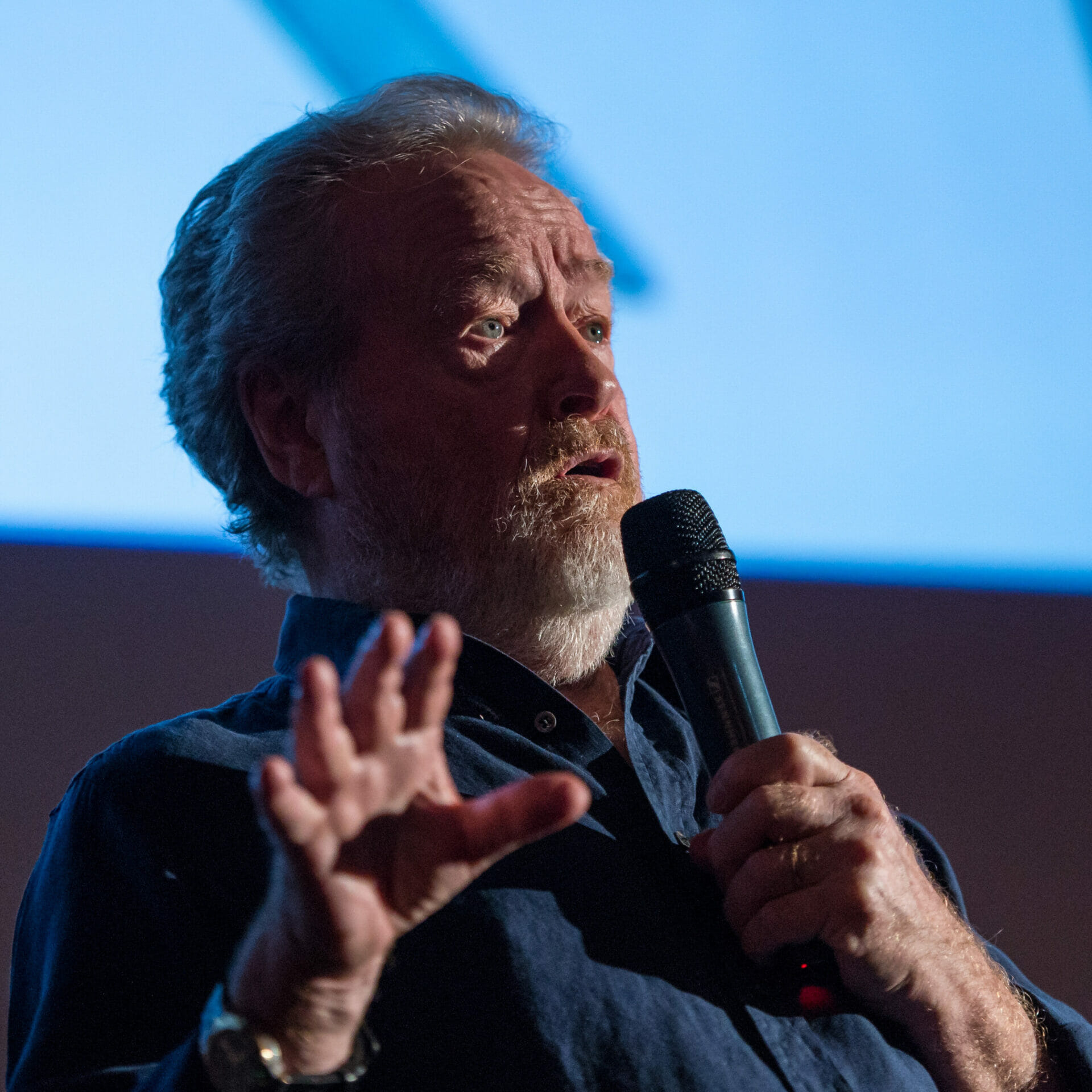

Ridley Scott 85 | The Last Film Craftsman

Ridley Scott is one of the last, true film craftsmen of the last 40 years. Although his career has spanned the most disparate genres (sci-fi, thriller, historical drama, road movie, and even fantasy) without ever writing a screenplay, his movies have always retained an instantly recognizable look and, at their best, provided some of the most intense moments in contemporary Hollywood cinema.

On the occasion of his 85th birthday, we celebrate this filmmaker and his career.

Who influenced him

Scott’s visual prowess can be traced to his years of training as a director of commercials, where he learned the importance of making compelling moving images, the discipline necessary to never let style supersede substance, and the necessity of building and assembling teams of artists just as visionary as himself.

The director’s most recurring references are the works of Stanley Kubrick, Fritz Lang, and Akira Kurosawa, all three of them competent craftsmen and expert storytellers at the same time.

Starting from his debut The Duellists (1977), Scott made the expressive use of light one of his trademarks. The work of Kubrick comes to mind, especially Barry Lyndon (1975), but with a twist. Where Kubrick relied on the interplay of natural and artificial light, Scott always instructed his cinematographers to come up with downright artificial solutions, sometimes at the expense of continuity logic, but never of suspension of disbelief.

Set during the years of Napoleon’s rise and fall, The Duellists tells the story of a French lieutenant bound to a never-ending duel with a fellow war-mongering officer. It soon becomes apparent that either of the two could die and it wouldn’t matter, for in the eyes of the war – and of history as a whole – their lives are interchangeable and expendable. As such, neither of the two receives any special treatment from the director’s lights and camera. Scott’s use of strongly backlit chiaroscuro shots would be the perfect visual fit for this metaphor for the meaninglessness of war, and it would become a tell-tale sign of his style.

Scott would take such an approach to cinematography to its extreme consequences with Legend (1985), one of his most stylistically refined movies. A straightforward fairy tale about the fight between good and evil – and light and darkness – in the hands of Scott it becomes a monument to counter-light cinematography, to the point where (against any spatial logic) the vast majority of the shots are backlit. While mannered at times, the choice is far from gratuitous. By highlighting the linings of the elements of the frame, counter-light cinematography compliments the depth of field, creating an alluring effect, a sense of wonder, on the viewer, who – regardless of their best judgment telling otherwise – can’t but be drawn into the magical world of the movie.

The Tête à Tête time in a Marriage A-la-Mode

Scott’s time to shine comes when he deals with the art of building the world of a story. Following the example of Lang, his world-building is not just a matter of envisioning – Scott storyboards all his films himself – but also of teamworking, of having all the artists involved in a high-budget production (with their disparate backgrounds) on the same page, with the aim of achieving a single, unforgettable vision. It’s this very skill that allowed him to kickstart not one, but two franchises, one for each of his two main hits: Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982).

Alien would not have haunted the nightmares of generations were it not for Scott’s ability to put Hans Ruedi Giger‘s neo-surrealist art into action. The biomechanical design of the alien’s anatomy and its world perfectly answered the director’s task of enacting the script’s Eros-Thanatos innuendos, of making them crawl under the viewer’s skin and then into the collective memory.

Blade Runner (which borrows several shots from Lang’s 1927 Metropolis) would not have set a benchmark, if not a manifesto, for the cyberpunk subgenre, if it weren’t for the artwork of the many artists who worked on the project, one above all, Syd Mead on production design. Glamorized junk, dark and cluttered apartments, an overcrowded metropolis on a perpetual rainy night, and lit only by the neon lights of its neo-gothic skyscrapers: all of this provided Scott with a perfect objective correlative for this story of alienation, loneliness, and the fight for survival in a desperate search for some hope.

Scott would return to this vision of an increasingly brave new world, in several of his subsequent works. From the neon-lit Tokyo of the action flick Black Rain (1989) to the violently chaotic Florence of Hannibal (2001), the tide of Blade Runner has yet to recede. And all of this is thanks to the virtues of style.

“All is fair in love and war”, goes the adage. The same is true about its representation, and the stylistic tactics to use in its depiction. In this sense, Scott learned from Kurosawa the grandeur, mastery, and freedom necessary to execute his epic set-pieces, whether they be spectacular battles – as in Gladiator (2000), Black Hawk Down (2001), and Kingdom of Heaven (2005) – or enterprises small as one-on-one combat. Desaturated colors, frenzy editing, strategic injections of slow-motion shots: these are but some of the many visual devices Scott employed for his epics, which would go on to set yet another standard for how to shoot a battle scene in the 2000s.

When it comes to duels, the grand finale of Blade Runner or Gladiator may come to mind (not to mention The Duellists), but his recent The Last Duel (2021) also ought to be remembered. The movie is also inspired by Kurosawa in its narrative deconstruction since it shares with Rashomon (1950) the idea of exposing the same event from the contrasting points of view of the characters involved, so as to show the all-too-human failure in the face of their grand ideals of Truth and Justice (and how women are those who suffer the most because of such fallacies).

Ultimately though, the movie proves that Scott’s calling for enacting duels is something that runs deep in his body of work, a trope to which he continuously returns. Not because it’s his comfort zone, but because he strives for perfection in his field of maximum expertise, as every good artisan does.

Throne of Blood | Translating Shakespeare into Film

What he created

Scott has the rare ability to translate the words of great scriptwriters into intense images. Like the most skilled of performers, Scott manages to reach the innermost core of the pages before him, and then unveil and display their essence, with spontaneity rather than intellectualism, for everyone to see.

Thelma & Louise is a case in point. Callie Khouri’s Academy-Award Winning screenplay – a manifesto of third-wave feminism – does not lose an ounce of its force in the hands of Scott. Instead, in its constant reversal of the male gaze and savvy use of American badlands, this road movie turned chase-thriller ends up being an epic search for freedom and identity in the heart of the wilderness.

And the titular Thelma and Louise are not alone in the director’s pantheon of charismatic female leads. From Alien‘s Ellen Ripley to The Last Duel‘s Marguerite de Carrouges, over the years, Scott has shown a sense for heroines that in Hollywood (when it comes to male directors) has rarely been matched.

Whom he has influenced

Recently, a director who has proved to be at the level of Scott when it comes to female protagonists and substance-through style is the Canadian Denis Villeneuve. Even before explicitly following in Scott’s footsteps by directing Blade Runner 2049, Villeneuve (after spending the first part of his career in the arthouse realm) was already a craftsman of high-quality genre movies. With his eye for well-rounded characters and his attention to performances and images that can work more than well on the silver screen, he might as well apply for the position of Scott’s heir.

Another director who has more than one thing in common with Scott is David Fincher (who made his debut in Hollywood in 1992 by directing a sequel of one of Scott’s biggest hits, Alien³, which partly aims at the same atmosphere of the original). Both of them cut their teeth by shooting commercials (and, in Fincher’s case, video clips as well). Neither of them writes scripts for their movies, but both know how to make the most of them by directing. The look of Fincher’s movies sometimes recalls Scott’s works: for instance, the rainy, alienating metropolis of Se7en (1995) traces back to the dystopian L.A. of Blade Runner. And, at its best, Fincher’s body of work, like Scott’s, goes beyond packing visually refined pictures: it creates meaningful images for worldwide audiences to see.

In 2016, The Hollywood Reporter gathered together some of the most prominent directors in the award season of the year for one of its customary roundtables of nominated artists. Along with Scott (who at the time was campaigning for The Martian), Quentin Tarantino, Alejandro G. Iñárritu, Danny Boyle, David O. Russell, and Tom Hooper were present.

The esteem that all these filmmakers had for Scott soon became apparent. What captivated them – other than his personal charisma – was Scott’s extreme confidence in his craft, and in the endurance that allows him to put out at least one new movie every year despite his now 85 years of age. The latter is a consequence of the former.

Not all of Scott’s works are on par with his most well-known ones. But Ridley Scott’s images do what they say and say what they mean. And that’s the most significant accomplishment an artist or craftsman can ever hope for.

Astonished?

Happy 85th birthday, Ridley Scott!