Maus | Art Spiegelman's graphic analysis of war

Author

Year

In 1978 Art Spiegelman convinced his reluctant father, Vladek, to talk to him about his experience as a Polish Jew during the Second World War. What came out of it was a serial of comics about a life smashed up by the Holocaust. After nearly forty years, Spiegelman’s Maus confirms itself to be a postmodern analysis of Word War II.

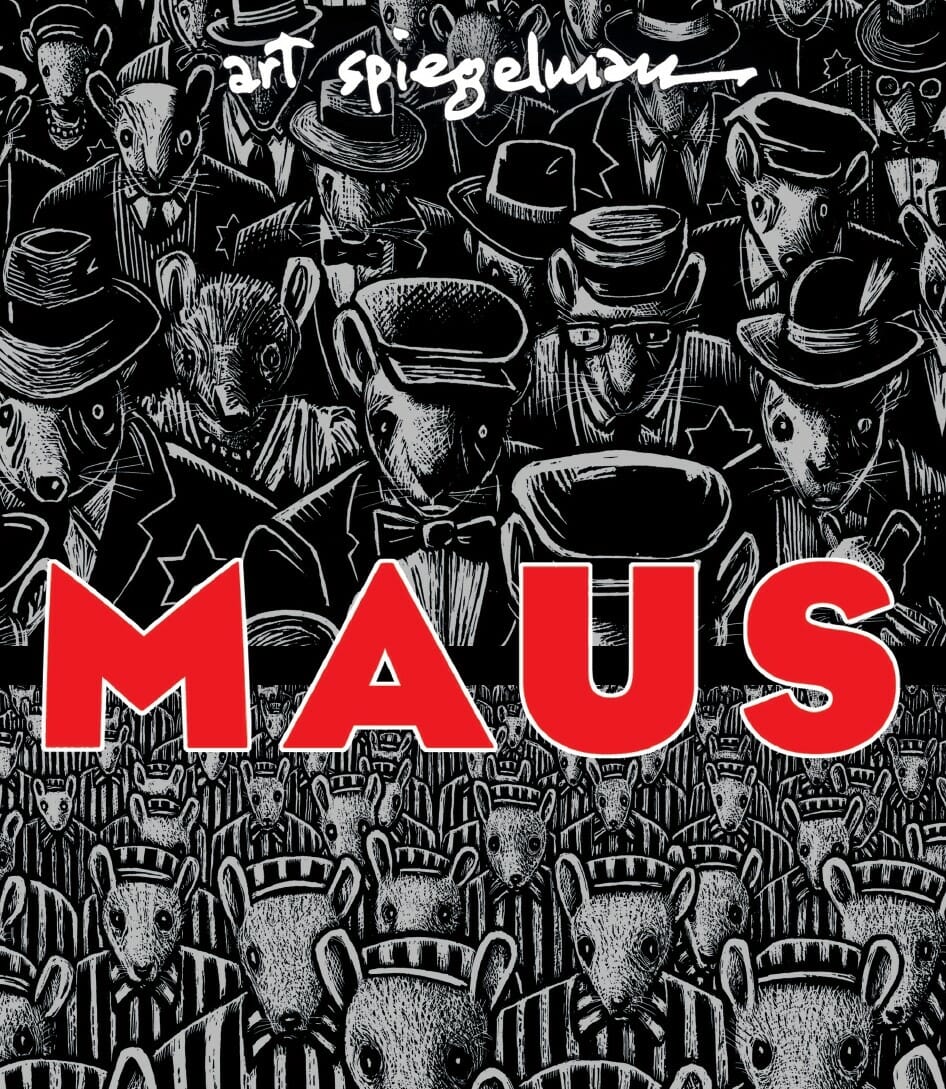

Later on, Pantheon Books published Maus in several volumes and then in a single-volume edition, but its first appearance was in December 1980. It was an insert in Raw, a magazine founded by Spiegelman himself and his wife Françoise Mouly in the same year. It was an influential magazine in the comics field and treated them as a cultural object worth disseminating and analyzing, and not just as entertainment.

Spiegelman’s Maus is the first and only graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize, in 1992. In 2011 the author made MetaMaus, a complete guide and detailed study of Maus, including contents such as an interview with Spiegelman, sketches, photographs and the original versions of Vladek’s recordings.

A survivor tale

The first panels, with Art visiting his father in New York, build a narrative frame leading the narration. The main focus remains on Vladek’s experience, while the framing allows the reader to understand Art’s point of view. The storyline swings in and out of the two timelines, giving a genuine view of Spiegelman’s family. The narration of the past represents a discovery of the author’s background, but it also allows him to develop his relationship with his father. It’s the story of the survivor Vladek and of the son Art discovering his family origins.

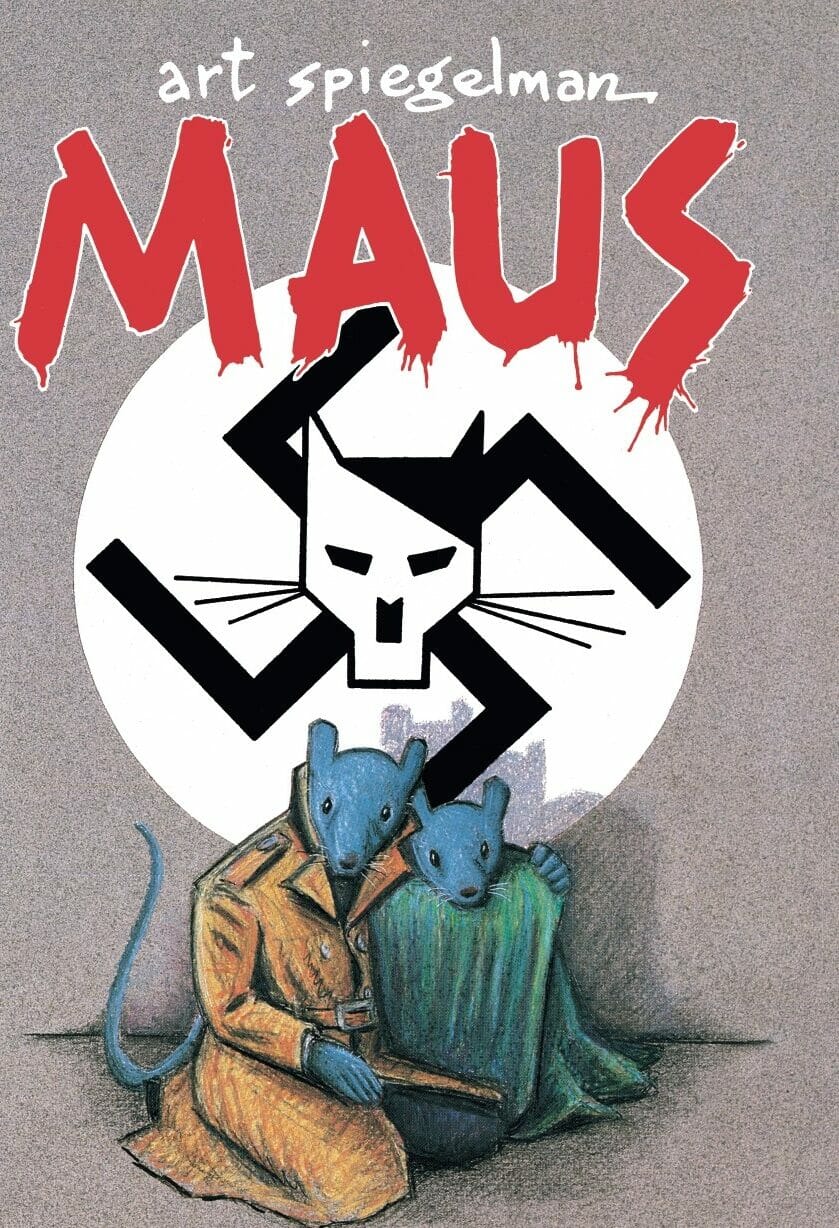

In the first part, Vladek speaks about his marriage with Art’s mother, Anja, in 1937. The Nazis invaded Poland shortly after and sent him to a work camp. On his release, life for Jewish people became more and more difficult. In 1943, the Nazis arrested Vladek and Anja and deported them to Auschwitz.

The second part starts with a jump in time to 1986, while Art is experiencing writer’s block. He can only move on when he has to host his father. At that time, he had the chance to know what his father never told him. Namely, what he went through during the months in Auschwitz and Dachau. Vladek tells his story in a detached manner, from his sufferings to the end of the war, when he could finally find his wife and start a new life. The last panel shows Vladek and Anja’s gravestone: he died in 1982 before the comics were finished.

The author leaves out hyperbole, judgments or personal comments. Describing what happened is enough. Every narrative and graphic of Spiegelman’s choice is oriented to make Maus an analysis of war as a complex and dark period, where everything was uncertain and nothing safe.

An hybrid language from the melting pot

Maus uses a specific linguistic style. The language Spiegelman’s father speaks is the outcome of the USA’s melting pot. Jews living in New York developed a unique way of speaking: a hybrid language that can be heard in some Woody Allen movies, just as in The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. Vladek’s English follows Polish grammar structures and contains words coming from Yiddish (spoken by Jews in the east of Europe). Some Yiddish terms became part of everyday American English, such as “bagel” or “meshugga“; they create a language that contributes to cultural identification.

Vladek’s speech is confident in flashbacks, while it gets uncertain in the present, reflecting the distance from his home country. Since he had to leave, he feels his nation betrayed him. He doesn’t belong to Poland anymore, nor to the USA, where he feels like a stranger. So, his language reflects his sensation of estrangement in the present time. The language becomes a metaphor for his long journey to find a safe place without forgetting where he comes from. The title itself is a pun: “maus” means “mouse” in German, but it also recalls the German verb “mauscheln” which means “speaking like a Jew“.

Spoken language is not the only element of postmodern art and literature in the comics. The frame scheme represents a solid meta-narrative element, given how it follows on from seeing how the comics develop in the author’s mind. The author blurs the line between present and past. Interruption in dialogues and jumps between the timelines make clear the chaos in his mind while listening to the story.

Spiegelman’s drawings as an analysis of the war

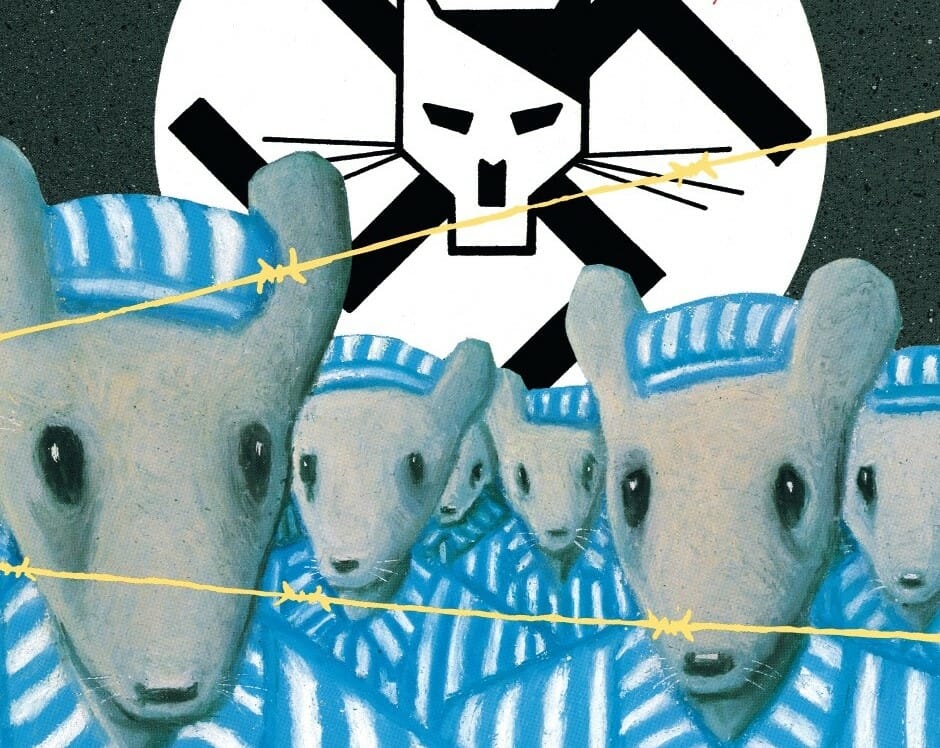

Spiegelman chooses various animals as metaphors of nationality. He represents Jews as mice, Germans as cats, Americans as dogs, Poles as pigs and French as frogs. Characters pretending to belong to other countries visibly wear a mask. The use of anthropomorphized animals in comics is nothing new in itself: both in children’s comics as Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse, and in underground comics for adults such as Robert Crumb’s Fritz the Cat. But those were just anthropomorphic animals, recalling the fairy tale tradition of beasts acting like humans. Spiegelman takes one step further, being the first illustrator using animals to show cultural differences. It’s the first device he uses to obtain emotional detachment, making identification difficult.

Spiegelman’s Maus is the first comic to talk about the Holocaust. Dealing with the concept and story of genocide, Spiegelman decided to let the story talk, putting himself in the background and showing more than telling. He eases as much as possible both the narrative and graphic style, growing apart from events. Page after page, panels are more and more neutral and stylized. Lines become rough and words seem screamed. The fragmented narration, dark sketches and a cold gaze on events create a historic reportage, that doesn’t even try to find an explanation or a sense, just expose. Matching history with its consequences in the present, Spiegelman’s Maus gives a strong and personal point of view on war.

Funding a genre

Maus was among the first book to be classified as a graphic novel, following the path was opened by Will Eisner (The Spirit, A Contract with God). It helped to strengthen the idea that comics can address several targets and discuss grown-up, serious subjects. Spiegelman wanted to create a more mature and underground style. Taking inspiration from Harold Grey (Little Orphan Annie) and Frans Masereel (The City), he contributed to comics’ recognition as artforms and not just entertainment, in opposition with superheroes’ comics.

Together with two DC Comics stories (Watchmen and The Dark Knights Returns), Maus contributed to changing the general perception of the comics. From that moment on, also thanks to independent publishers and a growing market, the comics industry was no longer dominated by Marvel and DC Comics and started to be something that could address not only kids, but also a vast audience of mature readers.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic