On October 2, 1968, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, one of the artists who revolutionized 20th-century art passed away: Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp’s genius lay in shifting the focus from making to conceiving art.

Not by chance, his most famous works are not paintings, but objects, acts, even choices. If, when facing a painting, a sculpture, or an ordinary object, we ask ourselves the question “is it art?” we owe it, at least in part, to him.

Duchamp is truly a tutelary figure for those who deal with contemporaneity. Through his work, he managed to dismantle the traditional art concept, paving the way for the conceptual languages of the 20th century.

Paris 1904, the Birth of the Avant-Garde

Duchamp was born in 1889 in Normandy, in Blainville-Crevon, into a bourgeois family of artists. Two of his brothers, Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon, would also become protagonists of the avant-garde.

He grew up in a cultured environment open to experimentation. He soon expressed the desire to move to the capital, where he arrived in 1904. That year, Paris was buzzing with energy. Studios, galleries, and cafés served as the meeting grounds for painters, sculptors, writers, and musicians. The ground was fertile for the 19th century to give way to the avant-garde of the 20th.

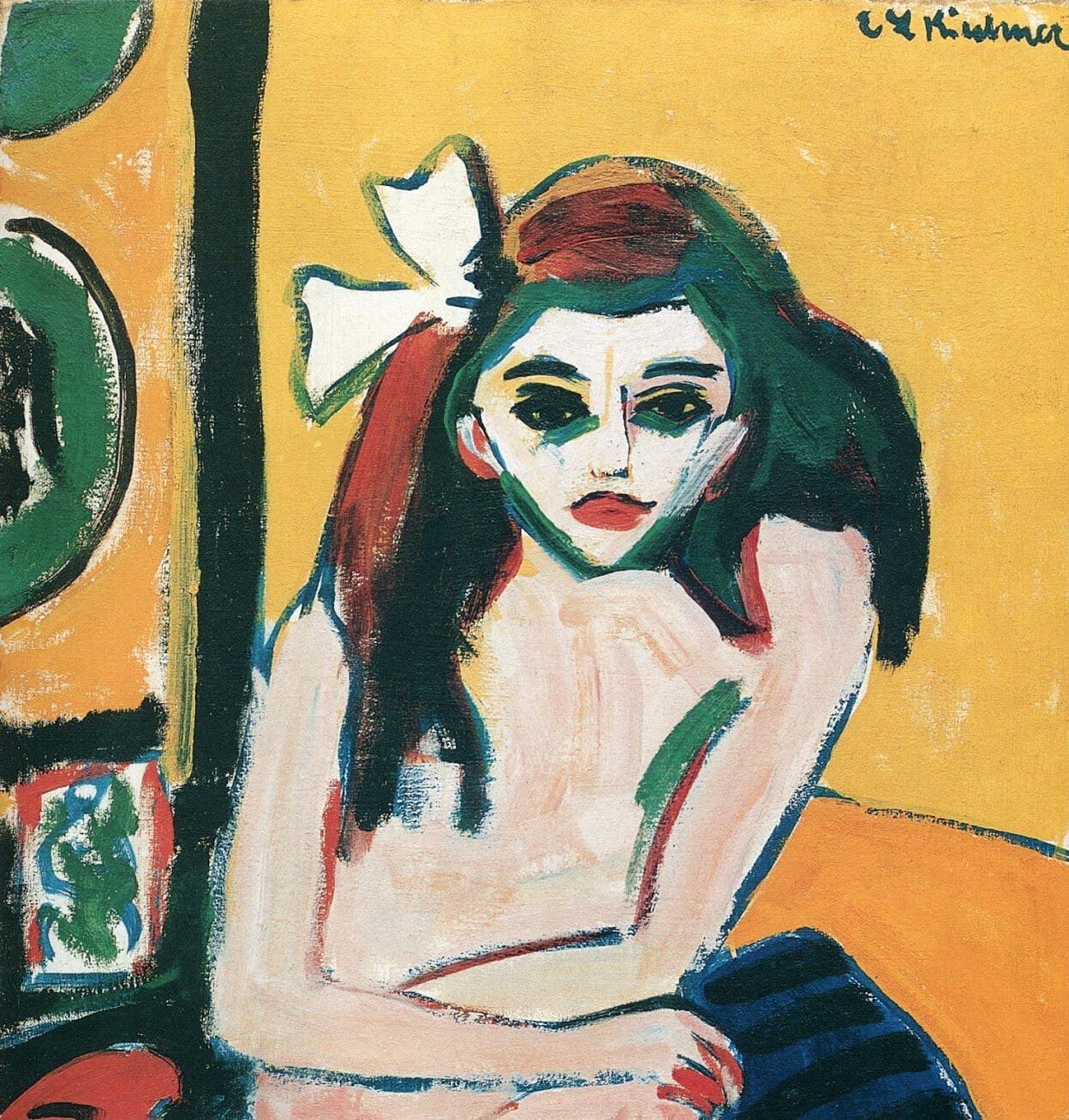

The year 1904, in this sense, is a symbolic one. In 1904, Henri Matisse painted Luxe, calme et volupté. A manifesto-work, exhibited at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, which gave birth to the Fauvist movement. The name (fauves = “wild beasts”) was coined ironically by a critic, struck by the free, subjective, at times violent use of color. In Fauvist paintings, pure and intense hues no longer described reality but reflected the artist’s emotions in front of it. In short, in 1904, the chromatic revolution was being prepared, which would explode the following year.

In 1904, moreover, Pablo Picasso settled in Paris for good, opening a studio in Montmartre. The artist was in transition from his Blue Period to his Rose Period. He, too, used colorin a subjective way, depicting circus themes and light figures. A prelude to Cubism.

Nude Descending a Staircase: Duchamp’s Beginnings

Marcel Duchamp could not help but be influenced by this ferment permeating Paris in the early 20th century. His first works were indeed inspired by Cubism and Fauvism. However, by 1912, his career had already taken a more original turn. That year, Paris hosted an exhibition destined to make history. For the first time, the works of Italian Futurist painters were shown in the capital. Over thirty works by Boccioni, Severini, Russolo, and Carrà opened up a previously unknown scenario in Paris.

The exaltation of speed, dynamism, and modernity—contrasting with traditional art—and the representation of movement and simultaneity through force lines and fragmented forms struck a chord with Duchamp. In 1912, the painter presented Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2. Here, he combined Futurist dynamism and Cubist fragmentation, causing a scandal. The work, which depicted a human figure in motion as if it were a cinematic sequence, was rejected for being too “mechanical” and “offensive”. The young artist thus realized that his path would conflict with traditional artistic institutions.

The Conceptual Turn: When a Urinal Becomes Art

Duchamp’s Parisian career was soon destined to be interrupted. The outbreak of the First World War compelled him to emigrate to the United States in 1915. In New York, two years after his arrival, Duchamp performed one of the most radical and provocative gestures in the history of contemporary art.

Walking into a plumbing supply store, he purchased an ordinary white porcelain urinal. He turned it upside down, signed it with the pseudonym “R. Mutt,” and presented it, under the title Fountain, at the annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. The association proclaimed it would accept any work upon payment of the membership fee. No jury, no selection. But faced with this everyday object, simply removed from context and redefined as sculpture, the committee members—of which Duchamp himself was part—decided not to display it.

That paradoxical, sensational refusal became the trigger for a revolution. Duchamp had not made a work in the traditional sense, but had chosen an object and proposed it as art. Duchamp’s gesture gave rise to a series of questions destined to change the art world forever: Who decides what is art? Is an artist’s signature enough to make an ordinary object art? Is transforming a urinal into a fountain—thus changing the meaning of something—an artistic gesture? Does the very fact that the urinal raises such questions make it worthy of interest?

When ordinary objects become art | The ready-made

Thus was born the concept of the ready-made. Everyday objects, which, isolated and placed in an exhibition context, become vehicles of an idea rather than of technical skill. With Fountain, attention shifted from craftsmanship to choice and concept.

The original urinal, which was probably destroyed, has not survived to this day. However, the work lives on through photographs, accounts, and replicas authorized by Duchamp himself in later years, such as the one at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Today, Fountain is considered a symbol of the break with 19th-century aesthetics and one of the cornerstones of conceptual art. With that object, Duchamp demonstrated that art could be above all a mental act. Fountain shifted attention from aesthetic value to conceptual value. It does not matter how an object is made, but what its selection means.

The Mona Lisa with a Mustache: Desecrating Untouchable Masterpieces

After desecrating and surpassing the artistic tradition with a simple urinal, Duchamp continued his revolution. If any everyday object could be art, then what sense does it make to celebrate, with almost religious spirit, the masterpieces of the past? They are and remain masterpieces, but who said they cannot be rethought, deconstructed, defaced?

And so, why not take the absolute myth, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and desecrate it? L.H.O.O.Q. (1919, New York, private collection) is a postcard of the Mona Lisa to which Duchamp added a mustache and goatee, accompanied by a title that, when read in French, sounds like elle a chaud au cul (“she has a hot ass”).

An ironic and provocative gesture itself becomes a work of art. It is an act that anticipates the strategies of Pop Art and Postmodernism, where images are quoted, multiplied, and manipulated.

Duchamp’s legacy, from Andy Warhol to Banksy

Duchamp did not just provoke or create strange objects. He forever changed the very meaning of art and the questions an artwork poses to us. Before Duchamp, it was enough to stand before a painting or sculpture and admire its beauty or technical mastery. After Duchamp, reflection became more complex. Art became an idea, a process, a context.

Artists such as Andy Warhol, Piero Manzoni, Joseph Beuys, Maurizio Cattelan, or Banksy owe to him the possibility of transforming actions, objects, and everyday images into works loaded with meaning. Even the gesture of signing or reinterpreting an iconic object—from Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup to Banksy’s Madonna with a pistol—has Duchampian roots.

More than a century after his ready-mades, Duchamp remains a point of reference for those who see in art not only aesthetics, but critical thinking, irony, and freedom. In this sense, he is the true artist of the future: the one who taught us that sometimes, choosing is already an act of artistic creation.