The Defeat of Darkness

Today it’s incredibly easy: you press a button and CLICK! The room lights up, the dark corners of the house aren’t scary anymore, the strange, unsettling shadows are replaced by familiar furniture. A modern “let there be light” that nourishes mankind’s tendency to think itself invincible, in this neo positivist era we inhabit.

Defeating the darkness wasn’t always so easy. The value of light, therefore, has always been recognized and celebrated with symbolic meanings that have been renewed from century to century, while maintaining as a constant an extremely positive quality. In open contrast to the dark, then, which acquires, together with its synonyms, a meaning closely linked with death, oblivion, and sin.

The goal of this exhibition is to reveal the symbologies that light and darkness have come to embody in the different contexts of mankind’s artistic creation.

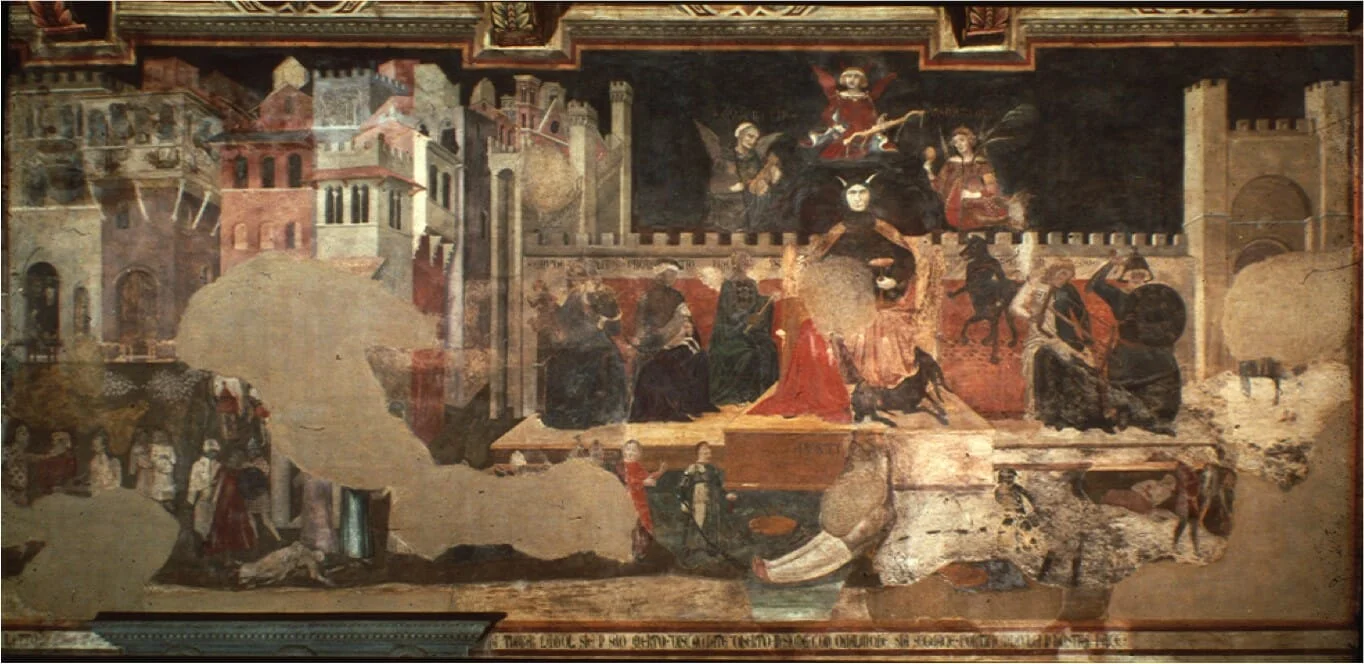

The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

One often hears about the light and dark sides of politics, and yet to render the dichotomy overt is this fresco by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. The juxtaposition is intended to educate about the consequences of the two forms of government, tyrannical and comunal. But the tones used in the fresco also speak volumes. The joyful city, sun-kissed and peaceful, sits in open contrast with the murky hues of the terror-stricken city, shadowed by the omen of war and death.

Real lessons in civic education are hosted on the walls of a small room in the Italian city of Siena. The Salon of Nine, Siena’s dominant government from 1287 to 1355, used to meet here. It’s also the location for Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government. A work of art that comes with a didactic aim.

In fact, it doesn’t feature a single figure without an explanation of their identity underneath. Tyranny sits on the throne of the Bad Government, flanked by Greed, Pride, and Vainglory. At their feet lies Justice, tied up and abused. Violence has devastated the landscape surrounding the scene: the city is crumbling, and war rages beyond the walls. On the other hand, the Good Government seats the Township on its throne. Close by are the cardinals and theological Virtues. The city’s effects are those guaranteed by an ideal administration: buildings under construction, a teacher with a class of children, and a carol of women in revelry.

The Sienese style

In the first half of the 1300s, Siena was the beating heart of the Italian Gothic. The Lorenzetti brothers (Pietro and Ambrogio), along with Simone Martini, are the founders of a painting style that would have a historical impact on Italian art in the following decades, through to the late 1400s.

The exquisite Sienese style inherits an important trait from the cycle of Assisi frescoes by Giotto (and his school). It is the realistic representation of the everyday. This characteristic reveals the artist’s intent to make these painted stories more concrete, allowing the public to identify better. Today, we would call it an “immersive experience.”

This is the great power of The Allegory of Good and Bad Government. Through examples taken from everyday life, recognizable to its entire audience, it produces an effective declaration of political and didactic intent.

The Raising of Lazarus

In this piece the viewer is faced quite literally with the theme of the return from the dark towards light and life. Even being heavily damaged, the work by Caravaggio manages to represent the miraculous nature of the Raising of Lazarus. In this catacomb-like setting of funereal darkness, the figures emerge like lightning in flashes of white, through the powerful vibrato of divine illumination that floods the subject, bringing him back to life.

In 1609, The Raising of Lazarus‘s painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was fleeing from the latest mishap he had gotten into. Passing through Messina, the Lazzari family commissioned him for a canvas. Their last name inspired Merisi, who suggested the theme of the Resurrection of Lazarus, an idea they warmly welcomed.

Darker an existential tones

Here the darker tones that would characterize the latter part of his career first make their appearance. The body of Lazarus shows muscles by then gone soft. He is placed at the center of the scene in a pose reminiscent of a crucifixion (in the Gospels this episode foreshadows the Resurrection of Christ).

Differing from other works with the same subject matter, the protagonist of this canvas is not Jesus, but Lazarus himself. It’s not He who works miracles, but he who experiences them. From this point of view, the episode takes on more intimate, existential tones. It’s not hard to imagine how Caravaggio identified with that body asking for salvation from death and sin.

Like a film director

From a stylistic point of view, The Raising of Lazarus is an important example of one of the great innovations that Merisi would bring to painting (and sculpture) of the 1600s. The use of light is for instance pioneering for the way Caravaggio calibrated and guided it. It is comparable to the study of light that a film or theater director would make.

In The Raising of Lazarus, Caravaggio spotlights his stage and symbolically directs the light. He highlights Jesus’s arm and shoulder, landing in a strip of salvific light that floods over the body of Lazarus. Painters like De La Tour, Gentileschi, and Honthorst would later adopt this element as an inheritance from the master.

A detail from The Raising of Lazarus. Image Credits: The Raising of Lazarus – Wikimedia Commons

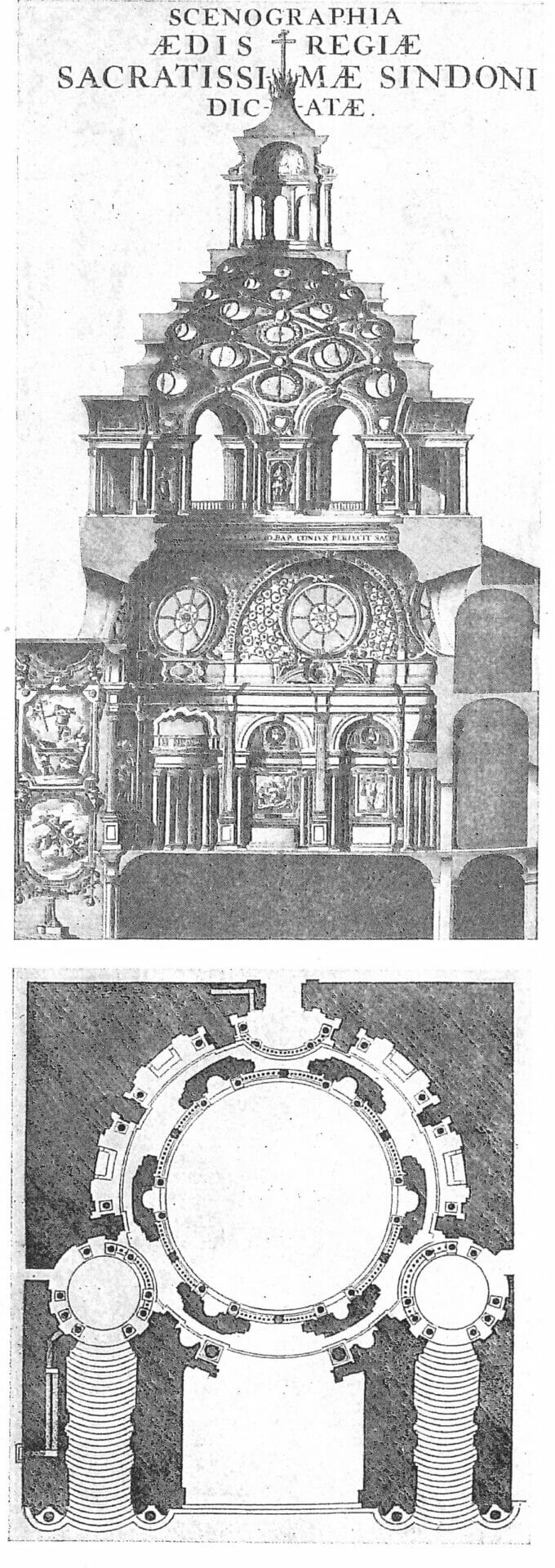

The Chapel of the Sacred Shroud

The passage from dark to light is sometimes closely linked with upward movement, as in the journey designed and realized by Camillo Guarino Guarini inside the Chapel of the Sacred Shroud. The route begins in two dark flights of stairs, made from shiny black marble. The many low steps recall the obstacles and trials of earthly existence. But already towards the end of the stairs one begins to imagine the promise of salvation that waits ahead. Entering into the chapel one is immersed in gray marble, that through the geometry of the structure drives the eye towards the top, emanating with light thanks to the openings in the chapel and lantern.

Camillo Guarino Guarini was not the first to work on a project on the Chapel of the Holy Shroud. Before him, the Savoys had commissioned Carlo and Amedeo Castellamonte and Bernardino Quadri. But finally, they entrusted it in full to the architect-priest Guarini, who used it as an outlet for all of his devotion, imagination, ingenuity, and ardent love of architecture.

The chapel is located between the apse of the Dome of Turin and Palazzo Reale.

A towering house of cards

From the outside one can appreciate only the conically shaped lantern, vaguely Asian in design, dotted with small urns that bring to mind the “pseudo-sepulchral” function of the structure

The interior, on the other hand, develops an immersive and experiential journey starting from two lateral portals at the high altar of the Dome. Here appear two flights of low steps, made from the same black marble as the walls and vaults. The stairs arrive at two vestibules, both black as well, opening onto the circular plan of the chapel. This is composed of five chapels, but what is most noticeable is the change in color.

A theatrical impact on the viewer

One enters into a gray space that becomes lighter and lighter as the gaze raises towards the cupola’s internal summit, which consists of a succession of six registers of arches becoming progressively smaller. They result in a telescopic effect that creates the illusion of stretched dimensions of the lantern. The impression is that of finding oneself in a towering house of cards.

Image courtesy of Guilhem Vellut, via Flickr / Creative Commons

The journey from the earthly realm’s darkness towards the extraordinary light that glares through the cupola’s windows is highly symbolic. With his Chapel of the Holy Shroud, Guarini demonstrated his esteem for gothic architecture, which his contemporaries then denigrated. Furthermore, he declared his allegiance to the renewed architecture that took inspiration from Francesco Borromini. Unlike the Maestro, however, Guarini bends architecture to his own taste, favoring, as R. Wittkower says, “intentional incongruities and surprising dissonances.”

The Triumph of Death

A dark moment in Medieval history was the outbreak of the plague, that beginning in 1347-48 and through to the following decades touched many epicenters across Europe. The Black Plague takes its name from the dark marks (subcutaneous hemorrhages) that covered the bodies of its victims. That black of the infected and of the epidemic also conditions the tonalities of the painting. Art becomes dark and the light of salvation ever rarer. Soon the allegory of the Triumph of Death spreads, and the one conserved in Palazzo Abatellis is a precious example.

The Triumph of Death was a widespread image starting from the late Middle Ages and has its origins in Franco-Germanic territory. Often connected to the Last Judgment theme, it carries a taste for the macabre that will characterize the years to follow, up until the Black Plague of 1348.

A recurring image

The work’s location is the Abatellis Museum, in Palermo, Sicily. The painting belongs to a historical period that critics defined as International Gothic or court style. The majority of the fresco represents the same noble court. Death, embodied by a skeleton, rides astride an emaciated horse that tramples the lifeless bodies beneath it.

The scene’s grim protagonist has just released an arrow at a young man (in the bottom right). Pierced through the neck, he falls to his knees. The arrow is particularly symbolic in this context. Since the classical age, artists have used it to represent the unleashing of a plague on the part of divinity. For this reason, San Sebastiano, who appears in this iconography, having survived the executioners’ arrows, became one of the protecting saints against epidemics.

The didactic purpose

The Triumph of Death has a clear internal division, so much so as to be didactic. On the left, the author depicted a group of impoverished men and women, praying to Death to end their suffering. In the center, foreground lies the bodies of monks, nobles, and other members of the ecclesiastical orders. This shows Death does not make class distinctions.

Lastly, on the right, only the aristocrats near the center are upset by the macabre spectacle. Those towards the edges, on the opposite, appear either ignorant or serene, dedicated to their music and hunting. And yet Death is coming for them too.

Image courtesy of José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro – 2015 Wikimedia Commons