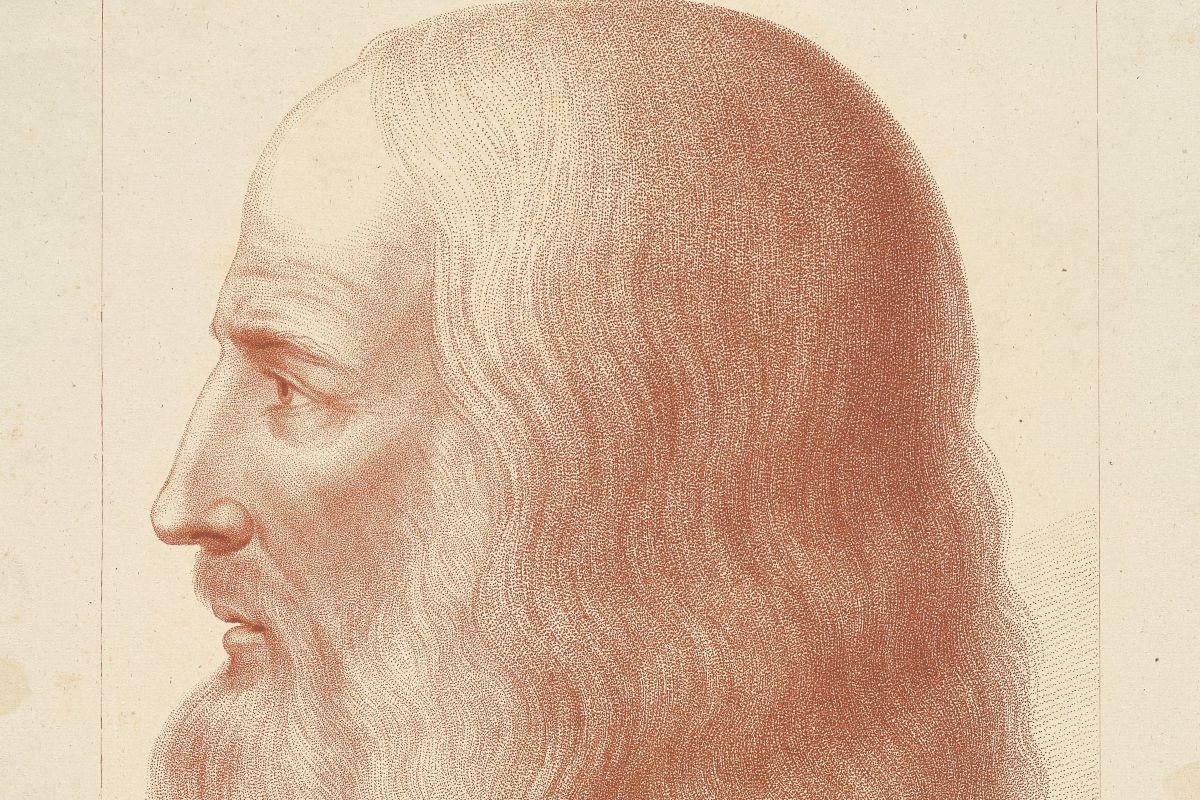

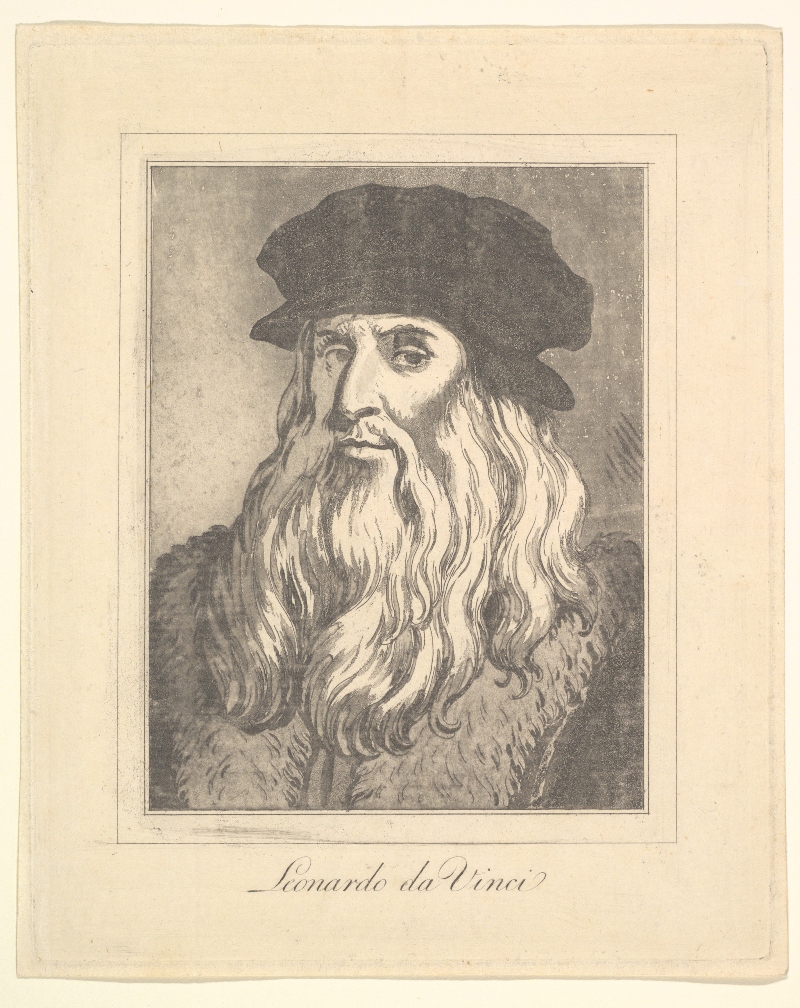

On May 2, 1519, in Amboise, France, Leonardo da Vinci died at the age of 67. A Renaissance genius par excellence, his ingenuity spanned the figurative arts, science, architecture, and engineering.

Over time, his name became synonymous with some of the world’s most famous works of art: the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper, and the Virgin of the Rocks. Various legends have arisen around them, playing a decisive role in the process of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘deification’. Today, a contemporary myth.

Leonardo da Vinci | The Man behind the Myth

Leonardo was born in Anchiano, a Tuscan village near Vinci, in the province of Florence, on April 15, 1452. The illegitimate son of notary Ser Piero da Vinci and a woman named Caterina, he moved to Florence in 1469. In the city of the Lily, he entered the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio. A painter, dear to the Medici family, who dominated the artistic scene of the time. At his workshop, the young Leonardo da Vinci took his first steps, learning painting techniques, studying from live models, and dissecting anatomy. The master’s influence is visible in the young artist’s early works.

In the Annunciation (ca. 1472, Florence, Uffizi Galleries), for example, Leonardo da Vinci sets the scene, as usual, in a meticulously reproduced garden. The Madonna is calm and undaunted by the Archangel’s apparition. The work shows attention to light, perspective, and realism, with details studied from life. In general, it does not depart from the tradition and example of Verrocchio, who is indeed explicitly cited. The elegant marble lectern used by Maria is inspired by the forms of the sarcophagus of Piero il Gottoso—a work created by Verrocchio in the church of San Lorenzo in Florence.

It was with his arrival in Milan in 1482 that Leonardo, inspired by the Lombard school and sensitive to the study of light, developed a more nuanced and less defined technique.

Between Lights and Shadows | Leonardo’s Masterpieces

To the Milanese years, spent at the court of Ludovico il Moro, belong some of the most famous works. In the London version of the Virgin of the Rocks (ca. 1491-1506, London, National Gallery), we can see how Leonardo da Vinci’s painting matured. The painting depicts the Virgin Mary with Baby Jesus, St. John, and an angel, set in a rocky landscape. In the background, Leonardo describes the outline of a mountain range, inspired by the Alps, which he could see from Milan. The atmosphere is evocative due to delicate shading, which enables soft transitions between light and shadow, lending greater realism to the work.

Another cornerstone of Leonardo da Vinci’s Milanese activity is The Last Supper (1495-1498, Milan, refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie). Here, the painter revolutionises the sacred scene with a dramatic and realistic composition. He focuses on the ‘motions of the soul’, on the reactions and emotions felt by the apostles upon learning that a traitor is among them.

Leonardo Man of Science

Leonardo, however, did not limit himself to painting. At the court of Ludovico il Moro, he was also involved in set design, engineering works (he made, for example, the Navigli navigable thanks to a system of locks) and scientific studies, devising war machines or contraptions that became famous, such as the aerial screw, the ancestor of the modern helicopter. To his code, Leonardo entrusts his inventions and studies. He thus creates an ante litteram encyclopedia, where he tries to capture almost every aspect of the world around him.

He also entrusted to paper a study on the proportions of the human body, better known as the Vitruvian Man (Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia). The work depicts a naked man inscribed within a circle and a square, symbolizing the harmony between the human body and geometry. Leonardo demonstrates knowledge of the theories expressed in De Architettura by the Roman architect Vitruvius, who gives the drawing its name. By combining art and science, he shows us man as the measure of all things.

Leonardo’s Last Years | The Smile of the Mona Lisa

Following the expulsion of Ludovico il Moro, a long period of wanderings began for the Florentine artist. He will arrive, finally, in France at the court of Francis I. Arriving on French soil, however, is not only Leonardo da Vinci. He brought with him some of his works, including the Mona Lisa (ca. 1503-1506), now housed in the Musée du Louvre in Paris. Famous for its enigmatic smile and direct gaze, the work shows a perfect balance between figure and landscape, thanks to the use of sfumato. The woman’s face delicately emerges from the shadows, conveying a sense of mysterious serenity.

Mythologized, lauded as one of the absolute masterpieces of Renaissance art, the subject of extravagant theories, the Mona Lisa, from being a portrait like so many others, has over time become a true pop icon. So has its creator. And you know, if an image becomes iconic, it is not exempt from uncontrolled reproductions, manipulations, or even desecrations.

Desecrating Leonardo | The Moustache of Marcel Duchamp

Perhaps only an artist as brilliant as Leonardo da Vinci could succeed in violating, with intelligence and sagacity, the sacredness of the Mona Lisa. Marcel Duchamp. The latter was one of the most influential French artists of the 20th century. Known for revolutionizing modern art with his conceptual provocations. After debuting in Cubism and Dadaism, he introduced the concept of ready-mades. Ordinary objects turned into works of art, such as the famous Fountain (1917, London, Tate Modern), which is an inverted urinal. The question Duchamp poses to us is: What is truly art? Is it enough for an artist to sign an ordinary object to make it a work worthy of being in a museum?

Among Duchamp’s most famous and provocative ready-mades is L.H.O.O.Q. (1919, New York, private collection). It is a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, to which the artist drew a moustache and goatee, adding the words “L. H.O.O.Q.” underneath. Read in French, the acronym sounds like “elle a chaud au cul” (“she is hot on the butt”), an ironic and irreverent phrase.

With this work, Duchamp criticizes the traditional idea of art as a sacred and untouchable object. He mocks the cult that often surrounds works, with the Mona Lisa being the most glaring example.

Leonardo Pop Icon | The Last Supper by Andy Warhol

The iconic charge that Leonardo’s paintings have acquired over time could not be ignored by one of the fathers of Pop Art. Andy Warhol.

An American artist, he began his career as an advertising illustrator. He later became famous for his works inspired by mass culture. By serially reproducing images of stars, such as Marilyn Monroe, or iconic everyday objects, like Campbell’s Soup cans, Warhol transformed art into a collective media phenomenon, in a word: popular.

And what artist of the past became iconic to the point of becoming ‘pop’ if not Leonardo? So here Warhol uses The Last Supper for The Last Supper series, made between 1984 and 1986. Warhol reworks the iconic religious scene with his pop style. He uses silkscreens, bright colors, and repetition of the image to turn it into an object of modern visual consumerism.

He often superimposes commercial symbols on the sacred image. Thus contrasting the spiritual value of the original work with the materialistic and media culture of the 20th century (The Last Supper, 1986, New York, MoMA). It is a reflection on the role of religion, art, and advertising in contemporary society.

Balance and Imbalance | The Vitruvian Man according to Mario Ceroli

Another artist who interfaces and reinterprets Leonardo da Vinci in a modern key is the Italian Mario Ceroli. The latter began his career as a ceramist. In the 1960s, he developed an original artistic language, mainly using raw wood to create human silhouettes and objects.

Among his best-known creations is L’uomo di Leonardo (Leonardo’s Man, 1964, in the artist’s collection), his interpretation of the Vitruvian Man. Ceroli developed several variations of it. An early wooden version dates back to 1964. Ceroli gives it his features. Leonardo’s man is thus the artist himself, who self-portrays himself as the Vitruvian Man.

Three years later, Ceroli returns to the theme. He conceived a new monumental Vitruvian Man, this time entitled Squilibrio (Unbalance), a version of which was also donated to Vinci. Here, the Leonardo figure expands in space. It becomes three-dimensional, being inserted into a cube and many spheres. Ceroli’s purpose is to make himself the spokesman and develop Leonardo da Vinci’s reflections on the world and its mechanisms. He integrates the Vitruvian Man into the reality of things. He subjects him to gravity and the laws of physics. The imbalance that gives the installation its name thus does not refer to it. But to that in which it is dropped. And that is to an everydayness that is anything but harmonious as Leonardo imagined it.

Nouveau Louvre | What Future for Leonardo?

Ultimately, Leonardo da Vinci, from his own time to the present day, has always been a landmark. His fame can hardly wane; indeed, his myth is constantly being nurtured.

Suffice it to say that in 2024, there were about 9 million visitors to the Louvre. The figure is set to grow. Indeed, on January 28, 2025, French President Emmanuel Macron announced an ambitious renovation project for the Louvre. The “Nouveau Louvre”, among its highlights, also has the creation of a room dedicated exclusively to the Mona Lisa. The latter is designed to improve its display conditions and better manage the influx of visitors.

Leonardo da Vinci is not just a name etched in history. He is living proof that human curiosity, intelligence, and the drive to push beyond the limits of knowledge can endure through the centuries. From a meticulous and reserved artist to a mainstream phenomenon, Leonardo has shaped the history of art, science, and thought, remaining a vital figure of the past, the present, and the future.