On Body and Soul | The disability to expose oneself

Year

Runtime

Director

Writer

Cinematographer

Production Designer

Music by

Country

Format

Genre

Subgenre

Is it possible that two people meet in their dreams?

Mária, On Body and Soul

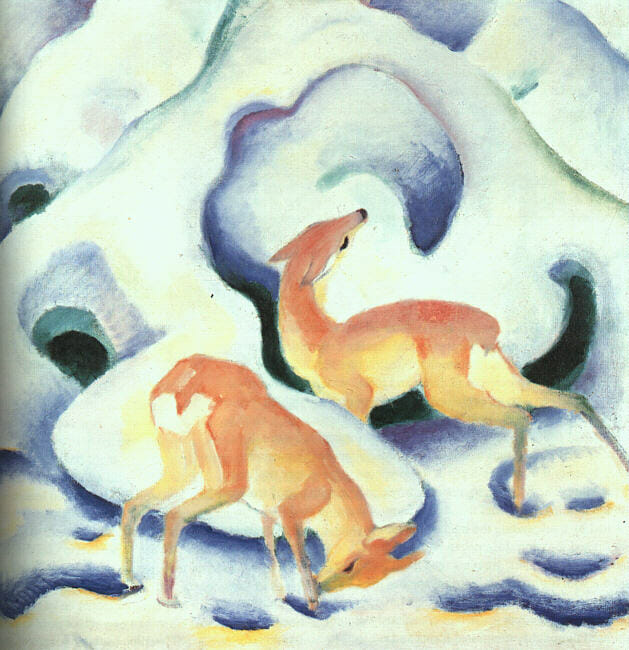

Meeting in dreams, in the guise of a deer, seems easier than meeting in real life. Where personal fears and social constraints prevent humans from following their true desires. On Body and Soul, by Hungarian director and screenwriter Ildikó Enyedi, shows this with tender brutality. His story revolves around two people who, although very different, struggle in a similar way with the social environment of the slaughterhouse where they both work. The two find peace and comfort only when they meet in their dreams. Like two deers, they run through the snowy woods, taking care of each other and enjoying their natural freedom. Forgetting their physical and emotional distress.

Budapest suburbs. Endre (Géza Morcsányi) is a middle-aged man who works as CFO in a large industrial slaughterhouse. Mária (Alexandra Borbély) is the new, very strict quality inspector. After a theft, the slaughterhouse is put under investigation and all its workers must undergo a personality test to identify the culprit. From the interviews, it turns out that Endre and Mária are connected on an oneiric level. Indeed, for some time now the two have been meeting in their dreams in the guise of deer. After a brief reluctance, they accept the chance to explore and get to know each other. They long for intimacy and agree to become vulnerable in real life, where everything is much harder than in dreams.

The answer to Mária’s question is an oneiric, at times cruel yet always humorous, glimpse into an (un)usual love story. Two people, despite their disabilities, try to get closer. At the beginning of the movie, the fact that Endre has a paralyzed arm and that Mária suffers from Asperger syndrome seem to be substantial obstacles to their intimacy. However, at some point both things become irrelevant. What is more, their disabilities are allegories of a common human condition: the disability to expose one’s soul.

Old story, modern contrast

Strong contrasts, perceivable with almost every sense, weave one of the oldest stories in the world: the Bible’s Song of Songs. Two people desire each other. Then they are afraid to approach one another. Finally, they seal their union as unique. The natural environment where the deer live versus the industrial building where Mária and Endre work, the silence of the forest versus the loud metallic sounds of the slaughterhouse, the freedom of the deer versus the constriction of the cattle, the pastel colors of the clothing and the interiors versus the intense red of blood. All of these are recurring elements in On Body and Soul that won the Golden Bear and the FIPRESCI Prize at the 67th Berlin International Film Festival in 2017. In addition, it was also selected as Hungary’s entry for Best Foreign Language Film at the 90th Academy Awards.

Sympathy for the animal

Right from the first few minutes, the viewer has to deal with blood: that of freshly slaughtered cows. Despite the rawness, everything seems normal and routine. Indeed, Ildikó Enyedi decided to film the daily activity of a slaughterhouse for ten days to document the cruelty to which cows are forced. She aimed to confront the viewer with this normalized and controlled violence, which she believes also affects human beings.

I have sympathy for all sort of animals. […] In some moment of my life, I felt pushed around, hustled, and not taken into consideration, like some cattle during their very limited life… in limited space and with limited social interaction. What they are living through is extremely cruel and I think it should stop.

Ildikó Enyedi, In Conversation with Ildikó Enyedi

Besides the animalistic appeal, Enyedi also wants to draw the viewer’s attention to the absence of freedom in human life. Mária and Endre are like the cows they work with: forced to live in certain roles by the system they are part of. In their dreams, however, they break free of it, returning to an ancestral form of life. They follow their instincts and physical desires as animals do.

Through the body to the soul

The essay-like title On Body and Soul recalls a theological work from the Middle Ages, a time when humans were still considered the only animals with a soul. However, this title fits perfectly with Mária’s personal search for her soul, which she pursues by experimenting with the potentials and limits of her body. The whole movie seems to proceed by thesis and antithesis to the discovery of Mária’s soul which, awakened by her encounter with Endre, now seems even capable of falling in love.

Listening to romantic music like Laura Marling‘s What He Wrote, watching porn, experiencing contact with a cow at work and with a stuffed puma at home. These are some of the challenges Mária undertakes to open up her soul. And when she decides to reach the next level of physical intensity she might experience, it feels natural. However, as soon as it becomes clear that Mária’s action is triggered by Endre’s rejection, it takes on a different dimension for the viewer.

And so probably, during the screening of On Body and Soul at the 2017 Berlinale, a few people in the audience fainted during a scene in which Mária bleeds profusely. As opposed to when cows were being slaughtered. Hence, it was not the sight of pure blood that shooked the viewer. Instead, it was more the realization that that blood came from a suffering person trying to overcome the disability of exposing her own soul.

Tag

Buy a ☕ for Hypercritic