A history of red color in the arts | Red as an endless ocean

In August 2022, three very peculiar sculptures by French artist James Colomina popped up in Barcelona, Paris, and New York. Even in cities already full of different kinds of art, the statues could hardly pass unnoticed. And in the twinkling of an eye, their pictures made their way around the world. They portrayed Vladimir Putin riding a toy car-sized tank — and they were entirely red.

No matter if they portray the Russian President or Pinocchio, Colomina’s sculptures all have one thing in common: each and every one of them is glowing scarlet. The artist chose this color as his signature for a variety of reasons:

[My sculptures are] Red because it catches the eye in an urban context. And above all because you can say many more things with this colour than with others. Red can convey violence, beauty, softness, love…

James Colomina

Colomina’s observation could not be more accurate. Color, we know, is produced by an interaction of the spectrum of light with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. But colors are not just fragments of light, nor are they simply sensations. As with any symbol, the meanings we attach to them are conventional, which is why they can mean anything and its opposite. And even a single color — the very same shade of red — splits up into a spectrum if one goes through all of its different shades of meaning. Nowhere is this more true than in the case of red.

Michel Pastoureau is a French professor of medieval history, and expert in heraldry, and according to him «red is an endless ocean.» Hundreds of pages could be written on its innumerable meanings, and this vein would still remain unexhausted. Here, we will limit ourselves to recounting some of those that have resonated the most in the artistic sphere. Four little drops, as it were, taken from the infinite ocean of red.

Primordiality

For millennia, in the Western world, red has been the king of all colors. For a long time it was also the only one — at least if one considers its social role. According to anthropologists, red is the oldest word to be attested to denote a color, because it was the first shade we used as a dye. Along with black, the first materials our species used to alter the appearance of things around us were deep-brick-toned.

Quite inevitably, the oldest remnants of our figurative and craft history are thus colored red and black — the former obtained from loams and soils with a strong dyeing power, the latter from charcoal. That is to say, the whole history of arts begins with this specific pair of colors.

Altamira cave

Corinthian pixis with lotus buds decoration

Lascaux cave

Corinthian aryballos

But appreciating for real the extent of the primacy of red throughout human history requires a little stretch of the imagination. Let’s try to visualize it. At the dawn of mankind, in the deep of the Altamira cave, west of Santander in northern Spain, a hunter in an animal skin tunic paints the mighty bison on the walls of a cave. In a Corinthian workshop, several centuries before Christ, a slender-fingered artisan paints a winged horse on a vase. There are at least 10,000 years of human development between them. But the colors they use are the same: they all range from brick to carmine.

A shot from "Deep Red", by Dario Argento

The primacy of red in ancient societies doesn’t only have to do with its prevalence in practical use. Its symbolic value has been superior to other colors from time immemorial. This preeminence sinks its roots into the two main referents of red: fire and blood. These natural and vital elements form an almost immediate juxtaposition with this color. Blood is both a source of life and death, depending on whether it circulates in a body or flows out of it. The idea of blood as the nourishment of the gods was widespread in the ancient world. This is why human or animal sacrifice was commonly considered a communication form with them.

Its connection with such primal elements made of red a symbol of the most violent and uncontrolled instincts of us humans. Over the history of the art, it has variously signified passion, madness, ferocity, and frenzy. Such is the case for Dario Argento‘s cult movie Deep Red. One doesn’t need to be an art historian nor a cinema critic to realize that Argento’s “deep red” is the color of spilled blood: the color of murder. The color palette of The Shining, Stanley Kubrick‘s iconic horror, is also dominated by this unsettling shade.

But while primal passions are always perturbing, they are not necessarily negative. And the same stands true for primordial red. In his Elementary Odes, Chilean poet and Nobel Prize winner Pablo Neruda took the simplest object of his and our daily lives and elevated them to poetic subjects. He wrote verses for an onion, a bread of loaf, and even the air. And, of course, he could not miss an ode to one of the prime staples of every kitchen: the tomato, whose pulp he describes as a “red viscera.”

...Unfortunately, we must

murder it:

the knife

sinks

into living flesh,

red

viscera,

a cool

sun,

profound,

inexhaustible,

populates the salads

of Chile...

Pablo Neruda, "Ode to the tomato"

May it be carnage, passion, or gluttony, red always evokes primal emotions, and here lies the origin of its primacy throughout the centuries. No color has gathered as many layers of meaning as red because no color reminds us as strongly of the elemental dimension of our lives. This is why in ancient and modern cultures, it was always given a privileged position in the hierarchy of colors: because of its special ability to represent humans’ most basic experience. And precisely because of that, until a few centuries ago, those who wore it turned out to be just as unique in some way or another…

Power

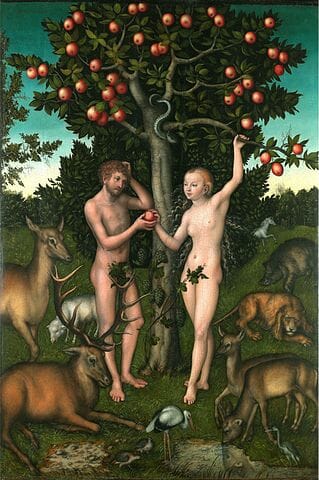

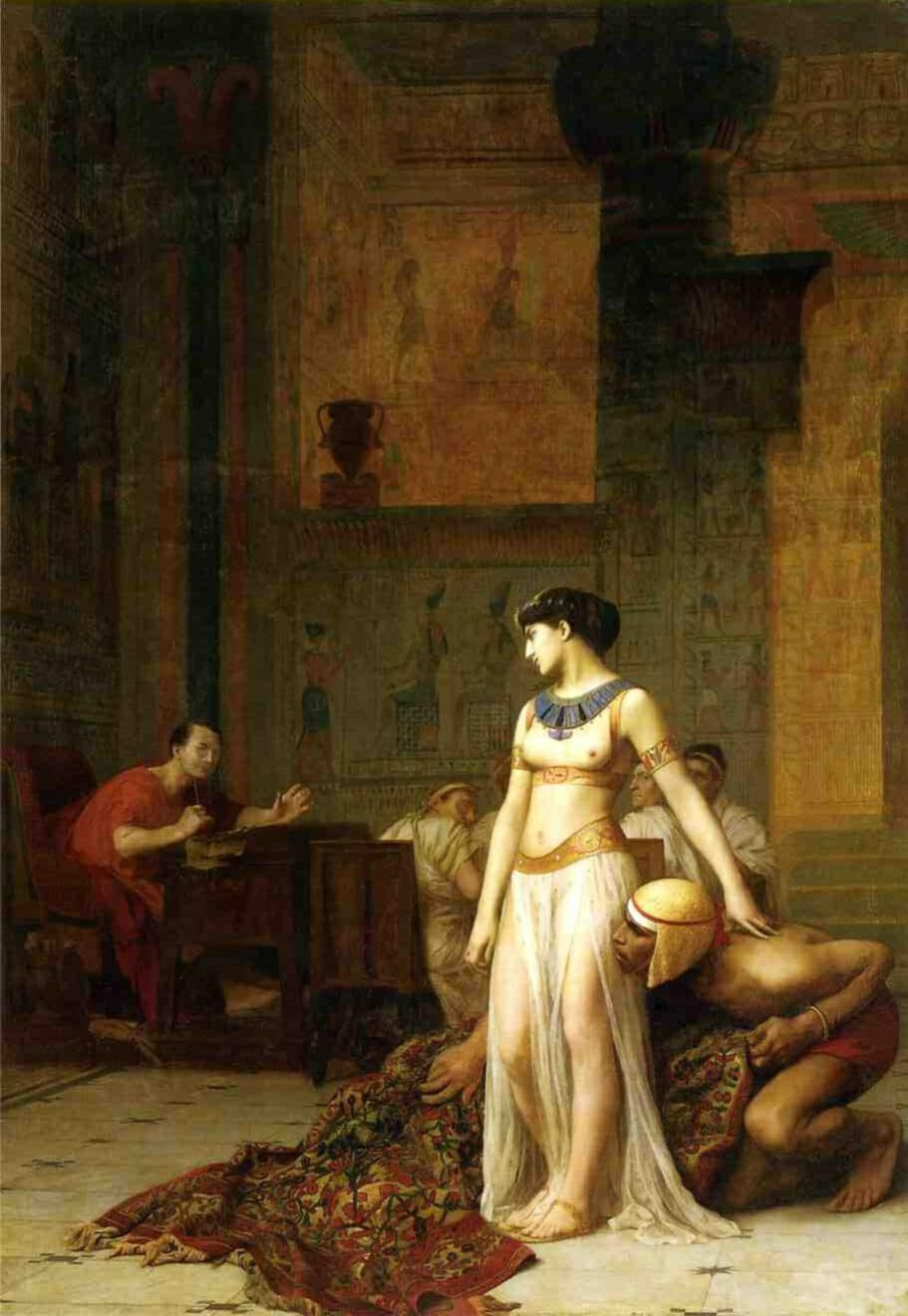

Cleopatra and Caesar

Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1866. Private Collection.

In the classical world, there was no pigment more precious than Tyrian purple. From as early as 1200 BC, it was produced from the liver of the murex, a small sea snail, and fifteen to sixteen pounds of its juice were needed to produce 324 grams of dye. A sign of wealth and power, from time immemorial the peoples of the Mediterranean have clothed their political and religious leaders in it. In the Roman Empire, the right to wear a dress or garment of this colour eventually became restricted to the exercise of priesthood, magistracy, or military command. But only one person was allowed to dress entirely in Tyrian purple: the Emperor, whose garments symbolised absolute authority and divine essence.

Over the centuries, some of the most powerful figures in the Western world adopted this symbolism. In Carolingian times, the emperor often sported red clothes and ornaments. This is why, for his coronation on Christmas Day 800, Charlemagne appeared before the Pope dressed entirely in red.

Not surprisingly, red was eventually adopted as a mark of power in the Catholic Church as well. The Christian symbolism of this colour is particularly important for the purposes of our research, as many of the past and present uses of red in the arts sink their roots right there. The system of meanings the Catholic Church built around red has developed to become profoundly contradictory. Again, it revolves around fire and blood, but both of these elements are considered for their good and bad aspects. The negative meanings are recounted in the ‘sin’ stanza. For now, we will stick to the positive ones.

Just as in ancient religions, fire and blood can boast a special role in the holy texts of Christianity as well. In the Old Testament, Yahweh often manifests himself through fire. And even in the New Testament fire represents an incarnation of the Holy Spirit, who came upon the apostles in the form of ‘tongues of fire’ on the day of Pentecost. For this reason, the Church has oftentimes associated red with God’s intervention.

But this profoundly primal colour also represents the blood of Christ and his martyrs — which in many cases is genuinely an object of worship for Christian communities. The world renown Neapolitan ritual of the dissolution of San Gennaro’s blood is only the most famous example of such devotion. Over the centuries, Christianity has evolved to become more and more the religion of red and blood.

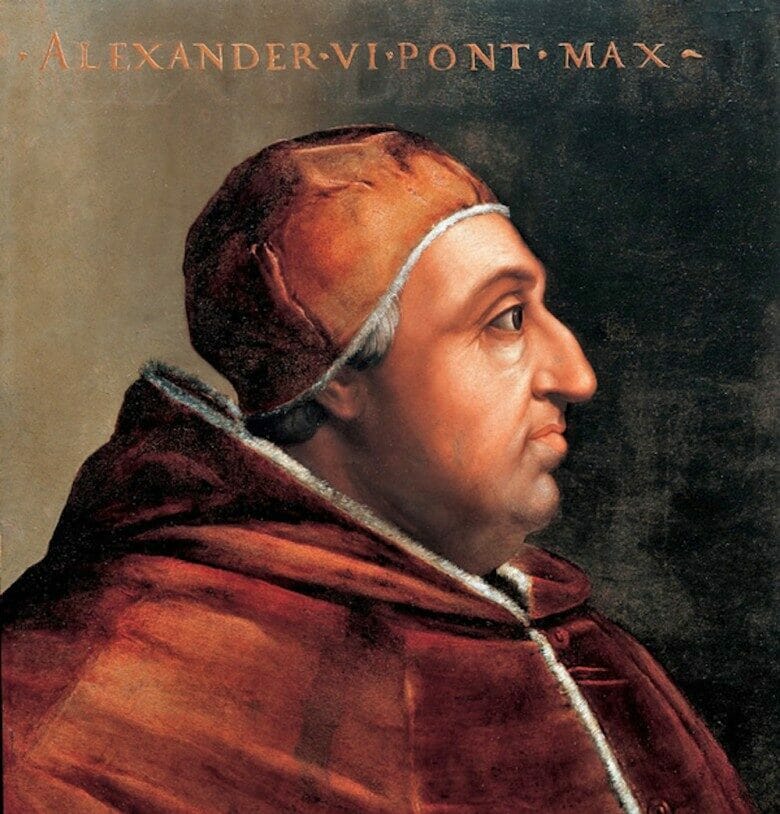

It should not come as a surprise that red became the colour dressing all the highest offices of the church. From the 16th century, the promotion to cardinal of a bishop or archbishop is indicated by the expression that they are now «wearing Tyrian purple». And until the end of the Middle Ages, even the Pope wore red and white. Even in present times, the so called “papal slippers” remain red.

Obviously enough, whether it is a painting by Raphael or a scene from The Young Pope, from the Middle Ages to the present day, all artistic representations of high church dignitaries shine in red.

A shot from "Three colours: Red", by Krzysztof Kieślowski

In the medieval West the colour red was closely linked to power in all forms. It was charged with punishing crimes and atoning for sins not only in the furnace of hell, but also in judicial rituals. Red was the colour of the magistrates’ robes. Red was the hood of the executioner and red were his gloves. And even if judicial dignitaries no longer wear it, this peculiar meaning of red has survived, in various forms, to the present day. Just think of a child’s homework. What colour normally are the teacher’s corrections?

In Three Colours: Red, one of Krysztof Kieślowski‘s most beautiful films, the young dancer Valentine enters into a life-changing friendship with a retired judge. The judge, who spends all his time spying on his neighbours’ phone conversations, has been widely described by critics a biblical figure. A God who sees all, knows all, and yet has stopped inflicting punishment. The colour palette of the film is entirely dominated by red.

Guilt

Over the centuries, red has been widely used as the color of power and judgement. But paradoxically enough, it is also the color of guilt. A mark that could indicate the most unforgivable degeneracies, especially in the Christian world.

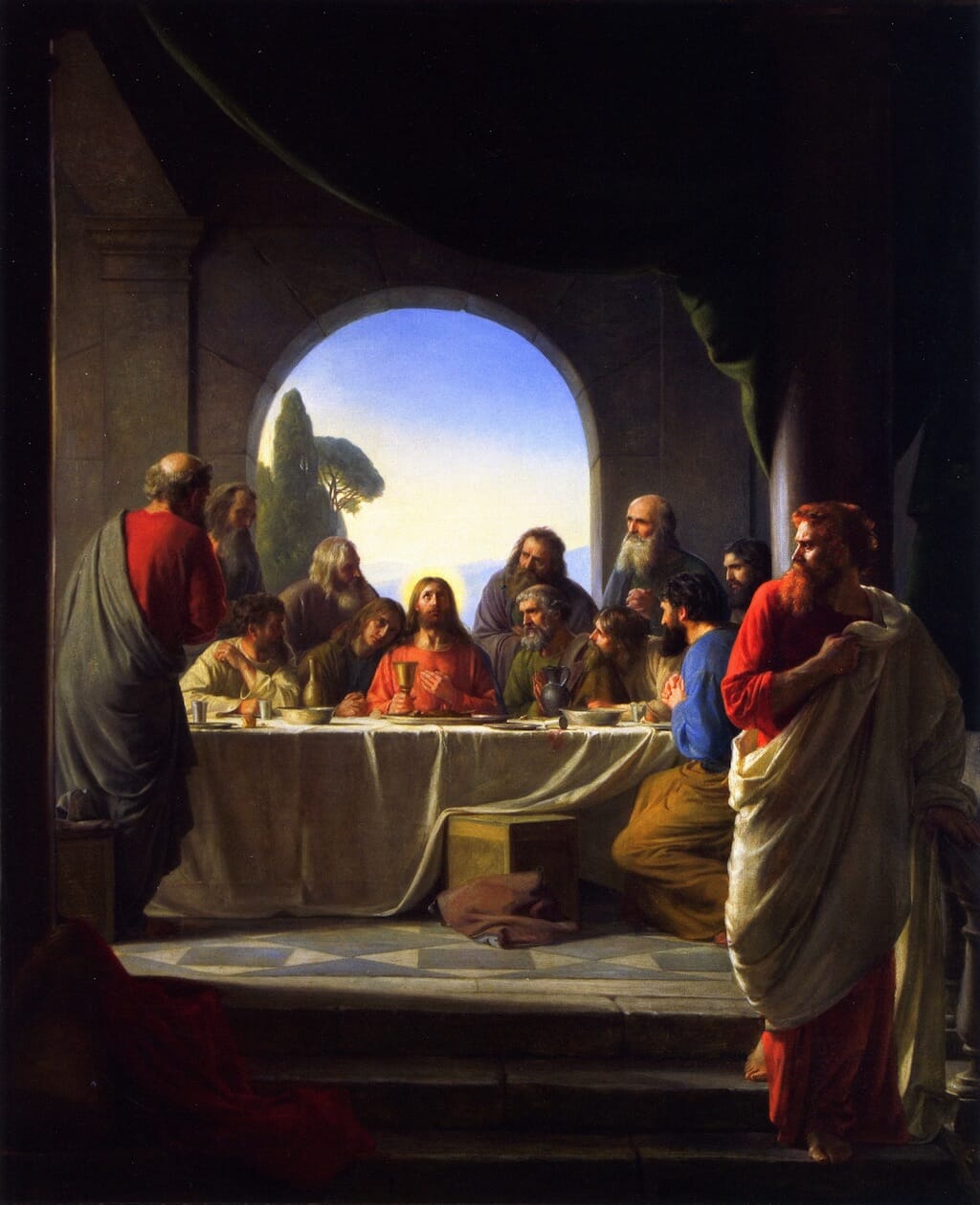

In its negative sense, Christian red almost always leads back to spilled blood or the infernal furnace. From the Middle Ages onwards, some of the most infamous characters in Christian sacred texts began to be depicted as red-haired people. Judas Iscariot and Cain are the most famous examples. This characteristic gradually extended to include all those who are considered outcasts.

Jews, heretics, vagabonds, lepers, they all seem to have one thing in common: the color of their hair.

Along with them, the reformed prostitute Mary Magdalene is one of the earliest and most consistent figures in Western art history to be portrayed as a redhead. In her case, however, red hair doesn’t simply signify sinfulness but sexual sinfulness.

When it stands for guilt, the symbolic power of red clearly bears a gendered dimension. Even at the times of the Roman Empire, red-headed women were considered to be lustful and depraved. This association is as true for hair as it is for clothes. At the end of the Middle Ages, specific municipal regulations obliged prostitutes to wear flamboyant clothing or ornaments to distinguish themselves from honest women. The prescribed color, most often, was red.

Even in more recent times, artists in all fields often recurred to red as a symbol of carnal sin — no matter that their works were in open conflict with patriarchy. In Nathaniel Hawthorne‘s novel The Scarlet Letter, the protagonist is forced to wear a red letter on her clothes to mark her as guilty of adultery. In The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood‘s world-renown dystopia, women are forced to wear different colors based on the social caste they belong to. The “handmaids,” who are expected to bear the children of the powerful, wear a red cloak and cap.

Revolution

With the end of the 17th century, the symbolism of red was enriched by a new layer of sense, which over the decades, overcame all others: the political one. Born out of the French Revolution, political red was first linked to the social struggles of 19th-century Europe and took on an international dimension in the following century. In many areas, the word “red” became an exact synonym of “socialist,” “communist,” “extremist,” or “revolutionary.” According to Professor Michel Pastoureau, «never before had a color embodied an ideology to that extent».

Eugène Delacroix , "Liberty Leading the People", 1830. Louvre

The rise of red as a political color originates with two textile objects. The so-called Phrygian cap and the red flag. For a long time, the red cap has been Europe’s most significant revolutionary symbol. This headpiece, widely used in popular circles, reminded scholars of the 16th-17th centuries of the cap worn by the freedmen of ancient Rome, who often came from Phrygia: legend has it that when the Phrygian slaves gained their freedom back, they would wear the red cap of their fathers.

It didn’t take long before the French revolutionaries took that symbol over, which is why it appears in so many paintings and pictures dating from that period. Eugene Delacroix‘s masterpiece, Liberty Leading the People, is one of the various examples.

The red flag, for its part, was originally a signal related to public order. The authorities would pull out a red banner to warn the people of an impending threat and to disperse them. And over the years, it had become progressively associated with the repression of rallies and even martial law. But in July 1791, its meaning was suddenly reversed.

The Jacobin movement was in its infancy. Revolt raged in Paris. All of a sudden, the mayor hastily raised the red flag, and without even giving the crowd time to disperse the National Guards opened fire. There were fifty victims, who were immediately proclaimed martyrs of the revolution. What really dyed the flag red, now, was their blood. From this moment on, the red flag became the emblem of every form of revolt. Victor Hugo’s lines on an old man raising a red flag in Les Misérables stand as one of this political symbol’s most beautiful artistic representations.

When he had reached the last step, when this trembling and terrible phantom, erect on that pile of rubbish in the presence of twelve hundred invisible guns, drew himself up in the face of death and as though he were more powerful than it, the whole barricade assumed amid the darkness, a supernatural and colossal form.

There ensued one of those silences which occur only in the presence of prodigies. In the midst of this silence, the old man waved the red flag and shouted:—

“Long live the Revolution! Long live the Republic! Fraternity! Equality! and Death!”

Victor Hugo, "Les Misérables"

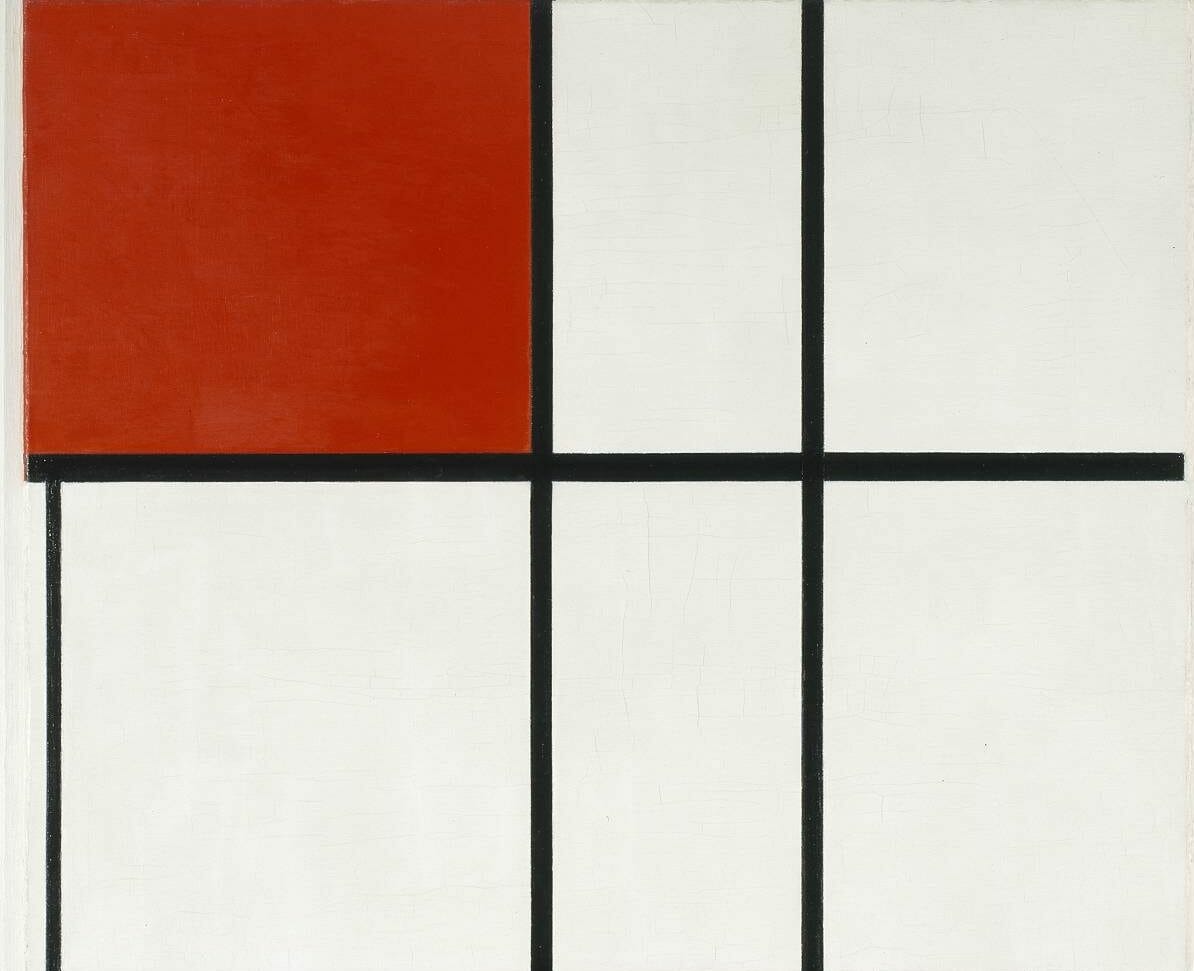

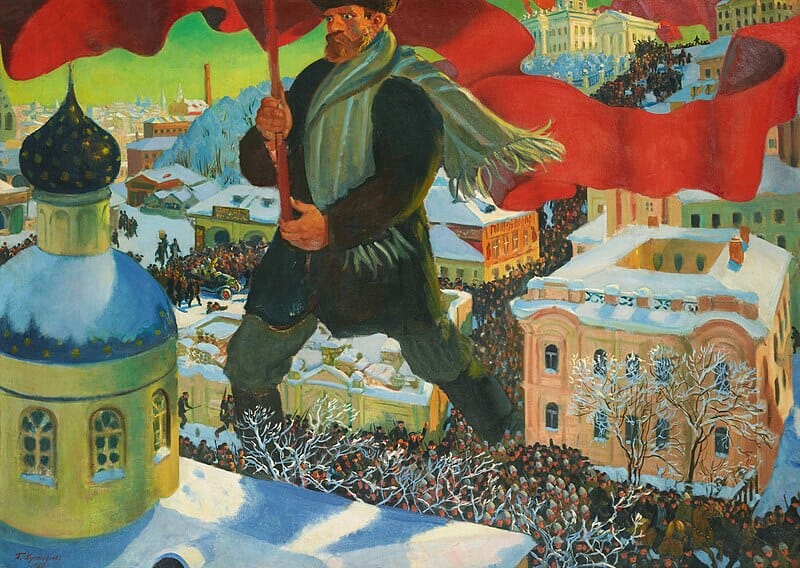

Eventually, the red flag would be embraced by left-leaning parties worldwide. And with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution, it finally got consecrated as a the ultimate symbol of communism. But revolutions do not only have to do with politics. As red flags took over the Russian Empire, the first avant-garde movements shook the foundation of modern art. That’s when Russian artist Kazimir Malevič founded Suprematism.

The avant-garde painter wanted to bring art to its zero point. In Suprematism (Part II of The Non-Objective World), he wrote:

Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in and for itself, without “things” (that is, the “time-tested well-spring of life”).

For this reason, Malevich’s works mostly depicted the fundamentals of geometry (circles, squares, rectangles), painted in a limited range of colors. One of his most well-known works, Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions, is a depiction of a red square on a plain white field. «Draw in your studios the red square as a sign of the world revolution of the arts,» Malevich wrote in 1920. And a revolution it was.

Since the dawn of humankind, red had meant anything and its opposite. Crime and punishment. Power and submission. Love and pain. It took thousands of years to get to Malevich’s intuition. To get red representing nothing at all. Just itself.

Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions

by Kazimir Malevich