The second season of House Of The Dragon will be released on June 17th, and 2024 is the Chinese Year of the Dragon. This makes it such a successful year for the fiery creature. In movies such as Harry Potter (2001-2011), The Hobbit (2012), and Dragonheart (1996) or TV series like Game of Thrones (2011-2019), our imagination always finds these monsters attractive.

Dragons are always appreciated: they are fascinating, fabulous, and, at the same time, terrifying. They are represented in art by numerous images, as well as in films and heraldry. The colors of their scales, superb presence, and magical and sometimes redeeming powers somehow manage to draw in many people. Despite this, dragons have appeared in legends and myths as somehow purely terrifying and menacing by devouring virgins or spreading death through their fiery breath. In the art world, the modern painters who have depicted dragons are countless, going from Rubens to the Pre-Raphaelites.

@gameofthrones SUMMER 2024. #HOTDS2 ♬ original sound - Game of Thrones

- Once upon a dragon: the cosmic role of the dragon in ancient cultures

- From the Greek dracon to the wyvern

- The Eastern benevolent dragons

- Dragons in Western Middle Ages: The Monstrous Serpent of Hell

- Red, long, winged: what does a dragon look like?

- Saints versus dragons and dragons versus saints

- A special saint slayer

- Contemporary dragons: literary models

- When dragons became animated

- 21st century dragons: a huge variety of beasts

- Looking at the authentic dragon

Once upon a dragon: the cosmic role of the dragon in ancient cultures

Figures that bring to mind a snake-dragon have always been popular in mythology, particularly in ancient civilizations. Among the most commonly represented, there is the Ouroboros. It is a magical symbolic creature that swallows its tail, present in many cultures, such as the Maya. This beast is a positive symbol of renewal, rebirth, and endless return. It is also included amongst the alchemical symbols as it represents the unity and the prima materia of the universe.

The word itself, if written “oroboro,” results in a palindrome, adding fascinating detail to this myth. Representations of this beast can vary, but they always bring to mind a snake, and, in some cases, a proper dragon. In ancient cultures, they sometimes accompanied powerful members of the community or protected villages and towns. In general, they were linked to water, and often they looked more like snakes than monsters with legs and wings.

Jasper intaglio: Seated Serapis on crocodile, 2nd century CE, Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

From the Greek dracon to the wyvern

In antiquity, tradition narrated that they came from the east, from the areas around modern India. However, the word dragon comes from the Greek δράκων, in Latin draco, thus it was not used in pre-Hellenic cultures. Indeed, the first dragons appear in Sumerian mythology.

Towards the end of the third millennium B.C., the dragon myth joined that of Egypt, inspiring the legend of the demon of darkness, the sea-serpent Apophis. Even Seth, the brother and enemy of Osiris sometimes is represented as a dragon. In ancient Greece, a dragonish creature, Typhon, sent to upset the power of Zeus, was a creation of pure terror. Ovid (43 B.C.-17 A.D.) in The Metamorphoses described all the dragons as wearing crests on their heads – borrowed from Greek mythology. It is from 14th century England that the term wyvern comes, depicting these creatures as two-legged and two-winged, a word deriving from the Latin vipera (viper).

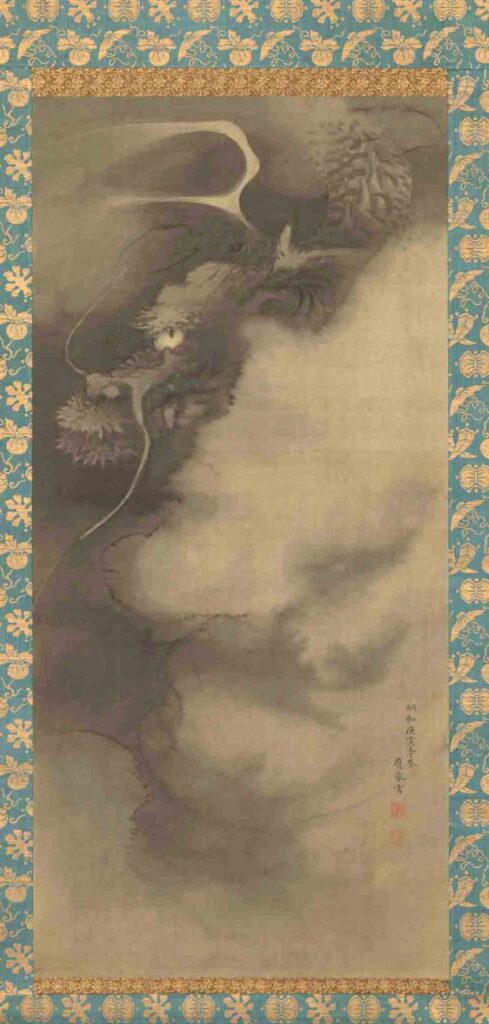

The Eastern benevolent dragons

The behavior of dragons from India, China, and Japan is almost exclusively benevolent. They are at one with nature; they are responsible for some natural phenomena, and some emperors derive their power from them. Their breath can change into clouds that can generate fire or rain.

They have a special link with water as they are always associated with this element. Some of these creatures are also water-deities, such as the Indian Nagas, gigantic with a serpentine form. Chinese dragons can sometimes be fish dragons, although they can also be of diverse varieties, such as Celestial Spirtual or Winged. However, they look scaly, with a head like a camel, horns like a deer, paws like a tiger, and claws like an eagle. In Japan, the dragon is more serpentine than the Chinese one; it is a sea-god and a river god, and human sacrifices were made for it.

Dragons in Western Middle Ages: The Monstrous Serpent of Hell

From the Middle Ages onwards, the role of the dragon changes and so does its representation. In Western culture, it becomes purely evil, hideous, and with the ability to spread disease and destruction. “The beast derived from Hell”, as the Old Testament and the Revelation of St. John show. It was a form of the devil, a symbol of desolation: the “Devil is like the Dragon” (Aberdeen Bestiary, f.66r).

As the Christian vision molds this negative image, the dragon becomes a threat to saints and represents a death sentence to people. They inhabit caves or water, and the air becomes turbulent when they fly. They can “squirt their sperm in wells” or rivers, predicting a terrible year (S.G. Bruce, The Penguin Book of Dragons, p. 99). Their enemies are elephants (which they suffocate with their tail), panthers and doves.

Red, long, winged: what does a dragon look like?

The main sources for iconography in the Middle Ages are bestiaries (12th – 13th centuries). The texts were those of ancient Latin and Greek authors, such as Isidore de Seville, Pliny the Elder, or the Physiologus. They were full of Christian symbolism, and dragons were under the snakes section.

In the Aberdeen Bestiary (13th century) and the MS. Ashmole 1511 (13th century) the neck is long as the tail – where the strength lies – it has one pair of wings and two paws. In other sources (British Library Ms. Harley 3244), it looks red, big and long, four-legged, and with two pairs of wings. It has “a crest – recalling the Devil’s crown – a small mouth, and narrow blow-holes through which it breathes and puts forth its tongue” (Aberdeen Bestiary, f.66r). Sometimes it has multiple heads or white and red striped skin (Bodleian Library, Ms. Tanner 184, f.65).

Saints versus dragons and dragons versus saints

The battle between dragon and saints dominated Christian literature for centuries, since the early times. By defeating evil, Saints free people from it. Saint Columba banished the aquatic dragon of the river Ness, converting pagans who assisted in the miracle. In the 11th century, a monk named Arnold encountered a dragon in Pannonia. It had a plumed head, the body covered with awful scales, and appeared suspended in the air, spreading coldness around. In the 12th century, God sent a fire-breathing dragon to punish the deacon of a church close to Winchester. He disrespected the relics of the Virgin Mary. Saint Margaret of Antioch (3rd-4th centuries AC.), as a consequence for refusing to marry the prefect Olybrius, underwent many trials and tortures. Hence, during one of the trials, Satan, disguised as a dragon, swallowed her. Its stomach rejected her, opened, and she managed to escape unhurt.

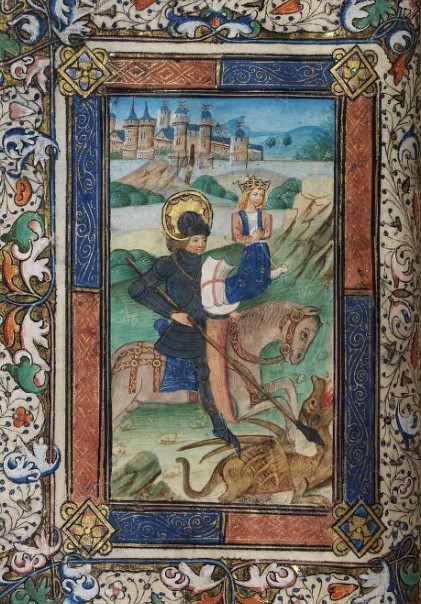

A special saint slayer

The legend of Saint George is widespread from the Jacob de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea (1265-66). George rescues Princess Sabra, slaying the dragon who menaced the nearby town with its deadly breath. In return, the king and his subjects converted to Christianity. This saint becomes very popular in the early Renaissance. His slaying of the dragon is frequent in art, and the monster looks different each time, depending on location and artist.

Generally, before the 15th century the monster has two paws or no paws and a pair of wings. In the De Grey Book of Hours (1400 – NLW MS 15537C) the monster looks green, four legged and with wings, spitting fire while it is being killed. A woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1501-1504) shows a dragon with the same characteristics. Miniatures with Saint Margaret from the 15th century show the same iconography. Many significant artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael, illustrated dragons in the Renaissance

G. Gagini, Relief of Saint George slaying the dragon, 1457, detail of the portal of Palazzo Quartara, Genoa.

Saint George slaying the dragon, The ‘De Grey’ Book of Hours (NLW MS 15537C), mid. 15th century, f. 31v, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – Image Courtesy of The National Library of Wales.

Contemporary dragons: literary models

In contemporary literature, dragons appear in fairy tales and fantasy novels. Among the most popular there are the ones of Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932) and E.E Nesbit (1858-1924). These two authors depicted dragons as misunderstood and unhappy creatures who would have been keen on being friends with humans.

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) has made a significant contribution to the modern image of dragons through his description of Smaug and dragons in his literature. However, their aspect is quadrupedal and mixed with Nordic mythology.

When dragons became animated

The world of animation has adopted dragons for quite some time, populating countless cartoons. Maleficient’s transformation (Sleeping Beauty, 1959) into an enormous and horrible beast is iconic: four legged, black and dark purple, spits green fire. More friendly and anthropomorphic dragons then start to appear, beginning with Pete’s Dragon (1977). Elliot is Green with pink hairs and his character resembles a whelp.

In the 90s these beasts became even more friendly and pleasant. Devon and Corwall (Quest for Camelot, 1998), a two-headed dragon, shows itself to be idiotic, incompetent, and even annoying. Mushu (Mulan 1998) has a specific behavior, as he is selfish and instinctive, but loyal and helpful in serving Mulan. In the series How to Train Your Dragon (2010- present), it is easy to grow fond of Toothless, the black dragon with yellow cattish eyes. He is intelligent, curious, and noble, and his presence makes him even a resource to Hiccup.

21st century dragons: a huge variety of beasts

In movies, TV series, or modern literature, dragons can take on a variety of characteristics. At the same time, more creatures presented in a novel or movie can be different. The role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons is one of the main references for the contemporary iconography of these beasts. In movies and TV series, they can be represented as 14th-century wyverns, as in Game of Thrones.

In Harry Potter, they are different from one another: some are more like Wyverns, and others are four-legged and with wings. For example, the Hibredean Black has black scales, an arrow-shaped tip at the end of its tail and purple eyes. On the other hand, the Norwegian Ridgeback (Norbert, Hagrid’s dragon) has black scales only on the back and his teeth are venomous.

@harrypotter it's norbert's year, i'm just here for the ride #harrypotter #yearofthedragon #movierecommendations ♬ original sound – Harry Potter

Looking at the authentic dragon

Nowadays, it is not unusual to hear nerdy debates on the right way to reproduce a real dragon in TV series or movies. What type of dragons have they put in Harry Potter? Why can Smaug in The Hobbit even speak fluently? As we have seen, according to the oldest sources, they had a plumed head, crests and not always paws or wings. The common element was the powerful tail.

Today’s fantasy world admits many different dragons. Everything is up to the author’s imagination. Everyone has his idea of how fantastic beasts could look. Thus, it is better to let all the dragons of mythology, literature, movies, and role games be as their authors want them, without prejudice based on crests, paws, colors, horns, tails, or wings.