The Karamazovian day of Diego Armando Maradona

Discipline

Event

Date

Country

Length

Winner-Podium

Other protagonists

Year

By

Why? Precisely because we are of a broad, Karamazovian nature—and this is what I am driving at—capable of containing all possible opposites and of contemplating both abysses at once, the abyss above us, an abyss of lofty ideals, and the abyss beneath us, an abyss of the lowest and foulest degradation.

Fëdor Dostoevskij, The Brothers Karamazov

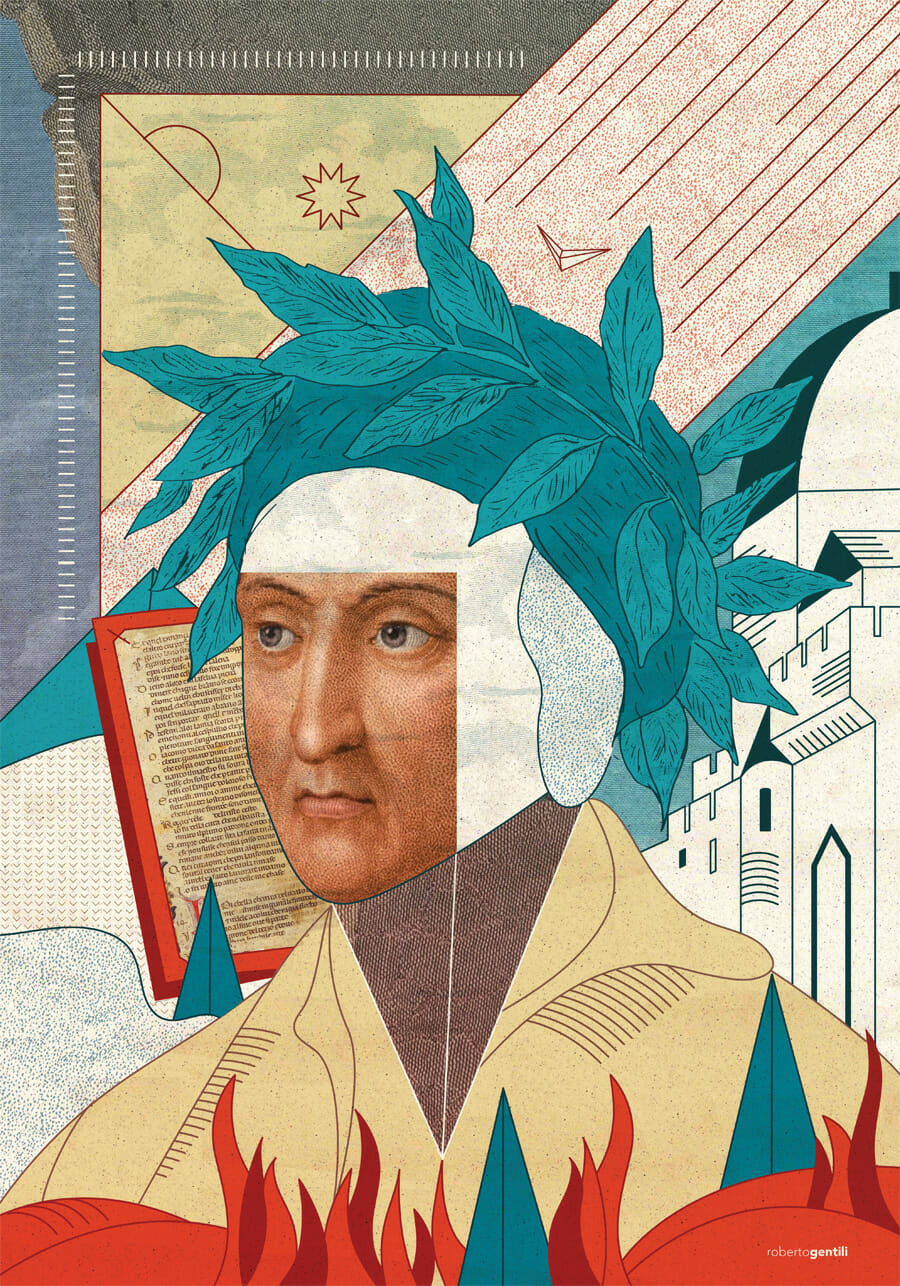

How long does it take it to go to Hell and climb up all the way to Heaven? Dante spent 14,233 lines throughout his Divine Comedy. For Diego Armando Maradona, it was a matter of four minutes.

Shadows of the war

On the 22nd of June, 1986, Argentina and England were facing each other in a quarter-final of the World Cup in Mexico. It was a much-anticipated match, especially given the very tense political relations between the two countries.

Over the match hung the shadow of the recent Falklands War. Four years before, Argentina had invaded the Falkland Islands, a piece of British sovereign territory, and Great Britain had dispatched a task force to retake the islands, a task which took 74 days.

As so often happens, football became a perfect metaphor to express the rivalry between the two countries. In that Mexico City match, much more than a World Cup semifinal was at stake. This was particularly true for Argentina, who lost the war, and for their most representative player, Diego Armando Maradona.

The journey of Maradona, part 1 – The abyss beneath

As Dostoevskij wrote in his last masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov, humans are able to contemplate both the “lofty ideals” and the “foulest degradation”. No other species can witness a most extensive range between the best and the worst it is capable of.

If Maradona’s life proves this statement quite clearly, those four minutes in the Argentina-England match of 1986 are the perfect summary.

After 51 minutes, a ball unexpectedly came from the right side of the pitch inside the England penalty box, which contained only the English goalkeeper Peter Shilton and Maradona himself. Although considerably smaller than Shilton, Maradona was able to deflect the ball into the net, punching it with his fist. The Tunisian referee Ali Bin Nasser was arguably one of the very few in the stadium not to notice it, allowing the goal among the British protests. The Hand of God was born.

Maradona called his fellow players to come and celebrate with him, not to leave space and time for the slightest doubt: for sure, not his most significant act of sportsmanship.

Who knows, maybe at that moment he felt that he had to do something to amend his metaphorical crime, in another common topos of Dostoevskij’s works.

The journey of Maradona, part 2 – The abyss above

It took four minutes for him to climb to Heaven. In the 55th minute, Maradona received the ball before the half-way line, protecting it from the attack of Peter Reid and Peter Beardsley. He was then able to run towards the goal, the ball glued to his left foot, dribbling Terry Butcher, Terry Fenwick, and Peter Shilton before gently putting the ball into the net.

Just four minutes after scoring with a hand, Maradona has already solved his debt with football, giving one of the most incredible goals in football history. In the aftermath of such a masterpiece, the Uruguayan Victor Hugo Morales famously asked Maradona during his live commentary:

Barrilete cósmico… ¿de qué planeta viniste? ¡Para dejar en el camino a tanto inglés! ¡Para que el país sea un puño apretado, gritando por Argentina!

Cosmic kite, which planet did you come from? To leave so many Englishmen behind! For the country to be a clenched fist crying for Argentina!

In four minutes, Maradona was able to contemplate both abysses. At first, by taking possession of a goal he did not deserve. Then, by creating an artwork that was never seen before on a football pitch.

Argentina ended up winning that World Cup, defeating Belgium and Western Germany on the way to the title, the second ever. A triumph achieved under the lead of Diego Armando Maradona, the most Karamazovian player ever.