Eggs have become an icon of Easter celebrations in the Western world. Painted and decorated, they represent the joy of spring and the rebirth of nature. But their history has its roots in more distant lands, as a symbol of the creation of the world. A concept that has evolved and adapted in different cultures, all the way to Christianity. Art is the most powerful medium through which stories interweave and propagate themselves, all the way to contemporary times.

The symbolic power of the egg in the myth of creation

The egg has been a recurring figure in the cosmogonic myths of ancient civilisations throughout the world. In Mesopotamian and Mediterranean cultures, the egg intertwines with the fertility goddess, symbolising the generative principle of life. In Greek myth, for example, the egg incarnates the embryo from which the entire universe was born. The Earth Goddess, Gaia, emerged from this egg, bringing with her the entire Olympian pantheon.

In Eastern cultures, often the cosmic egg has an association with the creation of the world and the birth of the gods. In Chinese myth, there is a legend about an egg from which emerged Yin and Yang, the fundamental principles of cosmic duality. According to ancient Egyptian civilisations, on the other hand, the sun god Ra, in some versions of the myth, emerged from an egg laid in the primordial ocean. Also for Native Americans, such as the Navajo, the egg represents the source of life and the creative force of the cosmos.

An offering for the afterlife: Eggs as symbols of rebirth and immortality

Eggs were often funerary objects in various ancient cultures, symbolising rebirth and life after death. In ancient Egypt, eggs were sometimes laid in tombs as offerings to grant the body life in the afterlife. The same happened in some Asian and Mediterranean cultures. This use of eggs reflected the universal conception of life as an endless cycle that goes beyond death.

This terracotta vase (c. 400 BC) is a typical funerary vase whose shape resembles an egg. Found in a tomb near Athens, it depicts the abduction of a woman, often identified as Helen of Troy.

Leda and the swan: the birth of Castor and Pollux, Clytemnestra and Helen

According to Greek mythology, Leda, queen of Sparta, laid eggs from which two pairs of twins were born. From one egg came the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, and from the other Clytemnestra and Helen. This birth occurred after Zeus, as a swan, joined Leda, who on the same night also joined her husband, Tindarus. In the most common versions of the story, only Helen and Pollux are children of Zeus. There are several versions of the myth of Leda and the Swan, but what is certain is that it symbolises the mingling of the divine and the human. The descendants of this union play prominent roles in Greek mythological narrative, embodying values of courage, beauty and fate.

Sacred Art: From Medieval Symbols to a Renaissance Vision

Hildegard of Bingen and her mystical visions

In the Christian context, the egg has taken on different shades of meaning. During the Middle Ages, the egg represents the empty tomb of Christ, indicating the resurrection and eternal life. This concept relates to the practice of giving eggs as gifts during Easter, celebrating Christ’s victory over death. One of the most important figures in Christian theology was the German nun and mystic Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179). She transfigured the concept of the cosmic egg in one of her most famous writings, the Scivias, from the Latin Sci vias Domini, meaning know the ways of the Lord.

In the manuscript’s preface, the nun explains how she was induced by God to write about the 26 visions she had during her mystical experiences. In the third vision, entitled God, Cosmos and Humanity, she also adds to the explanation a drawing of the universe as an egg. According to the nun, man and the cosmos are both composed of the four elements. Air, earth, fire and water are thus placed at the basis of the generation of the whole, hence the reference to the egg, which embodies fertility.

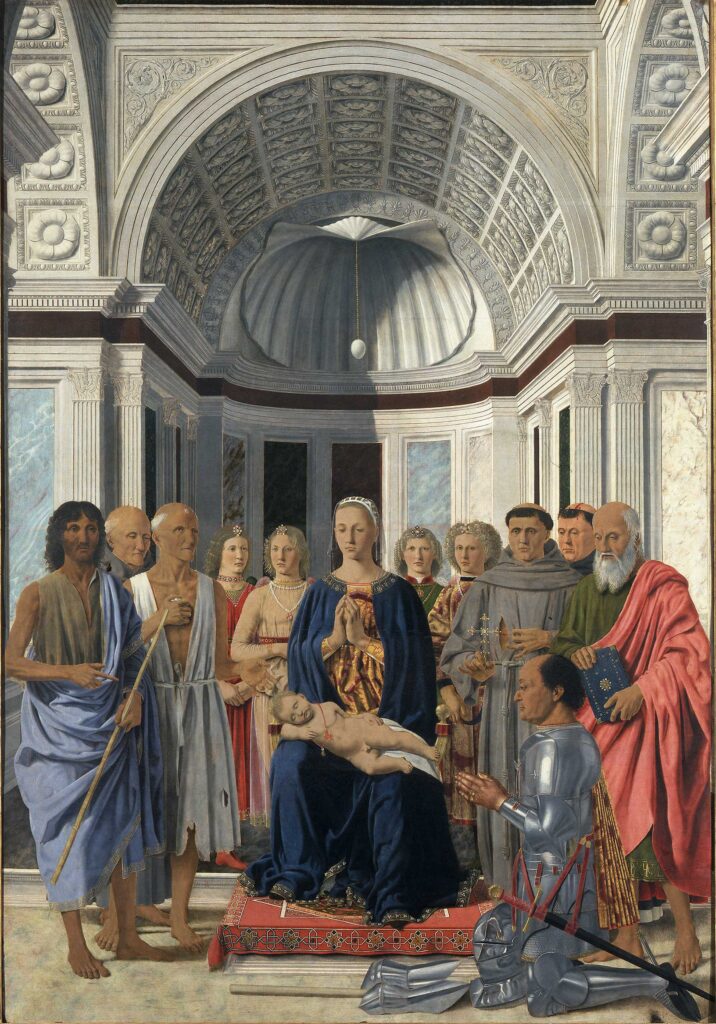

Piero della Francesca

The Montefeltro Altarpiece is a Renaissance work that Piero della Francesca created between 1472 and 1474 and is also known as the Madonna della Misericordia. This masterpiece lies in the church of San Bernardino in Urbino. It was commissioned by the painter Federico da Montefeltro, thought to be for funerary purposes. The painting features the image of an egg as well.

The light, one of the characteristics of Piero della Francesca’s art, delicately and uniformly illuminates the figures. This gives them an apparent three-dimensionality and creates a mystical and sacred atmosphere. The delicate tones and soft colours convey a sense of serenity and transcendence.

The work is significant for its symbolic and allegorical value. It represents the divine protection and mercy of the Madonna towards the Montefeltro family, who dominated Urbino during the Renaissance. The presence of saints, including St. John the Baptist and St. Jerome, surrounding the Virgin from the left, emphasises the religiousness and devotion of the family. The sleeping child alludes to motherhood and death at the same time. This element reinforces the hypothesis that the work was for the family tomb.

The Herald of Faith: why the egg does not cast a shadow?

The ostrich egg, located in the upper part of the painting, has very strong symbolism on several fronts. The ostrich was in fact the heraldic emblem of the Montefeltro family. Its position indicates faith is always placed above reason. The shell from which it hangs recalls the myth of Venus, as painted for example by Botticelli. In the Christian reinterpretation, in this case, she embodies the Virgin, at the centre of the work. It is no coincidence that by referring to Mary, the egg is also a symbol of purity. A peculiarity is that although the light falls directly on it, the egg does not cast a shadow.

The egg dance: spring within a game

Transcending the cultural boundaries of ancient civilisations, nature has always expressed its sense of rebirth through spring. It is still celebrated today on the day of the equinox. The term, derived from the Latin ‘aequa nox‘, refers to the moment when day and night are the same length. During the Renaissance, it was customary to celebrate this day with the egg dance. The dance, of Saxon origin (5th century Germany), involved an intricate play of movements. Regardless of the specific version, the aim was always the same: not to break the eggs by moving them or covering them with a bowl, using only the feet.

This tradition spread in many variants in different parts of Europe and, although it may seem to be a popular practice, there are testimonies that indicate its practice even among the nobility as a pre-wedding dance. The painting by the Dutch painter Pieter Aertsen depicts this playful moment taking place inside a brothel.

History of a lucky ritual

An article in the American Magazine of 1895 reported on this custom during the wedding of Margaret of Austria and Philibert of Savoy, which took place on Easter Monday 1498. It was thanks to this event that the egg dance became an Easter tradition. In pre-wedding tradition, the betrothed couple had to dance on ground covered with eggs and only if they managed not to break a single one would their marriage be lucky. Margaret and Philibert were an exception, as although they completed the dance, the Duchess became widowed three years after the wedding.

Ukrainian pysanky and the legendary Fabergé eggs

The Ukrainian tradition of decorating pysanky eggs dates back about 2000 years. These works of art come to life by using a wax and dye technique. In the beginning, pysanky had ritual and symbolic meanings, linked to fertility, protection and rebirth. Over time, they became distinctive artistic expressions of Ukrainian culture. Each design and colour tells a unique story, passing on traditions and beliefs through generations. Today, pysanky receives appreciation worldwide for its intricate beauty and its connection to Ukrainian history and culture, which is why there is a dedicated museum in the city of Kolomyia. The Pysanka Museum, not by chance in the shape of an egg, was built in 1987 and to date contains more than 10,000 decorated eggs from not only Eastern Europe but from all over the world.

The golden hands of Fabergé

Again in Eastern Europe, this time in Russia, the egg becomes a precious jewel in the hands of an incredible goldsmith. Fabergé eggs are world-famous jewels, symbols of luxury and craftsmanship. Their story begins in the 19th century, with Russian jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé. Tsar Alexander III asked him to create an Easter gift for his wife, Empress Maria Feodorovna. This first egg aroused so much interest that Fabergé continued to create one each year for the Tsar. Later, other aristocratic families also began to commission them. Each egg was unique, with elaborate designs and intricate surprises inside, such as miniatures of palaces, carriages and animals.

Fabergé egg production continued until 1917 when the Russian Revolution ended the monarchy. Many of the eggs were dispersed or sold during that tumultuous period. However, their charm and artistic value remained intact over time.

Today, Fabergé eggs have become treasures of jewellery art and are exhibited in museums and private collections all over the world. Each piece represents not only excellent craftsmanship but also a chapter in Russian imperial history and 19th-century decorative art. This is an egg that Tsar Nicholas II gave to his wife Aleksandra on the occasion of Easter in 1907.

The ‘Easter Egg’ and its evolution in popular culture

The term ‘easter egg‘ was coined in computer science in 1979 by one of the developers of Atari Inc., the US company that created the first action-adventure video game Adventure. Warren Robinett, the game’s creator, hid his signature in the video game to free himself from the anonymity imposed by the company. The director of software development, Steve Wright, appreciated Robinett’s creativity and therefore proposed to include a surprise to be found in each video game that would further stimulate users’ interest.

The decision to call these surprises ‘easter eggs’ descended from the traditional Easter eggs that used to be hidden in England during a children’s treasure hunt. These surprises in the software were not documented and were not part of the core functionality of the programme. Over time, they became an artistic signature for the developers, adding a touch of fun and mystery to their creations. Often secrets came up only through specific actions or key combinations.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s secrets

Although the term easter egg was thus defined only a few decades ago, there are many hidden references in the art world, such as self-portraits and secret symbolism that only surfaced after years, if not centuries, of study. Leonardo da Vinci is the master of coded messages, his art conceals many mysteries that are still waiting to emerge. For example, according to many critics, in the Adoration of the Magi, a work left unfinished, Leonardo hides a youthful self-portrait of himself in the child on the right margin of the work. Returning to the Easter theme, there are two trees that are part of the painting, a laurel tree as a symbol of the resurrection and a palm tree to indicate the passion of Christ.

A game of hide-and-seek with Disney

The concept of the easter egg has also evolved in the film industry, in particular in sagas such as the Marvel sagas, and in the productions of animation Colossus, Disney. In many films, there are homages, even artistic ones, quotations and cameos that only the most scrupulous observers have been able to recognise. For instance, in The Little Mermaid (1989), a painting now exhibited in the Louvre appears, namely Madeleine à la veilleuse (1644 c), by Georges de La Tour.

Some of the most known self-celebrations are the cups from Beauty and the Beast (1991) in Tarzan (1999), or Rapunzel (2010) attending Anna‘s wedding in the first chapter of the Frozen saga (2013); in a nutshell, a way for Disney to thank its followers by self-celebrating its greatest successes.

Art has always had the ability to decline in different forms: today, the Easter egg has also taken on commercial meanings, becoming a symbol of the Easter festivities, in particular for children who can’t wait to unwrap their Easter eggs and find a surprise in them. However, it still retains a deep symbolic meaning of rebirth, hope and new life, linking ancient traditions with the contemporary.