During a walk along a path on the Ekeberg hill at sunset, with friends, while the sky turned blood-red, suddenly a man — and only he — heard an infinite, piercing scream, a sound that seemed to come from nature itself. From that experience was born one of the most famous paintings in world art. That man was the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, and the painting in question is The Scream, a universal emblem of human anguish, one of the most expensive paintings in the world, sold at auction for a record £119.9 million, and the subject of some of the most audacious art thefts of the 21st century.

On the 80th anniversary of Munch’s death and 40 years after his last Milan exhibition, his works return to the city. A vast exhibition at Palazzo Reale, organized with Arthemisia and Munchmuseet, showcases 100 works. The display includes paintings, drawings, and prints, offering a deep exploration of Munch’s artistic legacy. He captured humanity’s existential anxieties like no other 19th-century artist.

The exhibition, spread across a series of skillfully lit rooms, organizes Munch’s works around themes that were particularly dear to him: mental illness and family tragedies, ghosts, love and eroticism, male nudes and self-portraits, and finally, his relationship with Italy.

Melancholy and Bohemian Circles: The Early Years of Munch’s Life

The first section, entitled Allenare l’occhio, includes works such as Melancholy (1900-1901) and Kristiania Boheme II (1895). Like all of Munch’s works, both are inspired by biographical events, influenced by his friend and writer Hans Jæger, whose motto was: “Write your life!”

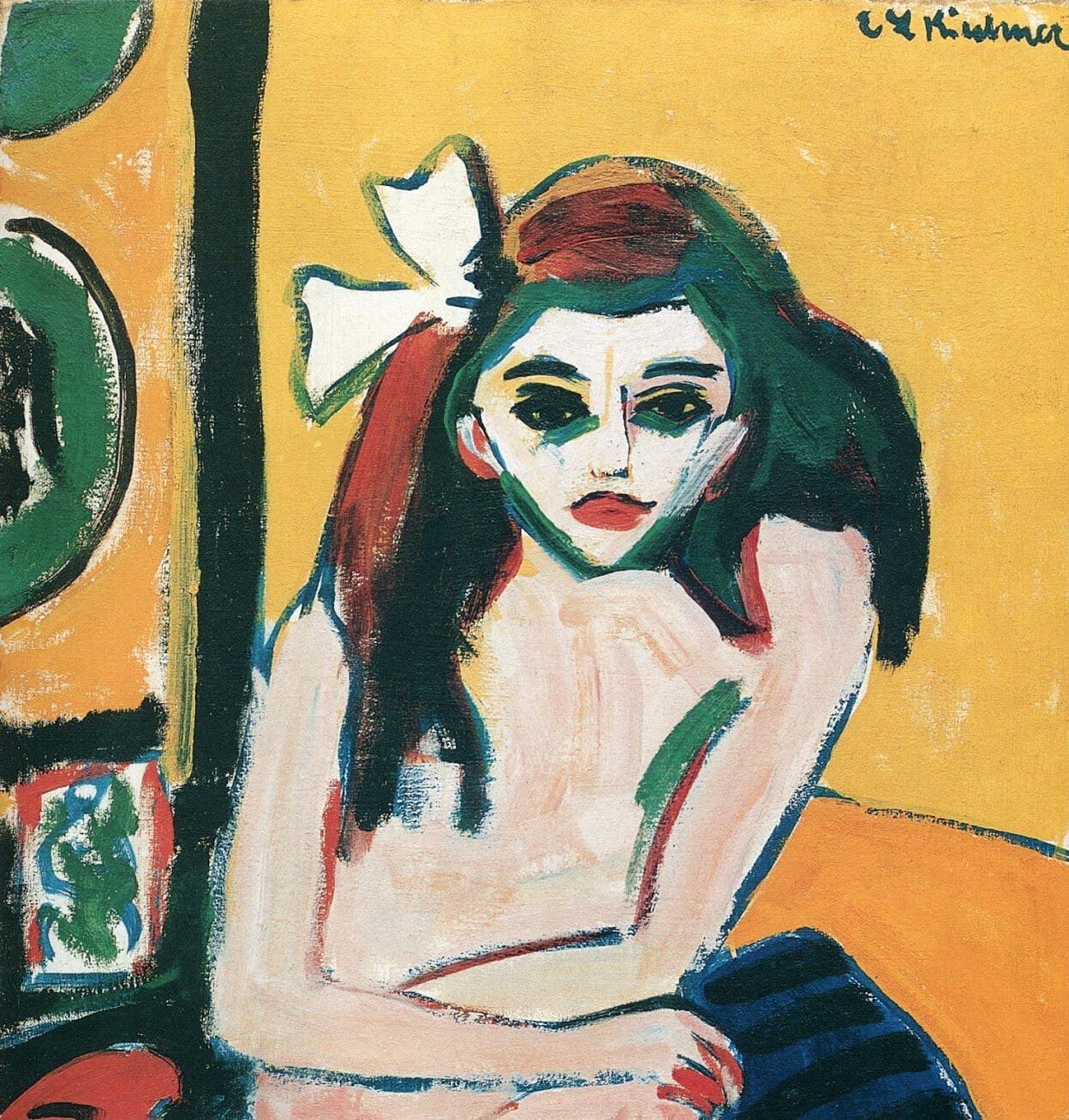

Melancholy depicts Munch’s sister Laura, whom the painter visited in the psychiatric hospital of Kristiania, where she had been admitted for hysteria and mental disorders. Her large, dark eyes, vacant and lifeless, express the deep inner trauma of the subject. A table shaped like a brain symbolizes the connection to mental illness.

Kristiania Boheme II, on the other hand, portrays the group of bohemian artists and writers Munch frequented in the 1880s. The group opposed bourgeois conventions, promoting free love and the excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs. Among the figures in the painting are Munch himself, Jørgen Engelhart, and the playwright Gunnar Heiberg.

Ghosts and Marionettes

The next section, Fantasmi, features some of Munch’s most famous works, including a new version of Melancholy (1891), Vision (1892), and the Set Design for Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts (1906), created for the homonymous Ibsen‘s play, staged in Berlin. Like Ibsen, Munch was fascinated by the repressed inner lives of his subjects. In the Set Design, he traps the characters in a claustrophobic setting, with a lowered ceiling and slanted floor, as though they were Ibsen’s marionettes in a dollhouse.

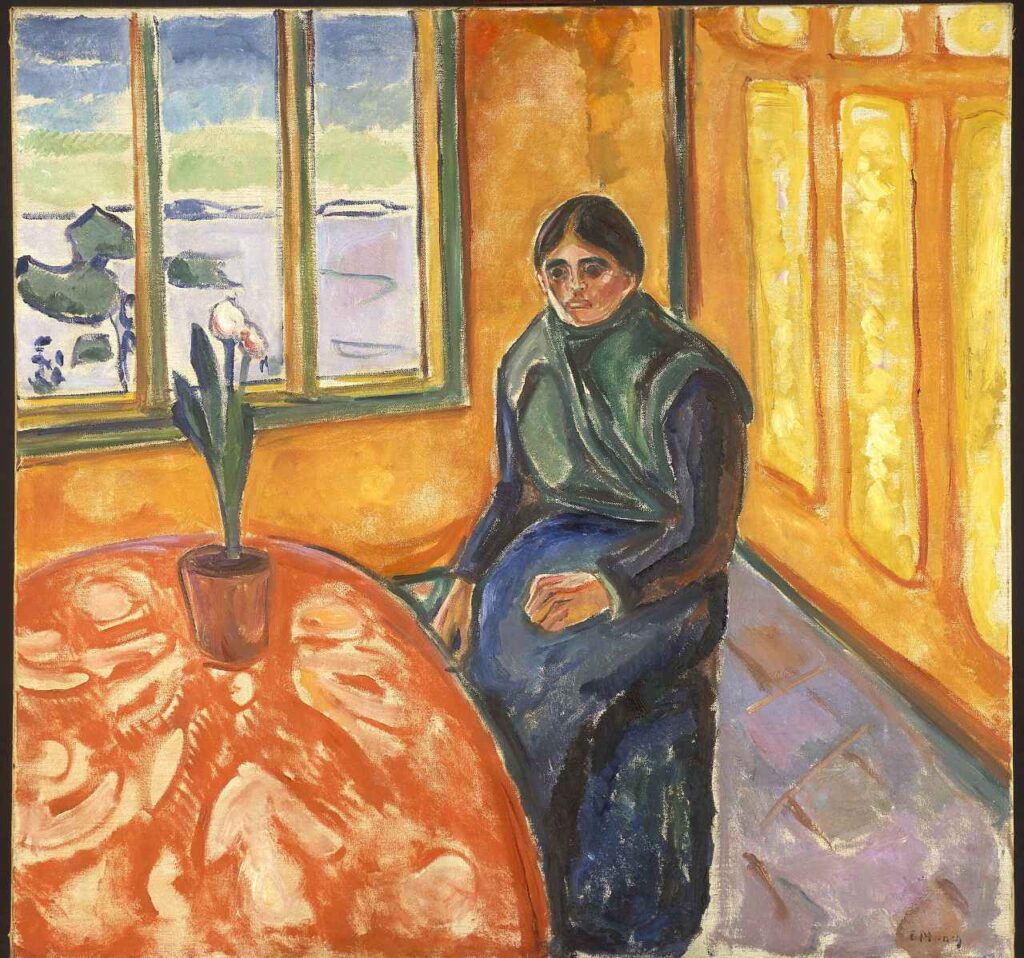

In Melancholy, Munch reinterprets (and would do so several times in the future) the theme with a new figure: a man. His posture is characteristic of melancholy, which Munch explores as a genuine psychological affliction, delving deep into the subject in many of his works. Vision is one of Munch’s most disturbing and complex pieces. A figure — somewhere between a fallen nymph and a zombie — emerges from what seems to be a stretch of water, or perhaps an artifact of the unconscious. The theme of closed eyes, popular in late 19th-century European Symbolism, evokes an escape from the physical world and a retreat into inner vision.

The Frieze of Life

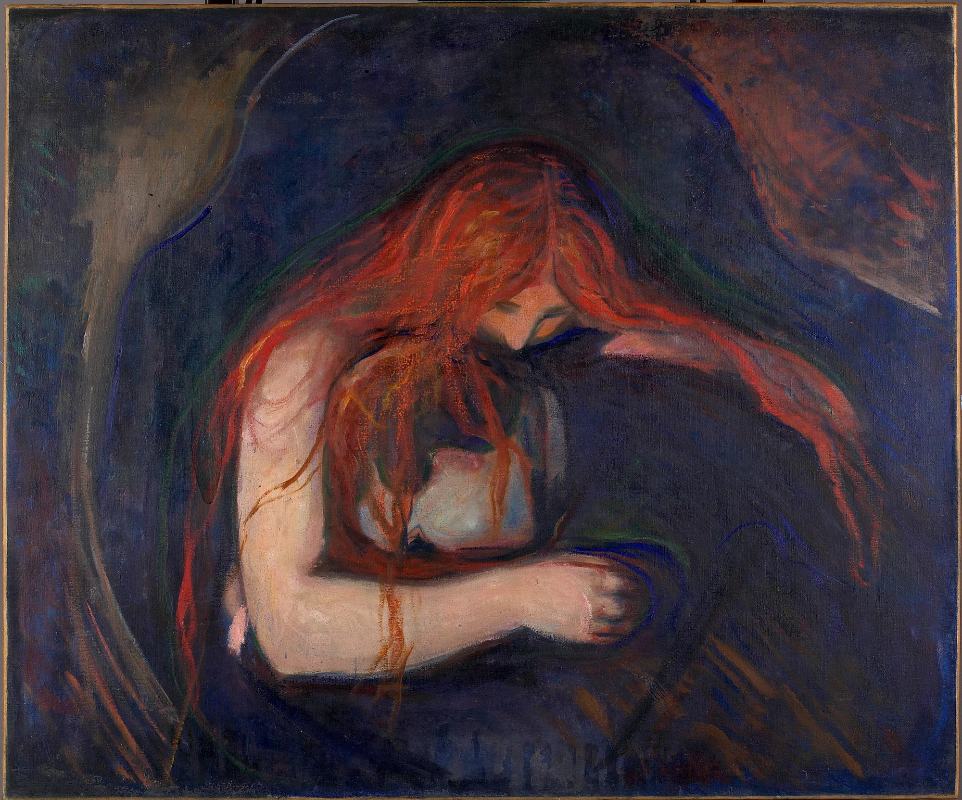

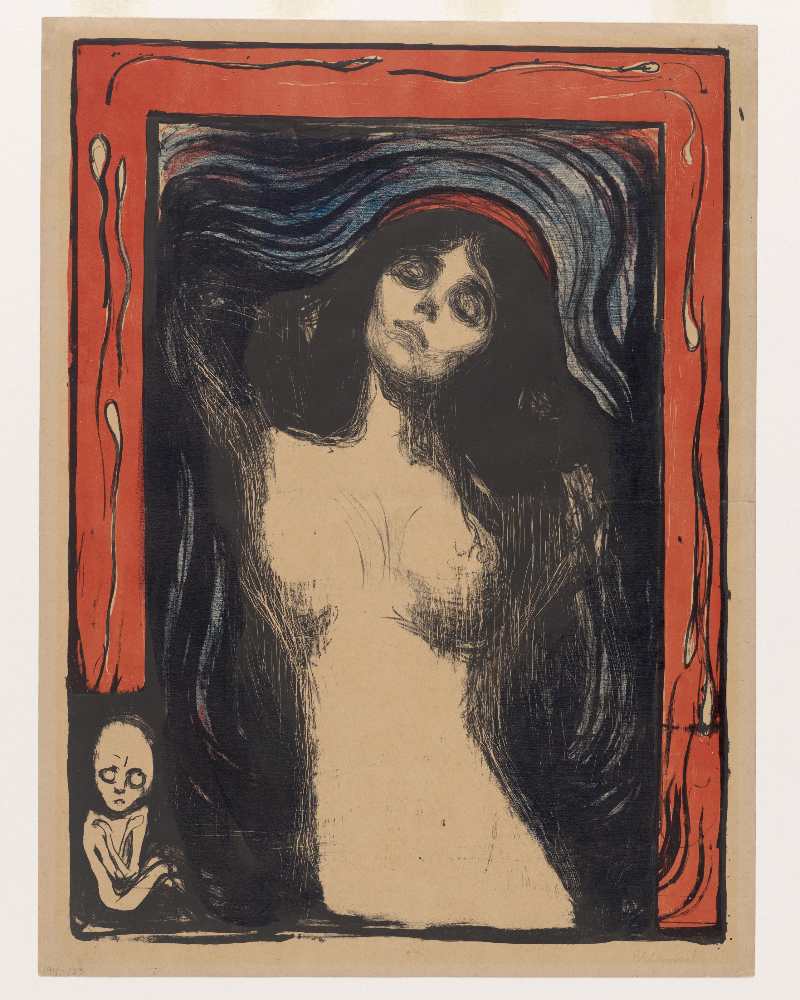

The next section — perhaps the most captivating — explores passion and eroticism, central themes in Munch’s life and work, with particular reference to his troubled relationship with Mathilde Tulla Larsen, which ended tragically with a gunshot. Here, works such as Vampire (1895), Madonna (1895-1902), Death of Marat I (1907), and Self–Portrait Against a Green Background are on display. This section reveals Munch’s view of women: sometimes innocent and Madonna-like, other times monstrous and dangerous. Thus, the woman becomes a harpy in the eponymous 1863-1944 work, with her claws bared as she hovers over her lover’s corpse, or a vampire sucking the blood from her lover.

In the early 1890s, many works here were included in a unified cycle called The Frieze of Life. The Vampire, initially titled Love and Pain, was renamed by critic Stanisław Przybyszewski, focusing on the man’s submission.

The Women in Munch’s Art: From Desire to Despair

The red (and less frequently black) hair of Munch’s women is a powerful symbol of vitality and passion, but also of danger and suffering. Hair color has always carried strong symbolic significance, as seen today in the blue hair of the rebellious Coraline in Henry Selick‘s animated film or, more fittingly, in the symbolism of color in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, where each hair color represents a phase in the protagonist Clementine’s life and her relationship with Joel. In Munch’s work, hair symbolizes erotic power, represented as a double-edged sword: on one hand, it cradles the face of the lover (in Vampire), while on the other, it envelops him in a suffocating grip (Man’s Head in Woman’s Hair,1896).

Madonna, one of Munch’s absolute masterpieces, of which five versions exist, depicts the bust of a nude woman caught in a moment of erotic ecstasy, with an expression reminiscent of Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. Her raven-black hair spread across her contorting body, and a profane halo of red represents passionate love and blood. The painting plays with the dichotomy of red and black, symbolizing love and death, much like Stendhal’s famous novel The Red and the Black.

Tulla Larsen and the Exhibition’s Closing Sections

An entire room is dedicated to Munch’s relationship with Tulla Larsen. The centerpiece of the room is The Death of Marat, a work that reinterprets Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting, in which Munch compares himself to the revolutionary murdered by Charlotte Corday. Tulla’s figure is portrayed as Munch’s assassin, symbolizing the pain and violence that marked their tragic love affair.

The following sections present numerous male nudes and self-portraits, such as the captivating Self–Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed (1940), where the artist portrays himself as an older man, surrounded by a clock and a bed — symbols of Thanatos (death) and Eros (life and desire), respectively.

The exhibition concludes with a section dedicated to Munch’s relationship with Italy, a country he visited several times throughout his life and where he drew inspiration from the works of great Italian masters such as Raphael and Michelangelo.

Munch, the Painter of Emotions

The exhibition on Edvard Munch provides a comprehensive overview of the key themes in his life and work: illness, mourning, love, passion, anxiety, jealousy, betrayal, and much more. The thoughtfully arranged display allows visitors to explore the various stages of the artist’s life, from his turbulent youth and involvement in bohemian circles to his retreat to his villa in Ekely, where he spent the final years of his life.

Munch, with his subversive and “maudit” approach, was one of the few artists to truly probe the depths of the human soul, bringing out the most profound and universal feelings: alienation, anguish, love, and passion. The painter invites the viewer to engage with these emotions by breaking the fourth wall with his characters’ direct gazes, the violent (yet symbolic) use of color, and the incisive lines. The exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in Milan, which will run until January 26, 2025, offers a unique opportunity to enter the creative workshop of the ultimate “painter of emotions”.