Every book changes the way I work. I wouldn’t start a book without the belief that it is going to change everything for me

Manuele Fior

One could say that cartoonist and artist Manuele Fior is mostly defined by his style changes, work after work. And yet, he always includes recurring features: semi-biographical events; the theme of travelling and starting a life somewhere new; the clear influences and quotes of renowned artists. Looking into his four major and most recent works will show how much every new graphic novel, for Fior, is both an exploration of the unknown and a further analysis of recurrent themes.

The exhibition dedicated to Fior in Pisa, Italy, entitled Manuele Fior – Viaggio a colori (Manuele Fior – A colored journey), focused on how eclectic his work was. Hosted from the 20th of April to the 1st of September 2024 at the Palazzo Blu museum, it celebrated Fior’s last fifteen years of work, showing how much the different uses of color in his works changed and influenced each story.

From 5.000 km per second (2010) to Hypericum (2022), passing through The interview (2013) and Celestia (2 vols 2019-2020) everything continuously transforms: not just the colors, but also the drawing style, the genres, the story structure.

Manuele Fior: a travelling artist

Manuele Fior has travelled as much as his characters. Born in Cesena in 1975, his family frequently moved due to his father’s job, as an air force pilot. After studying architecture in Venice, he started to work as an architect in Berlin in 1998. He then lived in Egypt, Oslo, dropped his job to become a full-time cartoonist, stayed in Paris for some years and finally returned to Venice, where he now lives.

Also, his path to comics was not a linear one. A passionate illustrator since when he was a kid, he grew up with Japanese animation and Marvel comics, but then put aside the idea of becoming a cartoonist to focus on university. Moreover, in the 1990s, the comic publishing industry wasn’t very solid and encouraging, especially for beginners. And yet, while Fior was working in Berlin, he managed to publish some short comic stories. Meanwhile in Italy, as the new millennium started, the comic sector was recovering, also thanks to comics fairs like Lucca Comics and Napoli Comicon and new-born publishing houses. And one of them, Coconino Press (founded by Igort in 2000), published Manuele Fior’s first graphic novel, Red Ultramarine (2006), which earned him the Attilio Micheluzzi Award as best illustrator in 2007.

Fior’s career as an artist has always been two-sided, as he always worked as a cartoonist and as an illustrator: in both cases with great success, as he is sought after by magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair and some leading Italian newspapers. On the other hand, comics-wise, success came in 2010, thanks to his graphic novel 5000 km per second.

5000 km per second: the image before the words

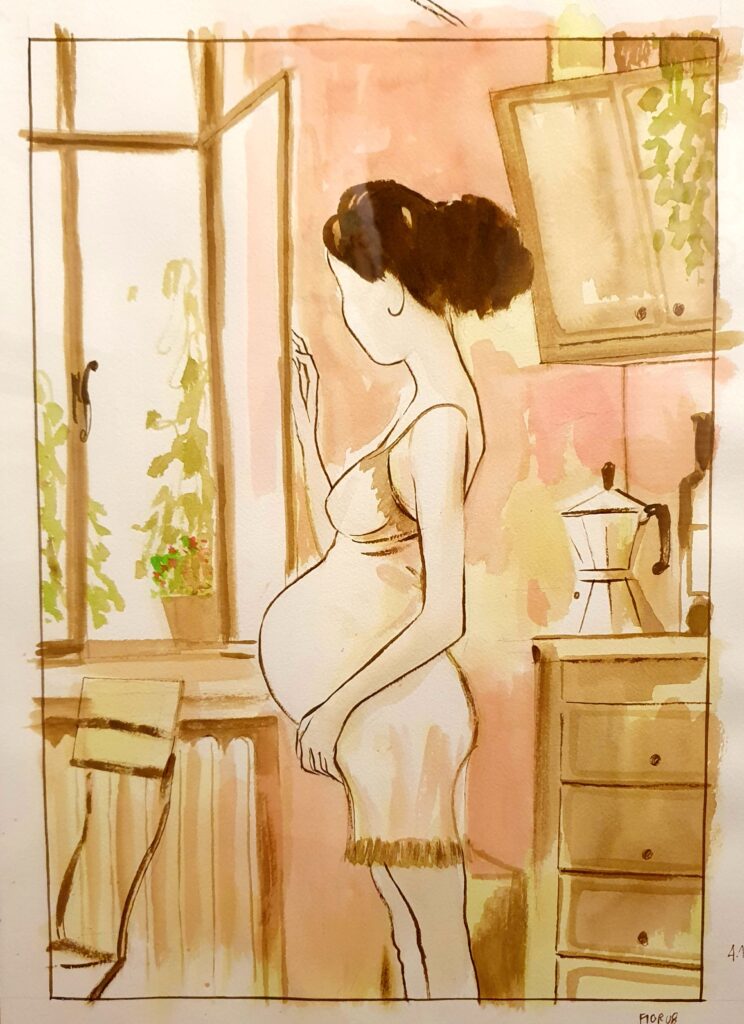

Fior’s storytelling relies a lot on visuals, much more than on dialogues and plots. For him, the better part of the story is told by drawings, by the use of color, by the panel composition. In doing so, Fior often makes more or less explicit references to celebrated artists, from painters to architects, from cartoonists to movie directors. In 5000 km per second one can find similarities with Herni Matisse’s and Amedeo Modigliani’s way of drawing faces, while the use of color partially recalls Gauguin’s post-impressionistic use of pure colors.

The point of Fior’s graphic novels is not much about thrilling stories revolving around shocking plot points, as it is about communicating the subtleties of a character or conveying a feeling through coloring and drawing style.

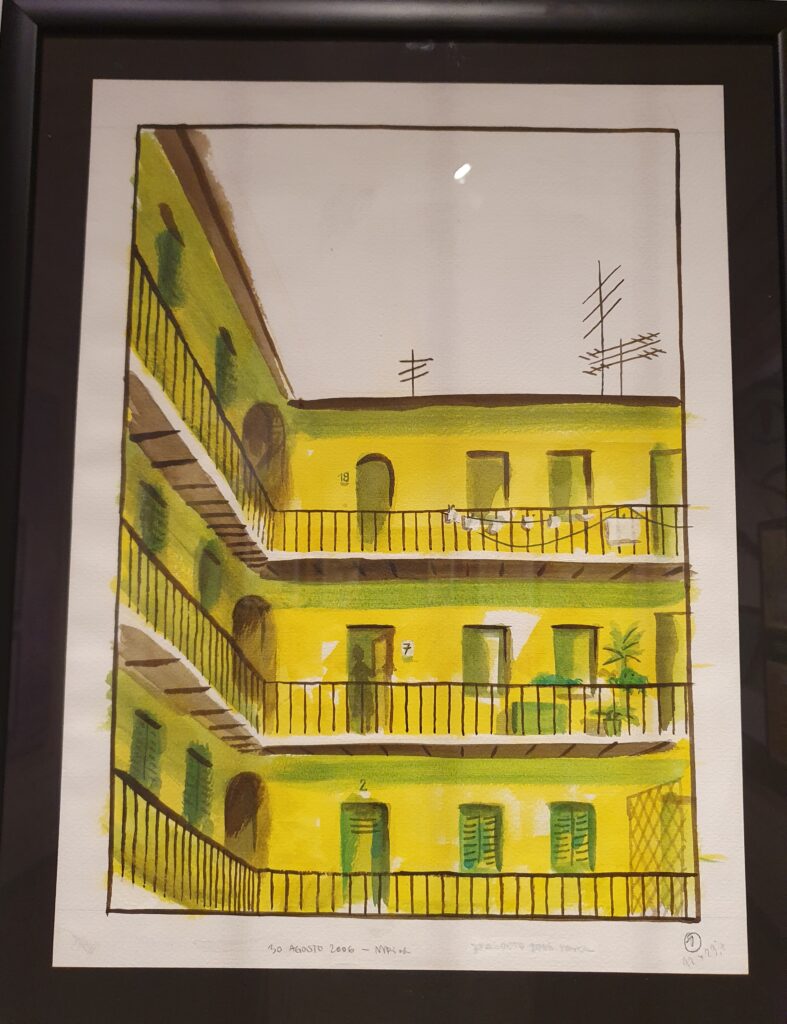

5000 km per second is a clear example of all this. The story follows the three protagonists, Piero, Lucia and Nicola, through decades, with brief chapters showing major changes in their lives. From chapter to chapter, color sets the mood more than anything: from the bright yellow and green of the first part, filled with the expectations and the energy of adolescence, to the dim purple which dominates the ending of the story, filled with the bitter-sweet acknowledgment of a mostly bygone life.

Auto-biography and comics

Most of Fior’s characters are shown in the act of leaving the place where they used to live. In 5000 km per second Lucia just moved when the story starts, she will then move to Norway to write her dissertation and finally come back to Italy years later. Piero, on the other hand, becomes an archeologist and he’s always between Italy and Egypt due to his job.

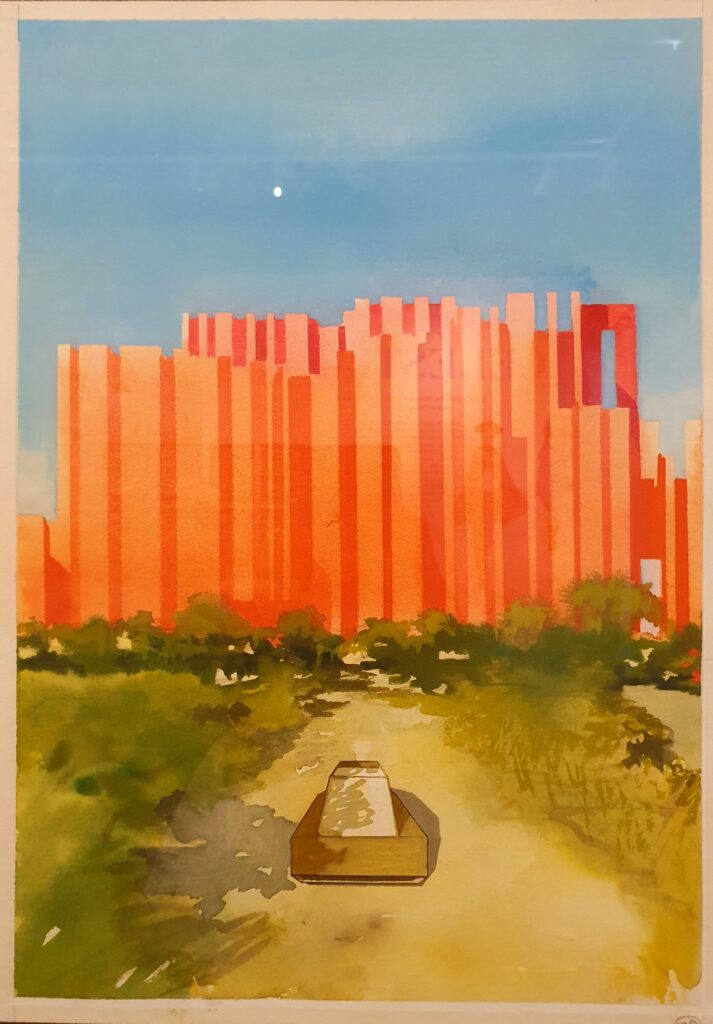

Of course undertaking a journey, actual or metaphorical, is what almost every character does in any story. However, in Fior’s works, what triggers the event is often intertwined with the necessity to move to a different town or place (be it for work, for studying or just out of the will to explore different contexts). Aside from recalling Fior’s experience of having lived in several cities, it is also a way to express the necessity of finding one’s place in the world. A striking example of this is the scene where Piero gets lost in a dream, driving around an immense building which recalls Giorgio De Chirico’s metaphysical paintings.

Fior here portrays life as endless wandering, which is highly demanding and in the end finds people mourning all sorts of lost opportunities.

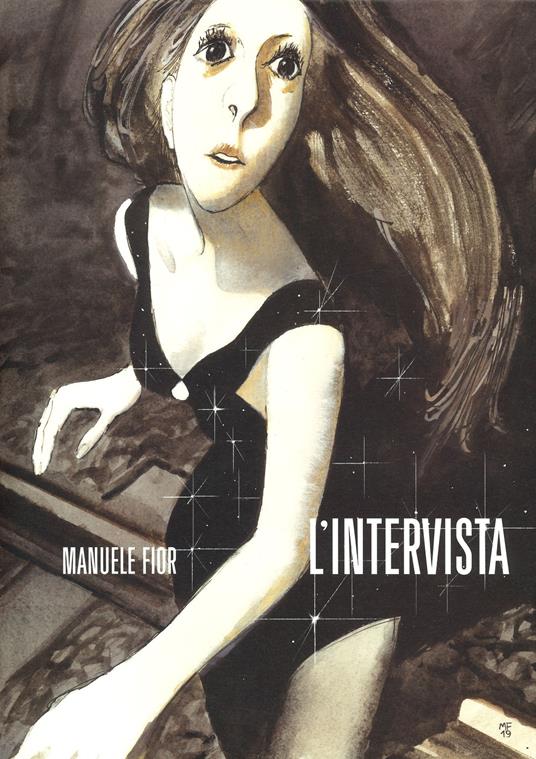

The interview: a realistic science-fiction

Color marks the shift from 5000 km per second to The interview as well, as Fior decided to lose acrylics in favor of Indian ink and charcoal. A choice bound to create a sense of hanging and an eerie atmosphere, according to Fior inspired by Michelangelo Antonioni’s movies.

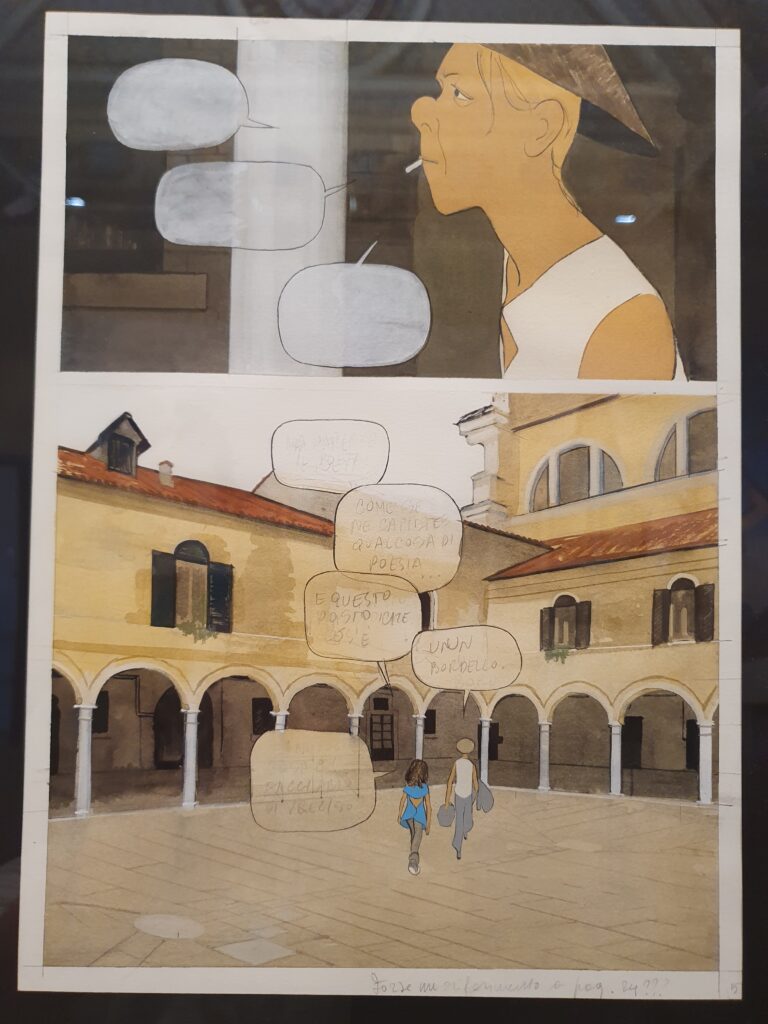

The evident change on the panel suggests also a change in themes and genre. The story is set in Udine, in 2048, a future not very much different from the present, except for self-driving cars and some eccentric dress. Raniero is a psychologist going through a separation with his wife, who wants to move out and leave him. Dora is one of Raniero’s patients, she can communicate telepathically and is a member of the New Convention, a group which practices non-monogamous relationships. In the background, extra-terrestrial beings are approaching Earth and they will change forever how people relate to each other.

The use of charcoal and of the black and white enhances the sense of distance between the reader and the events of the story, while making alien encounters more surreal and mysterious. However, Fior builds a convincing futuristic setting also thanks to a mindful use of architecture, which here gains more relevance than in 5000 km per second.

When you put one of Louis Kahn’s buildings in a science fiction story like mine, this building is perceived as a futuristic one even though it was actually built in the 60s! Modern architecture possesses a kind of visionary inertia.

Manuele Fior

Louis Kahn’s National Assembly Building of Bangladesh is where takes place the last scene of the interview. While Raniero’s house is an exact reproduction of one of the Usonian houses by architect Frank Lloyd Wright, characterized by a sharp and elegant design.

Despite the surreal or futuristic elements, though, the better part of the graphic novel gives the feeling of an everyday life context, more than a science fictional one. Raniero and Dora’s relationship is a way to explore similarities and differences between their respective generations. Even telepathy is not much of a superpower or a scary ability, but mostly the symbol of how younger and older generations communicate in utterly different ways.

Celestia between fantasy…

My main influences were The World of Edena by Moebius, or Little Nemo by Winsor McCay. The kind of stories where there is no greater plan and everything is added a little at a time

Manuele Fior

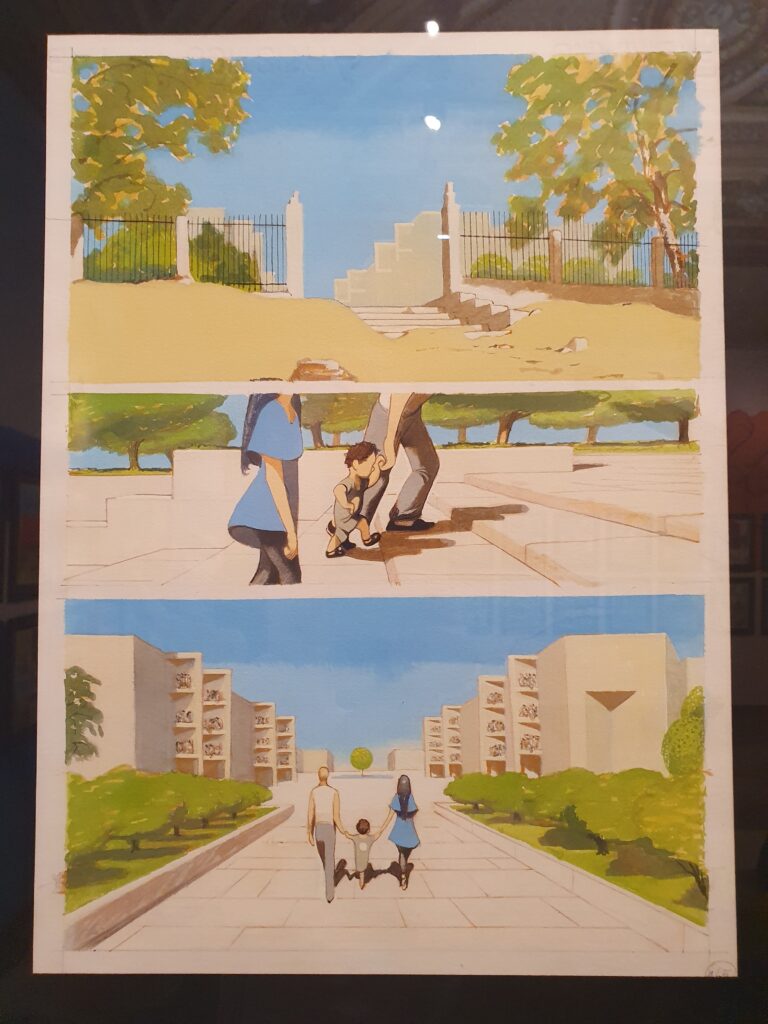

Manuele Fior keeps on playing out an unreal setting in his following work, Celestia. The whole world was brought down by an unspecified Great Invasion: some people found shelter on a small island, Celestia, an imaginary Venice completely separated from the Italian peninsula. Nevertheless, people keep on living as they can.

Fior reconnects to the origin of comics, both for genre and narrative structure. Celestia’s setting, with fantasy and science-fiction elements, is a reference to the most common comics genres, especially in the early years of the medium, as shown by comics like Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905) or Flash Gordon (1934). And the graphic novel also recalls the episodic storytelling of those times, when comics were published on the comic strip page in the newspapers and the characters explored, step by step, a different aspect of the narrative world without a defined plot.

…avant-garde and architecture

Fior followed his characters, Dora (once again a girl gifted with telepathy) and Pierrot (capable of telepathy as well), without a clear outline from the start of what will happen next. In doing so, he hints also at the ideas of Moebius (Arzak, The Incal) and of his comics magazine Métal Hurlant, which wanted to explore the potential of comics in terms of panelling, drawings and alternative forms of storytelling: comics intended not just as a well-crafted entertainment, but as a multi-faceted artistic expression. In Celestia Fior paints using gouache and Indian ink, reaching the peak of his production in the application of color and dynamism of the panels.

Counting on the strength of his illustrations, he is much more interested in showing Celestia’s places to the reader, instead of verbally unravelling the history of this imaginary world. Once again Fior’s knowledge of architecture comes in handy. Several scenes take place in Ricardo Bofill’s buildings of the tourist complex La Manzanera, located in Alicante or in Louis Kahn’s (him again) Salk Institute for Biological Studies in California. The peculiar design of these buildings, transported into Fior’s comics, immediately creates a solid impression of Celestia’s world, a world where hundreds of stories could be told, aside from Fior’s.

From 2001: A Spacey Odissey to Mark Rothko

However, Fior doesn’t neglect characters and plot in favor of illustrations. While he walks the reader into Celestia’s world making Pierrot and Dora explore its marvels, he also keeps track of themes like communication and the constant travelling. Actually, travelling and bonding with others in Celestia deeply intertwine. Pierrot lives isolated in Celestia, making a living day by day: scarred by his mother’s death, he protects himself behind a wall of caustic irony. Casually finding himself leaving Celestia and travelling with Dora is what will help him heal this wound and find a way to reconnect with others. Seeing what is out of Celestia and meeting the people living in the world after the Great Invasion is what will give Dora and Pierrot the tools to face the challenge and the issues they left behind in Celestia.

Apart from the exploration of unique places and buildings, travelling is an inner experience. Telepathy can be painful, like an oversharing of feelings where two minds end up clashing. But it can be also a tool to exploring and understanding one’s feelings. In one of the most striking sequences of the graphic novel, Pierrot gets in touch with the deep sorrow for his mother’s death. Mixing Mark Rothko’s paintings and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (the scene where David Bowman flies into the colored light vortex inside the huge monolith), it’s like Fior makes Pierrot fall inside the pit of his emotions, to finally find a way to climb out of his pain. It’s just after that that he manages to telepathically let Dora experience the tragic memory of his mother’s death.

Heading forward, looking backwards: Hypericum

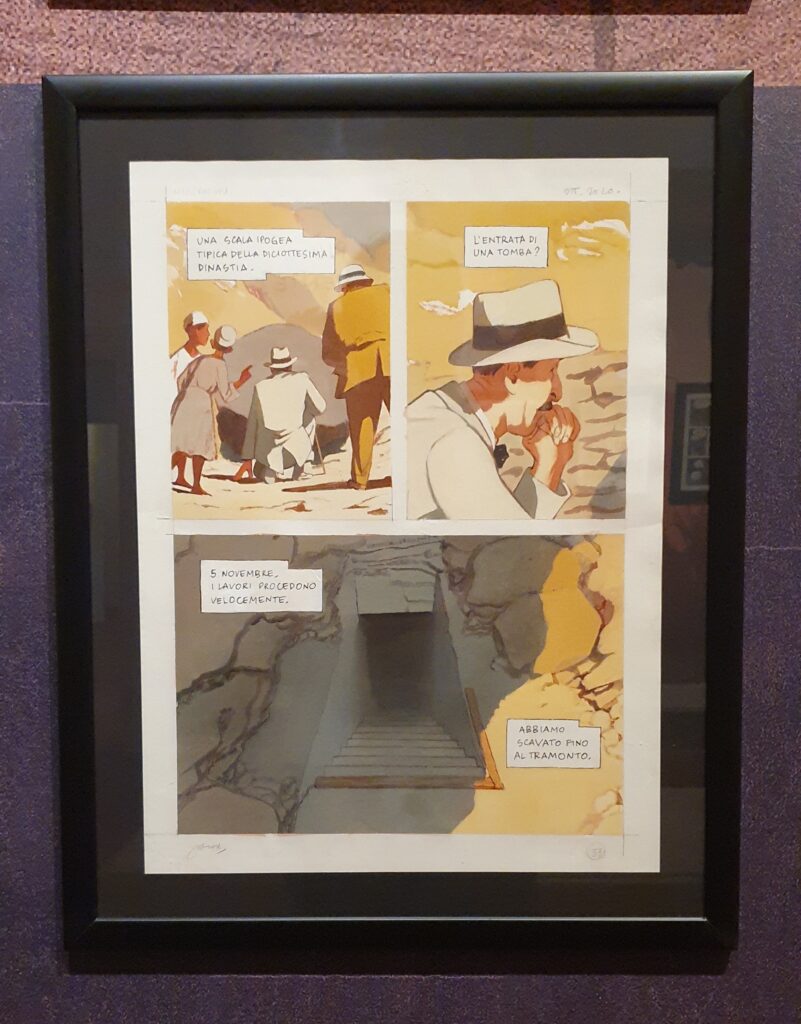

After two graphic novels oriented towards fantasy and science-fiction, Fior goes back to a story grounded in the real world and rich in auto-biographical elements. In Hypericum Teresa, an archaelogy scholar, moves to Berlin to participate in the curation of an exhibition about Tutankhamen. Simultaneously, Fior narrates the finding of Tutankhamen’s tomb by Howard Carter in 1922, using the words of the archeologist’s diary.

To create Hypericum, Fior makes for the first time a storyboard of the whole story, before starting to draw and write it. A choice that emerges from the smooth and convincing development of both characters and story, aside from the clear ability of an experienced narrator.

Once again the protagonist of the story finds in the necessity to live in a different city a way to find a direction for her life, somehow recalling 5000 km per second. However, here the narration is less syncopated: the reader follows more closely the development of Teresa’s love story with a young man she meets in Berlin, Ruben, along with her choices academia-wise.

For once, the storytelling relies more on the plot and on dialogues, distancing itself from a graphic novel like Celesta. And yet, narration by images remains dominant in the turning points of the story, like in the beginning where Fior introduces both Teresa and Carter, in the scenes where Carter explores the tomb or, in the end, when the attack on the Twin Towers marks the closure of a horizon of hope and optimism for Teresa and Ruben’s generation.

Hypericum is like a summary of what Fior did and can do, both as a narrator and as a painter. And even if the story begins and ends with a clear scheme where every piece falls in its place, this last work of his leaves the reader wondering what Manuele Fior will do next.