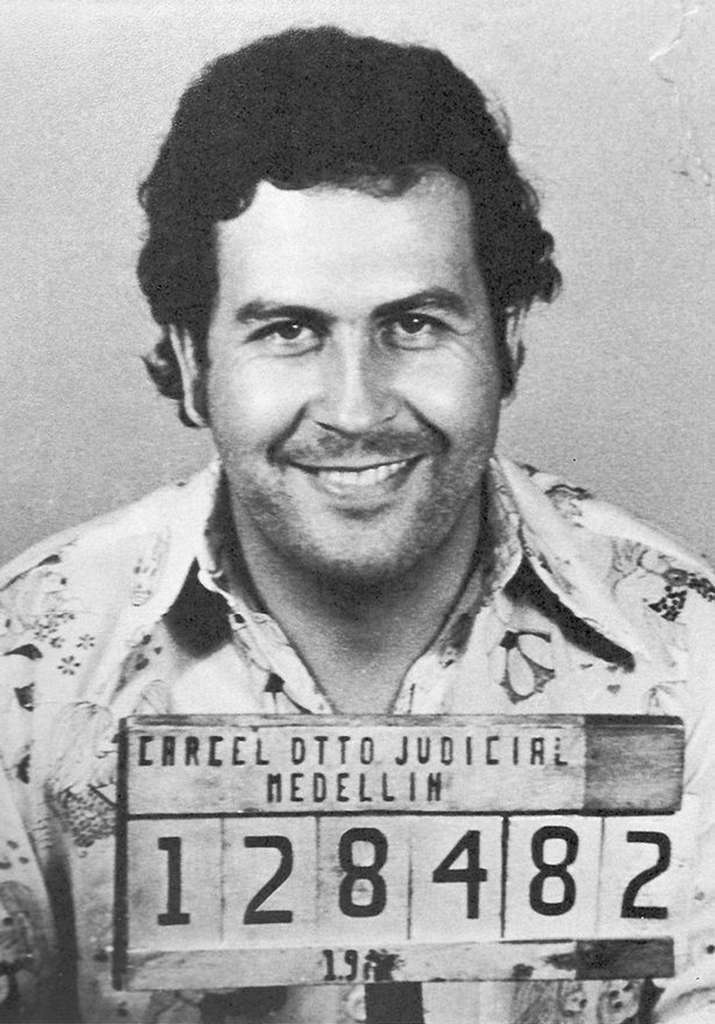

Pablo Escobar, the “cocaine king,” is one of the most controversial figures in contemporary culture. His life was marked by power, violence, and ruthlessness. However, today, his name is also linked to a broader phenomenon: myth. His story has become a global symbol, absorbed by popular culture, the media, and crime tourism.

Active from the 1970s to the early 1990s, Escobar dominated the international cocaine trade. Born into a modest background in a small town near Medellín, he became involved in crime at a young age, exploiting institutional corruption and violence to expand his influence. With boldness, he recognized the growing demand for narcotics in the United States and used it to his advantage.

In the 1980s, he founded the fearsome Medellín Cartel, which dominated the cocaine market and reportedly controlled about 80 percent of the supplies to the U.S. His fortune exploded, making him one of the world’s richest and most powerful men. Meanwhile, the cartel began to exert enormous influence over Colombian politics and law enforcement, further consolidating its power. His reign went beyond drug trafficking, influencing Colombian politics, media, and the armed forces. Escobar bought or intimidated anyone who might stand in his way, ruthlessly eliminating everyone from rival traffickers to policemen, judges, and politicians. His ruthlessness reached the point of no return in 1989, with the bombing of the Avianca plane with 100 passengers onboard to murder presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán.

A controversial ‘Robin Hood’

Yet, Pablo Escobar is not just a criminal. In fact, in the poorest areas of Colombia, his name is also associated with social initiatives.

Escobar invested enormous amounts of money in projects, making him popular among the most disadvantaged. He built houses for the poor, schools, hospitals, and soccer fields. In the ‘Barrio Escobar,’ one of the poorest areas of Medellín, he became a benefactor, offering houses and jobs.

These actions, which many considered a sign of altruism, allowed him to earn his people’s respect and a kind of social protection. Many see him as a hero fighting against the system’s injustice, interpreting his war against the Colombian government and the United States as a struggle for social justice. A ‘modern Robin Hood,’ attempting to lift his people while remaining a powerful drug lord.

The glorification of crime: the genius of evil

“In recent years, the media has investigated and mythologized Escobar’s figure. In particular, the TV series Narcos, produced by Netflix in 2015, highlighted his charisma and brutality. Escobar proved to be able to manipulate Colombian institutions with enormous sums of money, corrupting politicians and law enforcement to protect his drug trafficking empire. In exchange for his surrender, he managed to be imprisoned in his private prison, La Catedral, which he had built himself. La Catedral was more like a luxury compound, complete with amenities like a soccer field, bar, and waterfall. Although formally incarcerated, Escobar continued to operate the drug trade and maintain decisive influence over the country. When the government attempted to transfer him to a state prison to prevent his extradition, Escobar escaped, highlighting the weakness of the state and the extent of his control over institutions.

This type of representation has transformed a criminal figure into a symbol of rebellion, invincibility, and power. His ability to defy justice and build a global empire has fueled the glorification of crime and violence. Yet, behind this myth, there is a much more complex reality.

Criminal tourism and its contradictions

To this day, Escobar is not just a name associated with drug trafficking but has become a brand. Tourism related to Pablo Escobar in Colombia mainly focuses on Medellín. Among the main attractions are La Catedral, his tomb in the Medellín cemetery, the family home, and Hacienda Nápoles, which has been turned into a theme park. There are maps of the neighborhoods that grew thanks to his donations, as well as those of enemies and politicians targeted by the boss and places connected to the battles with his rivals. Furthermore, for many merchants in Medellín, selling Pablo Escobar souvenirs is a crucial economic source, especially in a context of poverty.

Items such as t-shirts and mugs attract tourists, offering an income opportunity in a country still marked by economic and social difficulties. While some see this phenomenon as a historical rediscovery, others view it as a commercialization of a painful past. Thus, the debate revolves around those who want to remember a bloody chapter and those who seek to turn the page, risking the glorification of the myth at the expense of reality. This debate was recently seen with the film Emilia Pérez, which tells the story of a fictional Mexican cartel boss in the form of a musical. Despite being nominated for numerous awards, Jacques Audiard‘s film attracted criticism from some Mexican audiences for treating a dramatic chapter of their country’s history with “too much lightness.”

The paradox of the myth of Pablo Escobar

Similarly, Pablo Escobar’s figure continues to divide public opinion. For some, he is a “hero” of the poor, while for others, he represents the symbol of evil. But what does all this mean for Colombia’s historical memory? How does it cope with its dark past? Today, the media glorification of the Patrón and the tourism linked to his landmarks complicate Colombia’s difficult task of coming to terms with its history.

The figure of Escobar illustrates how popular culture can transform crime into a commercial phenomenon, exploiting an enigmatic figure: a man capable of building a global criminal empire but also shaping contemporary culture.

In the summer of 2024, the Colombian Parliament began discussing a law that bans the sale of souvenirs related to Pablo Escobar and other drug traffickers. The proposal, supported by Congressman Cristian Avendaño, aims to protect the victims of drug trafficking and promote positive symbols. However, it has sparked protests among local merchants, who fear a negative impact on their tourism-related businesses.

The fascination of evil: crime tourism worldwide

The phenomenon of ‘crime tourism’ is not limited to Escobar: Al Capone in Chicago, death row tours in American prisons, and Jack the Ripper tours in London are examples of how places associated with the most famous crimes attract visitors. Even in Sicily, a strand of mafia tourism (or Anti-mafia tourism) has developed, creating a parallel with the tourism industry around Escobar. The Chernobyl disaster has generated another type of tourism, where people visit the ruins of Pripyat, a symbol of the nuclear catastrophe.

Works like The Godfather, Breaking Bad, and El Chapo fuel public fascination with crime by turning both fictional characters—like Walter White—and real-life figures—like Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán—into pop culture icons. These phenomena generate a debate about how crime is represented, blending entertainment and glorification.

On the one hand, there is the risk of romanticizing crime, overshadowing the suffering of the victims; on the other, if handled with respect, crime tourism could become an educational opportunity to reflect on the dark consequences of drug trafficking. The real challenge is finding the right balance—avoiding sensationalism while striving to tell a story that teaches and prompts reflection.